The EGL Awards statuette, the Saga, as designed by artists Colin Poole and Kristine Poole. Graphic adapted from denvercomiccon.com. The first-ever Excellence in Graphic Literature Awards were awarded about a week ago, on Saturday night, June 16, at the Denver Comic Con. Here are the winners:

This is a strong slate of books. I’m particularly pleased to see Thi Bui’s The Best We Could Do win the Mosaic Award. I confess, though, that my choices for Adult Book and Book of the Year would have been emphatically different. When the EGL Awards first announced their short list, I expressed some reservations about the list, in particular the Book of the Year category, and I continue to feel that way. In some ways the EGL Awards have gotten off to strong start. They are tied to Denver Comic Con and its sponsoring nonprofit, the Pop Culture Classroom, whose new Director of Education, Dr. Katie Monnin, is a sharp and tireless advocate for comics as children’s reading. Katie and I were Eisner Award judges together in 2013, and her knowledge of and enthusiasm for comics left a vivid impression. Moreover, the EGL Awards appeal specially to K-12 educators and librarians, which, as Heidi MacDonald’s Publishers Weekly article of May 25 reminds us, have become some of the most important constituencies in US comics culture (and reportedly there’s a good deal of comics activity happening right this moment at the ALA Annual Conference in New Orleans).

However, I remained concerned about the makeup of the EGL juries. Though the Awards boast of judges who are “diverse, experienced and informed professionals that span the publishing, library, and education industries,” I see very few comics artists or professional comics critics among them. I do see wisdom in targeting librarians and educators, but I worry about awards that seek to represent the best in comics without reckoning on the larger comics community. Perhaps there cannot be one award that truly represents the fragmented and factious world of comics; I note that Eisner Award results tend to skew toward what is popular in the direct market, i.e. the comic shop culture. The EGLs might be seen as a corrective to that. But I really do believe that the EGLs would benefit from bringing in more creators—not just publishing professionals, but artists and writers—to create a more rounded judging culture. That said, I look forward to what the EGLs do next year. They are just getting started, and I hope for the best.

0 Comments

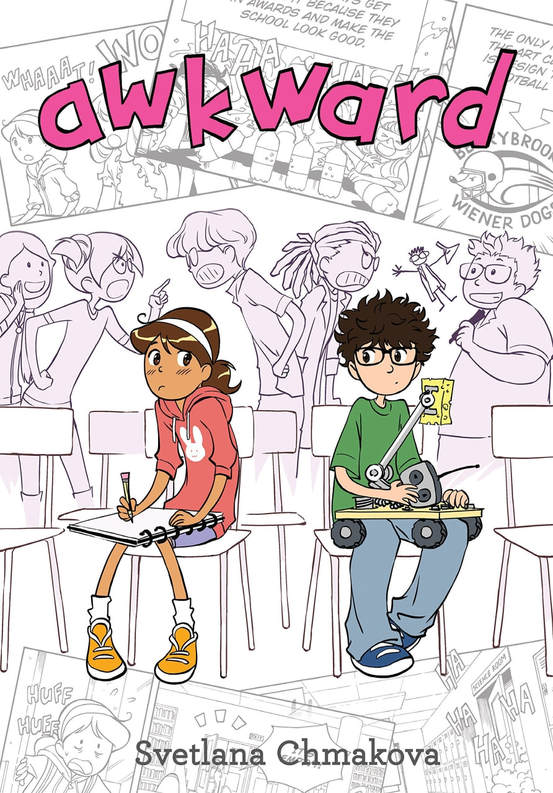

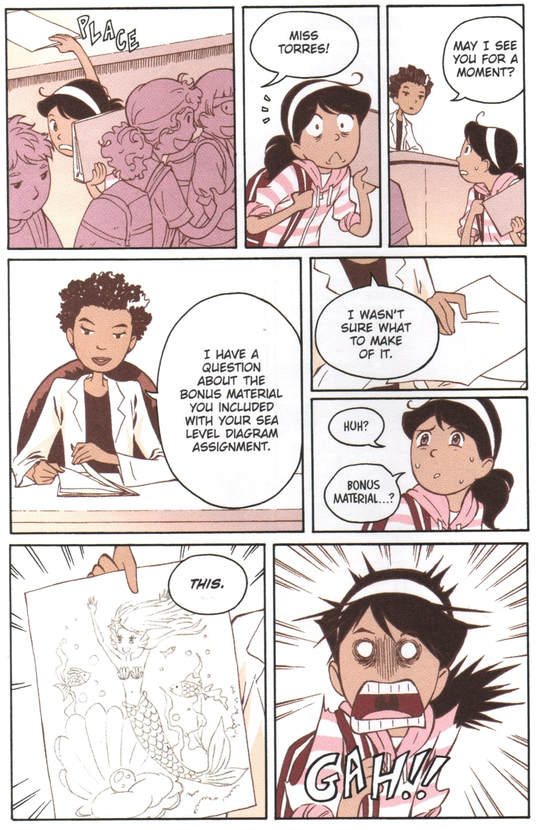

Awkward. By Svetlana Chmakova. Yen Press, 2015. ISBN 978-0316381307. 224 pages, $11.00. I missed this one when it came out in 2015, and missed its sequel, Brave, when it dropped in spring 2017—so I have some catching up to do. Awkward, now the first book in the growing Berrybrook Middle School series, is a middle-grade graphic novel about warring school cliques: art nerds versus science nerds. More particularly, it’s about the (of course) awkward relationship between Peppi, an art girl, and Jaime, a science boy, a relationship that promises to bridge the divide between those two competing nerddoms. The book cannily targets its intended age group with comically overwrought depictions of social anxiety, tentative friendships, and rivalries that seem epic to those involved even though they might seem minor to anyone else. It’s an eager, infectious riff on school life manga, from a cartoonist, Svetlana Chmakova, who prior to Awkward had specialized in OEL manga, with a fairly long list of titles from Yen (Nightschool, Witch & Wizard) and TOKYOPOP (Dramacon). Like Vera Brosgol, Chmakova is a Russian immigré with an animation background, but her career path has been different. She has described herself as a “manga author,” and Awkward takes a very manga-like pleasure in the absurdities of school life. Yet her manga influences now seem to be retreating, or quieting down, in favor of a Raina Telgemeier-like aesthetic of clarity and containment. Granted, shōjo manga still looms large in Chmakova’s style, which favors outsize expressions and exaggerated, super-deformed bursts of feeling—but she damps down the manga influence here by working through a gridlike page-and-panel aesthetic that follows the reigning style of US children’s graphic novels. Bleeds and diagonals are few, progress tends to be more horizontal than vertical, most pages are tidily contained within a white frame, and the effects lettering is fairly subtle and contained (with one terrific exception that you can find for yourself). In other words, Awkward, even as it leans hard on strong feelings and comic timing, dials down the manga elements and the intensity, instead aiming for a studied clarity. We are definitely in Raina territory here (Brosgol’s latest, Be Prepared, also goes there). Like much school life manga, Awkward stitches together the everyday and the outrageous, with cartoonishly exaggerated teachers, a shadowy, unseen principal who seems to hold the power of life and death, and petty disputes that flare up into high drama. The premise of art versus science, and the inevitable realization that the two can go together (cue the da Vinci), are not very fresh, and in general Awkward makes mountains of molehills, inflating minor screwups into soul-wrenching dilemmas. Further, we learn little about the protagonist Peppi’s home life or tics, apart from her love of drawing and her desire to stay as quiet and invisible at her new school as she possibly can. Scenes outside of school are set up to show Peppi the unexpected depths of her schoolmates; she herself doesn’t seem to have any. Awkward is not a very complex story, and Peppi’s eventual move from diffidence to action is foreordained. The character who exhibits the most depth—a go-getter classmate whose infectious, take-charge enthusiasm hides a troubled home life—gives the story a welcome dose of gravitas, but then disappears altogether. Her fate remains a dangling loose end as Chmakova rushes to the denouement. Awkward, then, is not a story that bears much critical thinking. However, it is delightfully rendered, and its unpredictable mix of comic hyperbole and genuine angst makes me want to read the sequels. Berrybrook Middle has the potential to be a great fictional school and story engine, and Chmakova, working at the crossroads of multiple traditions, has found a distinct style and energy of her own. Time for me to go read Brave.

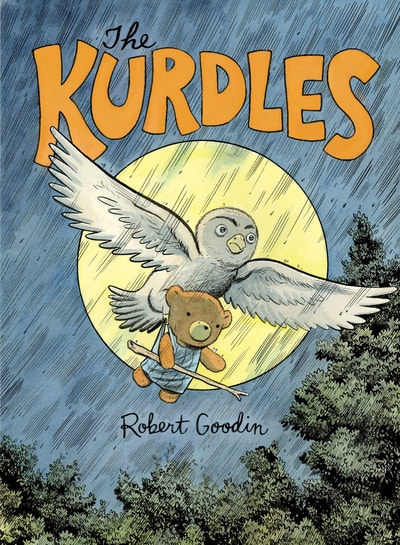

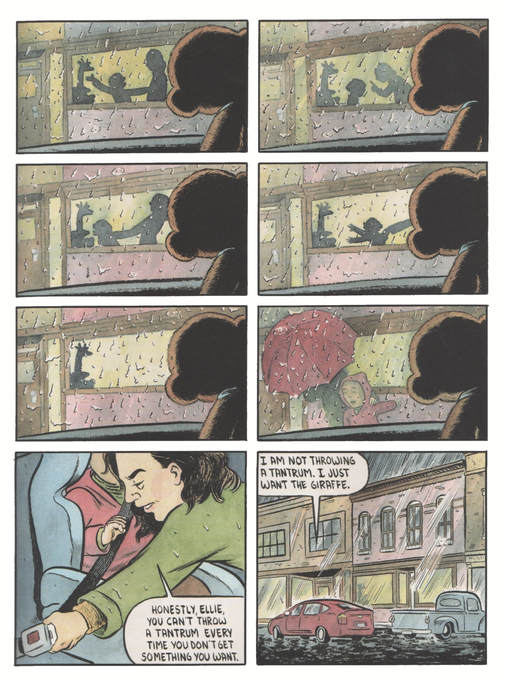

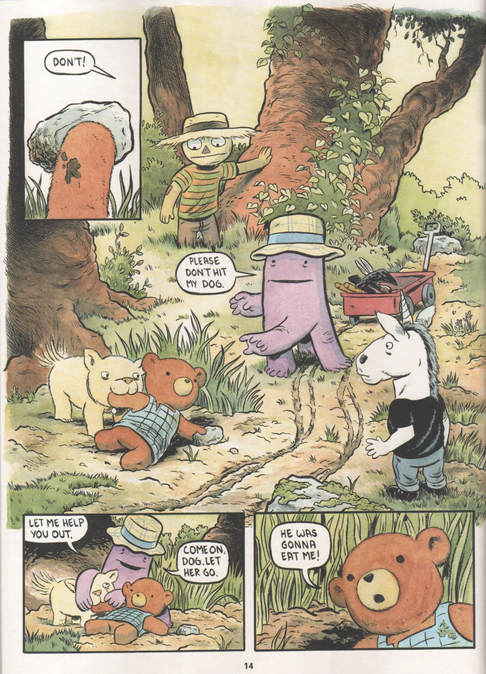

The Kurdles. By Robert Goodin. Fantagraphics, 2015. ISBN 978-1606998328. Hardcover, 60 pages, $24.99. A teddy bear gets lost, or discarded, by a child—that's how The Kurdles begins. Will she, Sally Bear, be reunited with "her" child"? The plot feints in that direction: a common story problem for child-centered, toys-come-to-life tales. Think Toy Story, and the nostalgia those films invoke: they're all about a kidcentric microcosm in which toys, though sentient, depend on the love of a child to give their life meaning. But The Kurdles doesn't end up telling that kind of story; instead it pulls a narrative bait-and-switch and becomes a sort of anti-Toy Story, one in which no Andy or Christopher Robin is needed to confer life or purpose on the lost teddy. Sally finds herself in Kurdleton, a woodland retreat, in the company of other critters: a land-going pentapus (think octopus with just five limbs), a unicorn in a tee shirt and jeans, and a scarecrow that evokes Baum's Oz (with perhaps a touch of Johnny Gruelle's Raggedy Andy too). This klatch of strange beasts also recalls, for me, Tove Jansson's Moominland, or Enid Blyton's Faraway Tree series. There's that same sense of utopian, slightly anarchic domestic community, of a little world apart from our own with its own matter-of-fact logic (or no governing logic at all). This is home to The Kurdles, and where the story wants to stay. With The Kurdles, then, cartoonist Robert Goodin has fashioned a fantasy world that owes a great deal to the history of children's books. Oddly, though, the book seems out of step with almost anyone's idea of a children's graphic novel today. The Kurdles does kids' comics the way, say, Gilbert Hernandez and co. did with Measles (1998-2001), or the way Jordan Crane did with The Clouds Above (2005)—that is, eccentrically, with seemingly no regard for the conventional wisdom about what today's children need or want. I suspect that's part of the reason why I like The Kurdles so much. Certainly I like this kind of idiosyncratic world-building in comics, regardless of intended audience. I expect that The Kurdles' best audience will be comics-lovers with a feel for the medium's history and an appetite for the upending of traditional story motifs. Me, I like it for the quirks and for the way it refuses to make sense. The book's opening depicts an argument between a human mother and child, as seen from a distance by a teddy bear. We don't yet know that the bear is Sally, or that she's alive: Sally's autonomous life is revealed only gradually, slyly, in the pages that follow, after she is parted from this human family. (The sequence in which she finally transitions from inert doll to living, moving creature is so delicious that I'm not going to show it here.) It takes even longer to reveal Sally's capacity for speech—which we realize about the same time as her capacity for self-defense, even violent resistance. What brings Sally fully to life is her arrival in Kurdleton, and the appearance of Kurdleton's other bizarre residents: What follows is a shaggy dog story in which a sickly house (the sum total of living quarters in Kurdleton) becomes anthropomorphic and then, as if delirious with flu, begins to sing sea shanties as if it were a drunken sailor. Yes, you read that right. The other denizens of Kurdleton set out to find a cure, but I'll say no more. Suffice to say that the Kurdles have no origin stories, no explanations for why they live in this place, nor any backstory that anyone feels obliged to ask about. Only Sally, of all the characters, has the rudiments of an "arc" (and even hers gets rerouted). What's more, the Kurdles don't have the familial structure of Jansson's Moomins, or the love of a human child, à la Milne's critters in the Hundred Acre Wood, to bring them together. They're just weird, and live in a weird place, where their essential weirdness needs no excuse. That's The Kurdles. The Kurdles is also eccentric visually. Lushly drawn and watercolored, it's organic, i.e. emphatically pre-digital, in look, with a fully realized, woodsy environment. Boldly brushed contours coexist with dense hatching, and the art is texture-mad. Color-wise, Goodin's pages depart from the Photoshop norm of most children's graphic books, and I found myself looking for the rough edges where linework and watercolor met (though Goodin is so crisp that I hardly ever found them). The work is old-fashioned and sumptuous, illustrative and humanly accessible to these middle-age eyes. Far from the clear-line, flat-color style so redolent of children's comics (the bright Colorforms look that bridges everything from Hergé to Gene Yang), The Kurdles is beautifully scruffy, or scruffily beautiful. It's as if Goodin, whose work I know mainly from TV animation and his erstwhile Robot Publishing venture, is determined to make The Kurdles a space of retreat from all of his other doings. The Kurdles is blithe, blunt, and unsentimental, sometimes startling, often deadpan-hilarious: a world and logic unto itself. I dig it. I do worry, though, about the commercial prospects for work like this, i.e. work that carries with it a wealth of history and memory but hails from outside of the children's publishing mainstream. This is the sort of work that has flourished fitfully here and there under the aegis of the direct market and within a small-press, underground aesthetic (I think for example of Neil the Horse, c. 1983-88, by Katherine Collins, formerly Arn Saba). Fantagraphics has announced a Kurdles Adventure Magazine for this summer, and reading more Kurdles would do me good, so I can only hope. This is too weird and wonderful a world to lie fallow. Fantagraphics provided a review copy of this book.

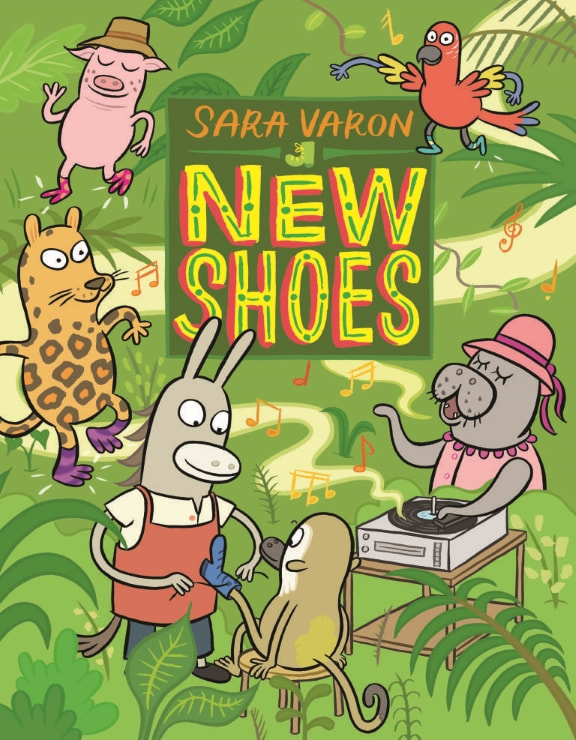

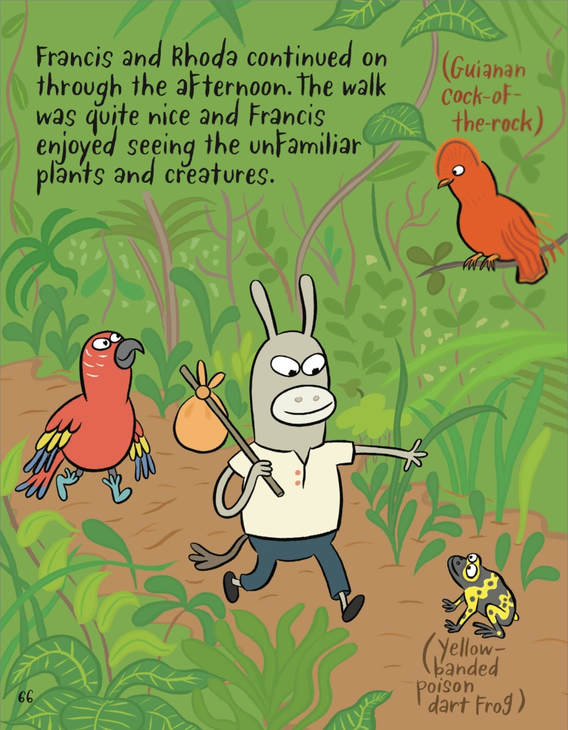

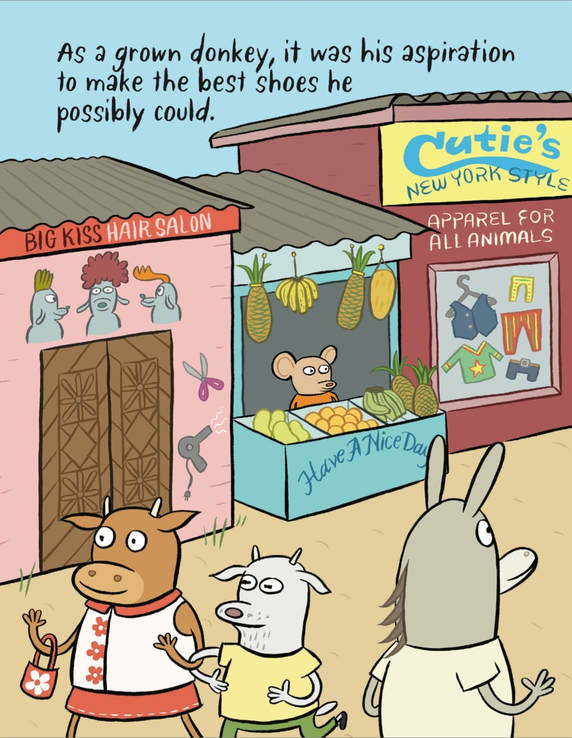

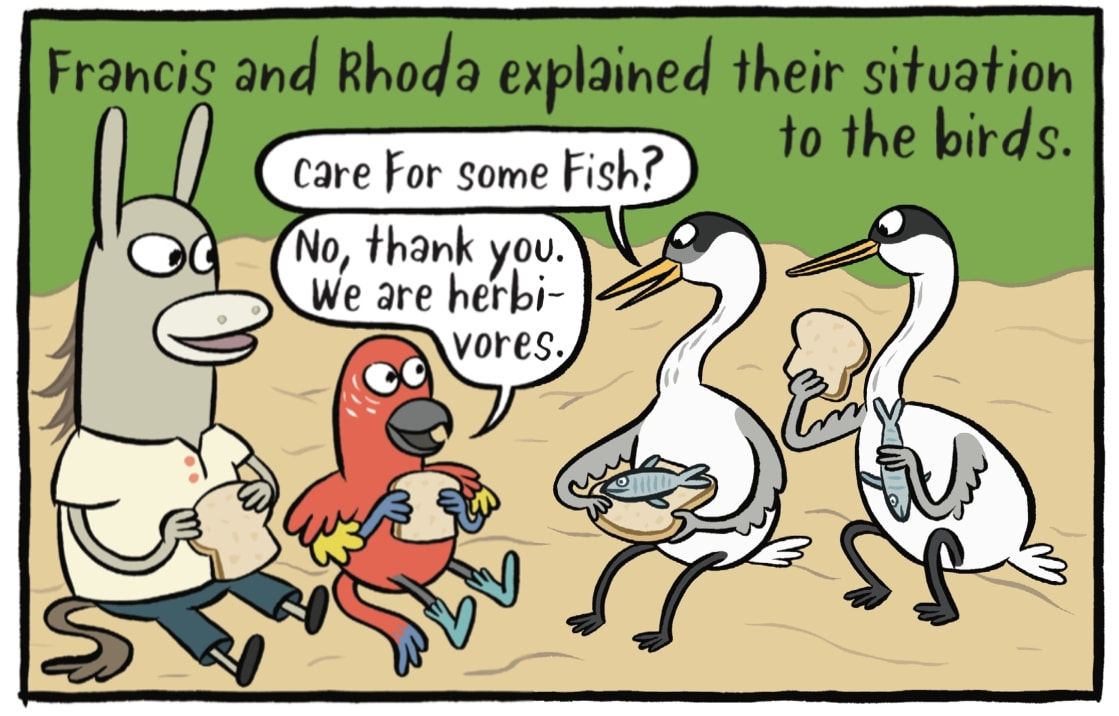

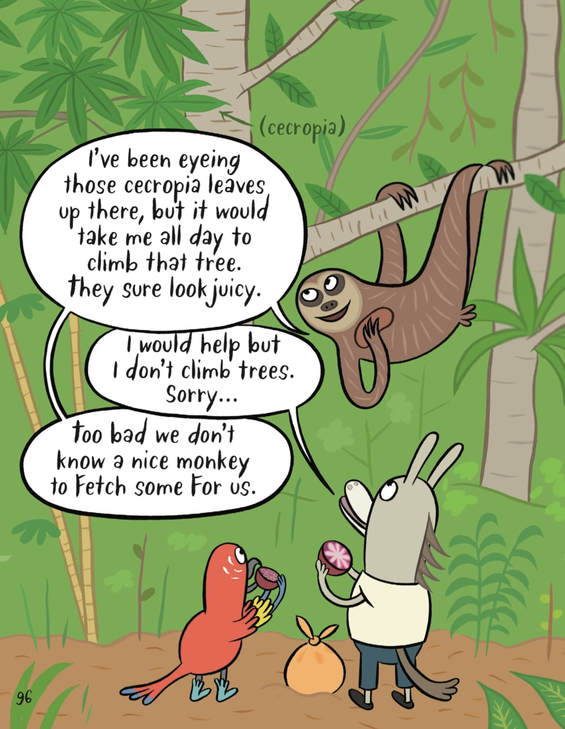

New Shoes. By Sara Varon. First Second Books, March 2018. Hardcover, 208 pages. ISBN 978-1596439207. $17.99. Book design by Danielle Ceccolini and Sara Varon. New Shoes, a genial, unlikely fable, follows a cobbler named Francis who wants more than anything to make the perfect pair of shoes for his favorite singer, a pop star who is coming to his town. To that end, he hopes to enlist his traveling friend, Nigel, to secure the needed supplies—but Nigel, it turns out, is missing. So Francis, aided by another friend, Rhoda, embarks on a quest to get the supplies himself (and find Nigel). The thing is, Francis is a donkey, Nigel is a squirrel monkey, Rhoda is a macaw, and the singer, Miss Manatee, is just that. New Shoes is an animal fable—and not in the purely metaphorical sense of, say, Spiegelman’s Maus, in which human characters wear mask-like animal faces. No, these animals are meant to be animals, even though they’re anthromorphized. Francis, despite wearing clothes and shoes, is emphatically a donkey. Rhoda is a bird (she flies). And so on. In this world, varied animalness is the point. Once again, Sara Varon (Bake Sale, Robot Dreams, Chicken and Cat, Sweaterweather, etc.) has created a funny animal comic that is, yes, funny, but more than that. New Shoes takes place in a tropical world inspired by Guyana. Francis and Rhoda’s quest entails journeying into “the jungle,” i.e. equatorial rainforest, and the book lovingly details Guyanese flora and fauna. Varon gives labels for myriad critters: black curassow, golden-handed tamarin, three-toed sloth, and so on. Ditto for plants: cecropia, philodendron, bromeliad. In other words, the book packs in a lot of zoological and botanical information. More than that, New Shoes implicitly reflects Guyanese culture: an Anglophone Caribbean mix with a complex colonial history and diverse population. Signs in Francis’s village are in English, village buildings are small, colorful, and individual, and Varon’s myriad animal types may stand in, allegorically, for Guyana’s mingling of East Indian, African, Amerindian, and other peoples. Miss Manatee, “the River Queen,” is a calypso singer, and listening to calypso on phonograph records seems to be a cultural constant (record players are an important prop throughout). Varon’s version of Guyana is perhaps utopian but based on direct experience: her husband, John Douglas, former boxer and Olympian (1996), is from Guyana, and her visits there, specifically to the town of Linden, seem to have shaped if not inspired the whole book. The specific cultural and geographical influences of Guyana make New Shoes stand out among Varon’s animal tales—and the characters’ varied animalness implicitly celebrates Guyanese diversity. Thus New Shoes espouses cooperation and harmony-in-difference without dealing explicitly with race, ethnicity, or postcoloniality. This charming fable rests on a complex, if largely implied, cultural foundation. I was struck by the book’s depiction of labor and economy. Even as it extols friendship and community, New Shoes focuses on acts of exchange: goods for goods, goods for work, and work for work. Yet money plays no role; barter and trade are everything. Rhoda agrees to help Francis on his quest in return for a pair of shoes. Francis offers bread to passing herons, who in return counsel him to seek help from some capybara. Later, Francis trades bread to the capybara and some river otters in return for swimming lessons and advice. Later still, he settles a debt with Harriet, a jaguar, by offering her his guidebook to rainforest animals, and then the two make a further exchange: some of Harriet’s plants, and advice on how to take care of them, in return for a pair of Francis’s shoes. While the book also depicts acts of spontaneous, uncompensated kindness—say, a neighbor helping a neighbor—much of its action involves establishing reciprocity and trust through barter. Tellingly, these exchanges are not merely economic but also build goodwill and community. If some characters seem altruistic, others, by contrast, appear self-interested—yet all of them come together civilly through the act of trading. What’s more, the worst offense in the book turns out to be thievery, when a character decides to take something for nothing rather than making an honest trade. Varon’s utopia, then, is not without practical considerations of trade and work, but couches those in terms of communal ethos rather than capital. New Shoes could spark some fascinating exchanges with young readers about use value, exchange value, and perhaps even alternatives to commodity capitalism! Varon’s work has a distinctive charm. Her stories, as New Shoes amply demonstrates, tend to be about not only moving the plot forward but also taking an interest in the world, imparting information about geography, culture, or beloved pastimes. They represent the work and the pleasure of learning. At the same time, Varon uses animals and other “nonhuman” characters to convey feelings of friendship, love, and loss (most piercingly, I think, in her breakthrough book Robot Dreams). Along the way, she scatters moments of droll, deadpan humor: Varon's telltale graphic style is very readable. Her character designs are distinct and unmistakable; every character looks different from every other one (and I can see some influences she has cited, including Jay Ward and William Steig). The figures are clean and shadowless, yet outlined by robust brush-inking. Her bright, unshaded pages boast discrete forms and solid, eye-popping colors, yet also a complex mixing of hues (as in the varied shades of green that make up New Shoes’s rainforest). Inked on Bristol board but then colored in Photoshop (as is Varon's SOP), New Shoes happily blends old-school and digital methods, combining springy linework with subtle coloring. Layout-wise, Varon alternates between framed and unframed images, favoring big, open spreads and full bleeds. Often, single images take up a page or spread; alternately, Varon may go for a page of two or three (or, very rarely, four) panels. Clarity and momentum are all, and New Shoes fairly carries the reader along. Sara Varon has become one of First Second’s signature authors. I had the privilege of interviewing her, back in 2009, at the International Comic Arts Forum in Chicago, and it has been a pleasure to see more and more of her work—work that explores friendship and community for the benefit of young and old readers alike. New Shoes charmed me right off, but keeps growing in my estimation as I think about it—another delightful, subtle, low-key triumph. First Second provided a review copy of this book.

|

Archives

June 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed