|

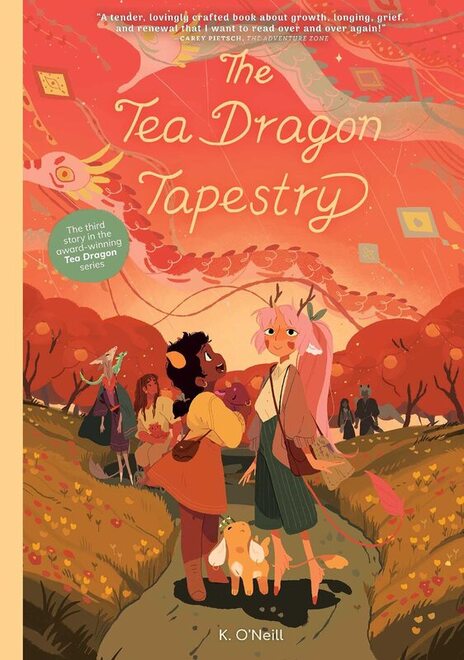

The Tea Dragon Tapestry. By K. (Kay) O’Neill. Oni Press, ISBN 978-1620107744 (hardcover), 2021. US$21.99. 128 pages. For weeks, my family and I have been playing the Tea Dragon Society game Autumn Harvest, based on Kay O’Neill’s comics series (the first two books of which I’ve reviewed here, and here). I’ve won a few games and lost many. I enjoy the game; it’s happy and challenging and graced with beautiful graphics by O’Neill. The gameplay feels very much in tune with the ethos of the comics. In all this time, til now, I have not thought to read the third and final volume of the comics, The Tea Dragon Tapestry. I don’t know why. Maybe I just wasn’t ready for another dose of O’Neill’s gentle and affirming storytelling, another spell in the tea dragons’ idyllic fantasy world. The past year has been bruising, and I am tired. Or maybe I feared reading through it and having to leave it behind, too quickly. I’m glad to have read it, now. Tapestry is the most mournful, but then the most joyous, of the three books—the one that feels most like a healing for genuine hurt. As usual, the challenges and conflicts are conveyed with a tender, whispering lightness; O’Neill doesn’t push too hard. As usual, the mood is that of a communitarian, vaguely anticapitalistic pastoral: a utopia of cute and mystic creatures, some humanoid, some not, living, giving, and crafting in a spirit of contemplative harmony. You know, I really am sad to have to leave this world behind—fortunately, a book can always be reopened. O’Neill’s tea dragons (in fact, small, catlike creatures whose bodies grow tea leaves) live symbiotically with people in an unforced arrangement that exemplifies commensalism and loving attachment. O’Neill’s humans (in fact, a range of anthropomorphic characters, such as fauns and centaurs) serve as caregivers to the dragons, as well as crafters, each devoted to a specific discipline that benefits their village community and the larger world. Scenes of brewing and drinking tea punctuate the stories, evoking an unhurried life defined by discreet rituals and communal care. In Tapestry, one of the tea dragons, Ginseng, mourns the loss of her previous caregiver, while Ginseng’s current caregiver, Greta, struggles to figure out how to help her. Meanwhile, Greta’s friend Minette, uprooted from what she thought her life was going to be, mourns the life she used to have while trying to commit to and find joy in the way she lives now. At the same time, Kleitos, a peripatetic blacksmith, considers taking Greta on as an apprentice (again the emphasis on crafting) but mourns the fact that he has lost the joy that smithing once brought him. O’Neill’s major characters all suffer from dislocation or loss, and each is quietly bereft in their own way, but they cope with these feelings in the context of a loving, sustaining community. As ever, O’Neill’s storytelling is empathetic, understated, and rooted in everyday routines rather than bombastic and action-filled. And, as ever, the drawing is gorgeous: O’Neill renders their characters and settings without containing contour lines, as blocks of color. The colors are solid, not painterly, but often mixed with such subtlety that it helps to read the book under a bright light. O’Neill’s cartooning is sweet and elegant rather than rowdy or assertive, dedicated to form rather than line. The net effect is like that of a Miyazaki-esque ecofantasy art-directed by Mary Blair. Works for me—I have to admit, I love looking at these pages. When I reviewed the previous books in the series, I was rather too grumpy, complaining that their subdued, gentle approach made genuine high-stakes conflict impossible—that the books were too Edenic, too idealized, and unwilling to deal with the tough stuff. I recant those remarks! The conflicts are there; you just have to lean in close and look and listen carefully. The gentleness is intentional, but there is a critical intelligence at work too; the world conjured in these books offers ways to envision a better world of our own. The Tea Dragon series is a remarkable thing. I gather O’Neill has finished with the series, and I can only say, damn, that’s a shame—I’d love to spend more time in this bucolic yet urgently humane story-world. The game helps.

0 Comments

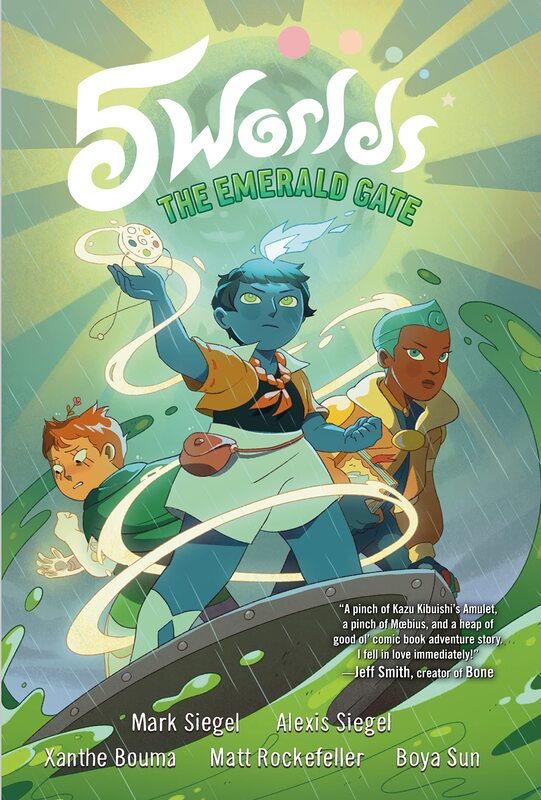

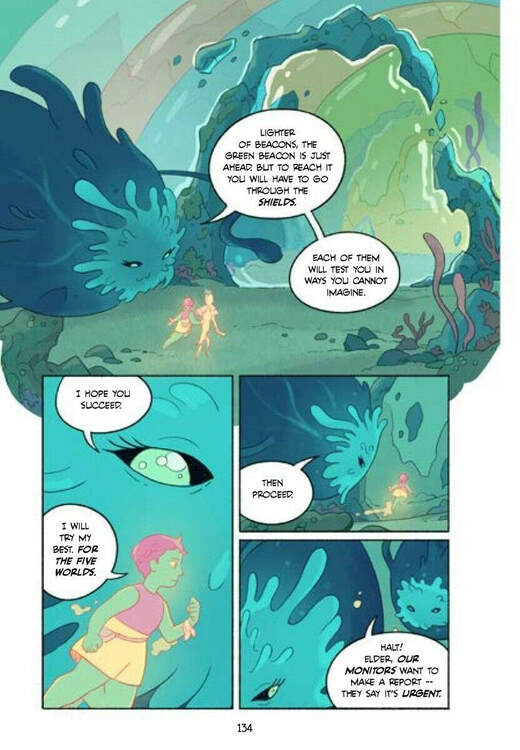

5 Worlds: The Emerald Gate. By Mark Siegel, Alexis Siegel, Xanthe Bouma, Matt Rockefeller, and Boya Sun. RH Graphic/Random House, 2021. The 5 Worlds series (five books set on five planets, published over roughly five years) has always been a high-wire act, balancing space fantasy, ecofiction, and Miyazaki-esque tropes with allegorical broadsides against neoliberalism and right-wing populism—all of this served up by a complex collaborative team consisting of five geographically dispersed co-creators. The way they have all worked together is a bit of a miracle. I’ve reviewed every volume (one, two, three, four) and keenly followed the evolving story of heroes Oona, An Tzu, and Jax and the many co-revolutionaries and loved ones they’ve gathered along the way. The series reaches it big finish with The Emerald Gate, and it’s a corker of a climax. Overall, the series has proved smart, bold, and very good—though I must admit it has left me with a sort of gnawing dissatisfaction, somehow. Pointedly allegorical from end to end, 5 Worlds has targeted egotism, greed, environmental carelessness, demagoguery, and (most clearly in Book 5) gradualism and hidebound deference to tradition, as its youthful heroes throw off the shackles of what has been done in favor of what can be done. The story is unabashedly progressive, topical, and on the nose. The Emerald Gate, dedicated to “the young people not waiting for permission to bring long overdue change to our world,” casts lead heroine Oona as a Greta Thunberg-like climate activist who must defy authority and take big risks to make big changes. The Five Worlds of the title are suffering a gradual ecocide—that is, dying of heat death—but an oily Trumpian oligarch (possessed by an ancient dark force) is trying his damnedest to smother that fact. Only drastic measures can save the day. This final volume’s signature phrase, Green doesn’t wait for permission to grow, signals Oona’s shift from diffidence to absolute certainty; she is done questioning, and now knows the way. Though the book takes time to sow little seeds of doubt (What if Oona’s plan only plays into the villain’s plan? What if the perfect solution turns out to be perfectly disastrous?), there really is no doubt: Oona and her fellow heroes must do something radical, must play for the highest stakes, if they are to save the Five Worlds. They must rebel. Oona must rebel. Above all, she must embody moral and political certitude. The Emerald Gate, more than its four predecessors, reveals an odd tension: between the radically egalitarian and democratic spirit to which the series aspires, and, on the other hand, the near-deification of Oona, the fated heroine who must give her all for the cause. In the home stretch, Oona undergoes a sort of ritual testing, running a gauntlet of five “filters” or “shields,” that is, moral and psychological trials, so that she can recognize “the truth.” Through this ritual, Oona rejects tradition and hierarchy, factionalism and rage, egocentrism, and personal desire. In effect, she rejects the novel’s version of neoliberalism. But this renunciation is the key to her final apotheosis; even as she rejects crude individualism, she is affirmed as The One who can channel the virtues and energies of all Five Worlds. While every member of Oona’s team plays a vital part in the novel’s ending, their final success depends on deferring to Oona’s vision and artistry (“Do not tell me your plan. I trust you”). In this way, the story uneasily mixes the political and the mythic—and remains, perhaps in spite of itself, a heroic fantasy in awe of individual gifts, somewhat at odds with its collectivist ethos. What makes all this work is that there is a price to pay. I won’t get into the details; suffice to say that Oona’s apotheosis entails a change of state and a goodbye—though also a sort of opening into ineffable new possibilities. Her transformations are so dramatic that she cannot return to ordinary life. Nor can she be quite understood. To resolve the story, Oona must escape the containment of the story, must step outside the frame her friends (and we readers) understand. Channeling the powers of the Five Worlds means being more than a person, and so there is lovely sense of consequence to the ending. What I’m talking about is not quite the wounded bittersweetness of Frodo Baggins at the end of The Lord of the Rings, but at least something that surprised me and made me reread the last few pages with care. The Emerald Gate well and truly finishes the story of Oona that began in 2017 with The Sand Dancer. I look forward to rereading this series all at one go. Aesthetically, it’s remarkably cohesive, a seamless collaboration despite the complex interworking it so clearly required. The Emerald Gate is (as I’ve come to expect) a sumptuous feast of worldbuilding and of deft, surehanded cartooning. The payoff in the end is rousing and full of feeling, enough to knock me for a loop. Overall, the book comes across as a paean to the indomitable spirit and visionary energy of the young—though this is one of those texts that, in my Children’s Literature classes, we’d be cross-examining to see what its construction of youth says about the hopes and needs of adults. While 5 Worlds depicts young people as radically free, it follows a didactic agenda that tries to teach young readers to be those free spirits, and to save us all. Ultimately, it rejects the shaded, tragically complex vision of one its avowed inspirations, Miyazaki, in favor of an unequivocal ending in which hesitation and gradualism can be identified with a hated Dark Lord and summarily banished. It’s all about the certainty of Truth. Yet the skeptic in me wants something a shade more tangled and complicated. In the end, I found myself wondering if the utopianism of 5 Worlds conflicts with some of the messages it has been trying so hard to convey. But, oh, what a rapturous five-year ride.

|

Archives

June 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed