|

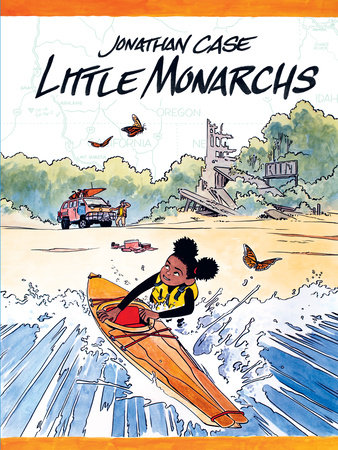

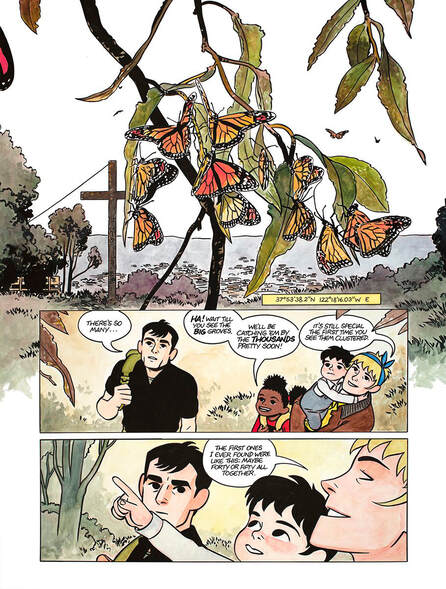

Little Monarchs. By Jonathan Case. Holiday House/Margaret Ferguson Books , ISBN 9780823442607 , 2022. US$22.99. 256 pages. A Junior Library Guild Gold Standard Selection. This post comes belatedly and is not much more than a mash note. A few days ago, I called the Eisner Award-nominated Little Monarchs, by Jonathan Case, "an extraordinary piece of worldmaking, ... dense, involving, subtle, and beautiful." I stand by that. It is one of the best graphic books for readers of any age I've read in a while (and I've been reading a lot of good ones lately, now that school is out). I dove into Little Monarchs hurriedly, without doing my usual obsessive reading of paratexts, indicia, and so on (I'm usually a bit compulsive about how I crack open books that are new to me). I had the book out from my local branch of LAPL and was bingeing before casting my annual Eisner votes, so I was rushing. I hadn't even read the jacket copy. So, it wasn't until I finished the first of the book's dozen chapters that I began to realize that the story was set in a world I did not quite recognize, or a changed version of our world where something had gone wrong (I overlooked a detail given on the first page: that the date is 2101). In fact, Little Monarchs is a post-apocalyptic survival story, though officially a middle-grade (ages 8-12) sort of book. In it, a ten-year-old girl, Elvie, and her guardian, a forty-something biologist named Flora, drive through a drastically depopulated North America in which most people dwell underground, unable to travel safely in sunlight. Elvie and Flora mostly avoid encounters with these "deepers," preferring to go it alone. They dread attacks by "marauders," that is, scavengers who would pirate their stuff.  So, the world of Little Monarchs is different. In it, about fifty years have passed since a "sun shift" has killed off most mammal life. Prolonged exposure to direct sunlight (more than a few minutes) can be fatal. Most human survivors are socked away in underground bunkers, and only a few crepuscular or nocturnal mammals, such as bats, can hope to survive. Flora and Elvie are able to live topside because Flora has developed a medicine that keeps them safe from "sun sickness" for up to about a day and a half at a time. The medicine derives from the milkweed within monarch butterflies, so Flora and Elvie follow the yearly path of the monarchs' migration, catching butterflies, harvesting scales from their wings, releasing them, and creating ever more batches of meds. At the same time, Flora seeks a more permanent solution in the form of a heritable vaccine. Little Monarchs, then, is the story of an never-ending road trip and a scientific quest. Remarkably, this survival story reads less like horror and more like an adventure. That has everything to do with the character of Elvie, a Black girl who is resourceful, eagle-eyed, courageous, decent, and funny. Elvie explores and improvises and above all uses her head. She can face down her fears and make do when disaster strikes. The heart of Little Monsters is the bond between Elvie and Flora, her White caregiver, who is something like a mom, big sister, tutor, and friend all at once, and whose quirks Elvie knows and forgives. You can believe that these two understand and love each other. The book gains heft from Elvie's journal entries: expository interludes that serve to orient the reader while showing off her smarts. These entries combine Elvie's home-school assignments (given by Flora), drawings, reflections, and tips. Elvie knows how to live in the wild world Jonathan Case has imagined, and her entries impart a great deal of knowledge. Case has mapped her story onto real locations, using real geographic coordinates, and included a wealth of fascinating detail about everything from knot tying to the monarchs' life cycle. The story-world fits this girl to a tee, and vice versa. Little Monarchs takes interesting risks. As a survivalist story in a broken world, it delves into the hard ethical questions that such scenarios tend to pose: What are you willing to do to survive? Do the ethical constraints of civil society apply when the world has been upended? Must you be willing to hurt others to protect yourself? The story kicks into gear when Elvie finds another, much younger child wandering in the sunlight and has to take him in, which leads to Elvie and Flora nervously weighing the risks of involvement with other people. At first, Flora seems somewhat mistrustful, even phobic, about taking that risk, but, as things turn out, she has good reason to be. There are reversals, betrayals, and shocks in the story. The last act depicts hard things — and Elvie has to do some hard things, too. Little Monarchs isn't The Road, of course (RIP to the brilliant Cormac McCarthy), but does ask its readers to weigh questions of ethics and risk in the face of grave danger. Somehow it does this and remains a thrilling adventure and credible middle-grade story about a plucky ten-year-old kid. And the visual artistry of it! Little Monarchs is a feast of lovely images made by hand, from the lettering to the gorgeous watercolors. Reading it against a backdrop of other recent graphic novels for young readers, even good ones, I was reminded of how seldom I get to see work at this scale that is handcrafted even down to its finest details. Case is a terrific comics artist, designing dynamic pages, drawing believable characters and environments, pacing and punctuating riveting sequences of high-stakes action as well as quiet scenes of discovery, and making every detail count. As I said a few days ago, he cartoons with an economy and grace that recall Alex Toth as well as latter-day classicists who have drunk from the same well: Jaime Hernandez, R. Kikuo Johnson, and Chris Samnee. His character designs, breakdowns, staging, and layouts are equal to his terrific writing. Little Monarchs urges engagement with the natural world and offers readers all sorts of potential adventures off the page as well as on. You could take this book on the road with you and learn a lot. More than anything, it is a classic quest story, pulled off with warmth, wit, and bravery, surprising and gutsy right up to its very last page. After reading so many well-intended moral and political fables for children in which messages are reliably delivered and conclusions are just what one would expect, I took delight in its splendid eccentricity. Highest recommendation!

0 Comments

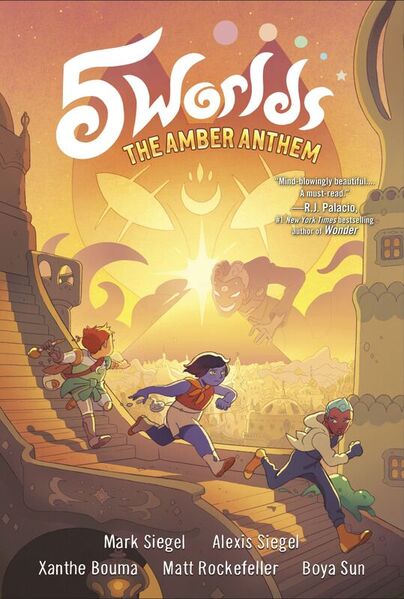

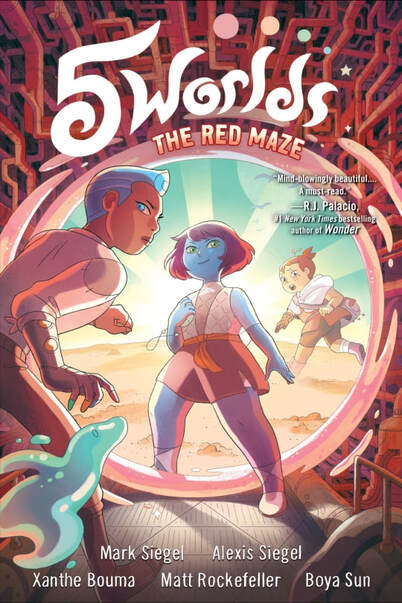

About eight weeks ago, I announced that KinderComics would be “taking a roughly six week-long break.” Every time I say something like that, I sigh—and sigh again when, eventually, tardily, KinderComics returns. So, okay, here I go again: Scheduling pressures under COVID, the endlessness of preparation and grading in my online teaching, and a looming sense that the world is going wrong, that it could explode any day—these things have been getting in my way. I admit I often consider closing this blog and moving on. Only reading and writing pleasure draws me back. So, let me switch gears and get down to the stuff that matters: 5 Worlds: The Red Maze. By Mark Siegel, Alexis Siegel, Xanthe Bouma, Matt Rockefeller, and Boya Sun. Random House, May 2020 Paperback: ISBN 978-0593120569, $12.99. Hardcover: ISBN 978-0593120552, $20.99. 240 pages. Who is the author of Five Worlds? This sprawling adventure series is the work of what seems to be an impossibly harmonious five-person team; somehow, the results comes across as the work of a single hand. Aesthetically, the series is gorgeous, a real feat of cartooning. Structurally, it’s tricky, with a modular, five-book shape, each book color-coded and focusing on a different world and different puzzle to solve (or secret to uncover, or McGuffin to find). Politically, it’s timely, with ever more obvious allegorical broadsides against Trumpism, neoliberalism, and xenophobia; in this progressive fantasy, world-building goes hand in hand with topical commentary that feels, as I’ve said before, on the nose. Alongside its familiar genre elements—the hype invokes Star Wars and Avatar: The Last Airbender as comparisons, but Miyazaki hovers over the whole thing too—Five Worlds conjures the anxieties of our times, and scores palpable hits against “fake news,” noxious right-wing media, climate change denial, and the shamelessness of greed-as-doctrine. KinderComics readers will know that I’ve been fairly obsessed with this series, reviewing Volumes One, Two, and Three in turn, and that I found the third, 2019’s The Red Maze, the most successful thus far at balancing genre convention, fresh discovery, and political relevance. With the latest volume, The Amber Anthem, the series has reached its fourth and penultimate act, and appears to be barreling toward a big finish. It’s actually a bit of a blur. In The Amber Anthem, the McGuffin is a song—the anthem of the title—and the story’s climax depends on thousands of voices lifted in song together, in a vision of peaceful yet powerful resistance that suggests real-world analogies: the Movement for Black Lives, and the recent surge in street protests despite COVID. (The book must have been written and drawn before that surge, and before the pandemic too, but its spirit of protest makes such analogies irresistible.) Here the dominant color is yellow, and the world is Salassandra, a planet briefly glimpsed before but now the center of the action. Our heroes, Oona, An Tzu, and Jax Amboy, once again seek to relight a long-quenched “beacon” in order to save the Five Worlds from heat death and environmental collapse. The Trumpian villain, Stan Moon—a host for the dreaded force known only as The Mimic—redoubles his attacks, even as Oona, An Tzu, and Jax take turns in the spotlight. The plot, as usual, is complicated, a tangled quest. Ordinary Salassandrans alternately help and hinder that quest (many having been persuaded that our heroes’ mission means ruin for the “economy,” and so on). The climax depends upon bringing together people of “five races.” Jax, a sports star, joined by a beloved pop singer, uses his celebrity to draw those people together—a handy metaphor for the way pop culture may provide opportunities for activism and community-building when official politics becomes hopelessly corrupt. Along the way, Anthem clears up several nagging mysteries, in particular the backstory of An Tzu (whose body has been, literally, fading away, book by book). I expected as much. Each new volume of Five World has delivered some big reveal or transformation for one of the heroes; now, with An Tzu’s history disclosed, the series seems poised for its finale. There’s a sense of unraveling complications here, yet of a tense windup at the same time. I confess that the big reveals here, though some of them came out of left field, didn’t leave me gaping or even happily stunned. Instead, I found myself jogging, not for the first time, to keep up with the frantic plot. Reveries and remembrances, sorties and missions, switchbacks and betrayals: it's a lot. The climax, though, is beatific: a shining vision of pluralism and collaboration and a lyrical evocation of “many strands…interweaving.” It's a triumphant close, but a corking good cliffhanger in the bargain, introducing a new moral dilemma and setting the stage what promises to be a breathless final volume. I’m keen—Five Worlds has been an annual stop for me, and I look forward to seeing how it all plays out. Five Worlds is a marvel of coordinated effort and cohesive design; again, its author-in-five-persons communicates like a single voice. Its world-building is lovely—I would happily pore through sketchbooks showing the collaborative process behind these books. That said, I’m starting to wonder whether the series’ complex rigging, breakneck plotting, and moral certainty are robbing it of some degree of complexity (as opposed to structural complicatedness, which it has in spades). The effect of Five Worlds on me, so far, has been like that of an action movie with soul, but its compression and momentum have not allowed for the sort of complex characterization that marks, say, Jeff Smith’s Bone, whose deepest characters, Rose Ben and Thorn, are sometimes at odds and go through hard changes. Five Worlds gestures toward the hard changes, and has enough soul to tend to the hearts and minds of its heroes, but everything feels a bit rushed. Despite the loveliness of the proceedings, then, at times the generic tropes come across as just that (Stan Moon, for example, speaks fluent Villain). When stories are ruthlessly streamlined, often what we remember are the clichés. I hope not. I look forward to the last chapter, The Emerald Gate, which I hope will bring everything—world-building, political urgency, and layered characterization—into balance one last, splendid time. When I open up the fifth and final volume, I’ll be holding my breath.

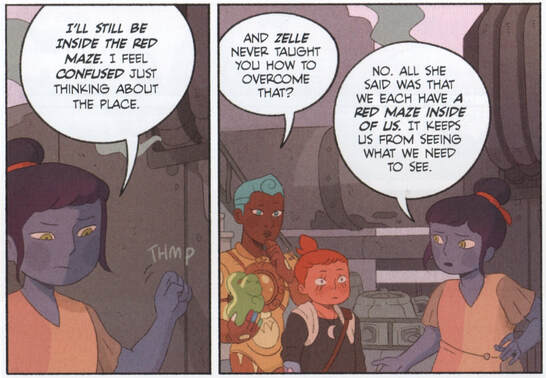

5 Worlds: The Red Maze. By Mark Siegel, Alexis Siegel, Xanthe Bouma, Matt Rockefeller, and Boya Sun. Random House, May 2019. Paperback: ISBN 978-1101935941, $12.99. Hardcover: ISBN 978-1101935927, $20.99. 256 pages. 5 Worlds — the epic science fantasy series by brothers Mark and Alexis Siegel and the artistic team of Xanthe Bouma, Matt Rockefeller, and Boya Sun — has been overstuffed with invented worlds, scenic wonders, and dizzying plot twists from the start (that being 2017’s The Sand Warrior and its 2018 followup, The Cobalt Prince). The series has bounded from one setup to another with a breathless energy and worked up a sprawling, spiraling plot. Its delights are many, but its confusions too, inspiring mixed reviews from yours truly (the first here, the second here). It’s a labor of love, obviously, and the complex collaboration behind it has wrought visually seamless results: a remarkable artistic and editorial feat. There have been times, though, when 5 Worlds has seemed to rush narratively from one thing to another: this world, and then that; a tip o’ the hat to this influence, then that one; another disclosure of tangled backstory, another "huh?" moment. I’ve sometimes wondered if the influences were going to cohere into something distinct, and if the long game wasn’t getting in the way of the individual volumes. But no longer. The recently-released third book, The Red Maze, gathers up, extends, and deepens 5 Worlds with confident character and thematic development, careful pacing, and a troubling relevance. It’s the strongest, most sure-handed of the three books to date, also the sharpest and most topical. An ambitious entry, it gains depth on rereading, while still pulling this reader eagerly on, toward the next volume. Now we’re talking. Briefly, 5 Worlds depicts a system of five planets (to be visited over the series’s five volumes) that are dying of heat death and can only be saved by the lighting of a series of ancient “Beacons,” one on each world. Each new volume of the series focuses on one of the worlds and uses an integrated color scheme implying the dominant culture(s) of that world. The protagonists, a classic heroic triad, are Oona, trained in the ancient discipline of “sand dancing,” who is tasked with reigniting the Beacons; An Tzu, a street urchin of unknown origins and powers, still coming into his own; and Jax, a sports star and (secretly) an android, though archly nicknamed “The Natural Boy.” Each has an unfolding origin story full of twists and surprises, from Oona’s true heritage (revealed in The Cobalt Prince) to the newfound humanity of the Pinocchio-like Jax (who was waylaid for most of the second book but returns and grows more complex here), to An Tzu’s “vanishing illness” (i.e. disappearing body parts) and newly discovered oracular powers. All three have nonstandard, stereotype-defying qualities and hail from vividly realized cultures (carefully imagined in terms of ethnicity and class). In The Red Maze, all three have arcs, problems, and discoveries, without any one of them being overshadowed by the others. From the book's opening, a frantic action scene that reintroduces Jax, to its final pages, which tease the forthcoming Volume Four, the plot rockets along, and yet, more so than in past volumes, makes room for quiet, character-building exchanges and epiphanies. The Red Maze made me want to reread all three volumes with an eye on that proverbial long game. If the second book improved on the first, this new volume overleaps them both. The Red Maze’s special power comes partly from its pointed political relevance. The book allegorizes the current politics of our world in a way that's pretty much on the nose, and crackles with urgency. At last, it seems that 5 Worlds is discovering (or perhaps I am just belatedly discovering?) its themes, which include, broadly speaking, fighting impending ecological disaster while speaking truth to power, and finding one’s identity in principled resistance without losing the joy of life. The Red Maze depicts its heroes saying "hell no" to the short-sightedness and greed of oligarchs and false populists who have vested interests in denying that anything is wrong. Along the way, of course, it tells multiple coming-of-age stories, as each of our three heroes has self-discoveries to make — but it's the constant backdrop of world-threatening climate change that sharpens everything and raises the stakes. This particular volume takes place on “the most technologically advanced of the Five Worlds,” the supposedly free and democratic Moon Yatta, against the background of, ah, an election campaign that pits the ordinary mendacity of a self-serving incumbent politician against the demonic scheming of a populist gazillionaire challenger, a demagogue boosted by authoritarian media and keen to exploit xenophobia. Both would like to silence our heroes’ message of looming environmental collapse. Basically, we’re dealing with climate change denial here, as well as a stew of political chicanery, nativism, and bigotry. Familiar? There’s more. The Yattan regime, we learn, suppresses a minority of protean “shapeshifters” who have the ability to change bodily form (and gender) but who are subdued by “form-lock” collars (clearly, signs of enslavement). Signs of oppression are everywhere, most obviously in a diverse crew of rebellious street kids who become an intriguing if perhaps under-developed new supporting cast. Despite the kids' help, though, our heroes' attempts to penetrate the industrial complex or “maze” around Moon Yatta’s Beacon come to nothing. So, desperate measures are called for. Jax, athletic superstar, is coopted to play in a much-hyped televised championship that becomes a propaganda coup for the challenger, supported by the obscenely wealthy “Stoak” brothers. And if all that doesn’t come through clearly enough, allegorically, consider this blurb on the book’s inside front cover: ...Moon Yatta is home to powerful corporations that have gradually gained economic control at home and on neighboring worlds... [Its] democratic system of government is widely admired in the Five Worlds, but there is increasing concern that it may be undermined by the political influence of its corporations. Indeed, a cabal of super-rich profiteers, aided by the rantings of a Limbaugh or Alex Jones-like media blowhard, works to undercut the Yattan democratic system. Everything, it seems, is about money, even health care: a hospital scene depicts a boastful, tech-savvy doctor determined to leech every penny from his patients. Other scenes show populist xenophobes towing the oligarchs’ line and condemning the shapeshifters for threatening the social order. Racism and homophobia are implicitly evoked (you have to read between the lines, but what’s there isn’t that hard to see). Unsympathetic readers might call this propaganda, but children's fiction, including fantasy fiction, has always been value-laden if not didactic. My description may make The Red Maze sound less like a story than a screed, but it actually is a story, and a thrilling one, a rattling good yarn. At its heart is a spiritual crisis for Oona: the weight of expectation on her is so great that it crushes her joy in dancing, in using her near-magical art. She falters, bewildered and panicked by the retreat of her powers. (This recalls, for me, Kiki’s temporary loss of confidence and magic in Miyazaki’s adaptation of Kiki’s Delivery Service.) Late in the book, a training sequence, that is, a mentor-mentee sequence, allows Oona — and the story — a calming and refocusing moment, a catching of breath. Thus Oona is able to take a perspective beyond that of the looming crisis, and learn a crucial new power. Her dilemma has to do with finding ways to sustain her spirit in the face of overwhelming environmental and political odds: how do you keep going when things are so terrible? That’s a kind of dilemma, and story, that needs telling right now. Oona's mentor Zelle (one of a long line of mentor or donor figures in 5 Worlds) tells her, “We each have our own red maze. We can be lost there.” What’s needed, Zelle suggests, is joy and inspiration: some delight in the doing, right now, whatever the odds against us. Oona, though, admits that she feels stuck “inside the red maze. I feel confused just thinking about the place.” She has to look for other perspectives on her task, other angles on the problem. Out of that crisis comes the through-line that gives The Red Maze its depth and integrity. This third volume of 5 Worlds makes everything click. It's aesthetically dazzling, of course; 5 Worlds has always been beautifully designed, rendered, and colored. The Red Maze is another master class in revved-up graphic storytelling, the pages at times bursting into frenzied action, during which bleeds, diagonals, and unframed figures spike the book's ordinarily measured and lucid delivery (dig, for instance, the ecstatic climax). The series has always been good at that sort of thing. Yet now 5 Worlds is jelling narratively and thematically. The Red Maze builds smartly on the previous books, and brings fresh nuances to its heroes, growing each into a deeper, more interesting character. The myriad artistic influences are still there, but the world-building no longer feels, say, stenciled from Miyazaki; instead the story-world has gained enough heft and momentum to draw this reader into its own singular orbit. And the stakes feel genuinely high. I expect that, when 5 Worlds is completed, rereading it all and watching it come together is going to be a very rewarding experience. Granted, The Red Maze won't make sense to those who haven't read the first two volumes: though 5 Worlds has a modular structure (one world per book), it is definitely one continuing story, not an episodic series. (Start with The Sand Warrior.) But this third volume is a terrific reward for those who've been following along: a timely, urgent, artfully layered adventure. I think we’re looking at some kind of monument in the making. Random House provided a review copy of this book.

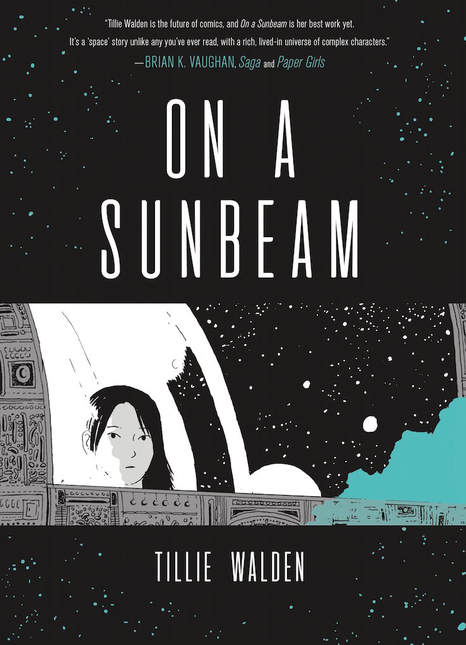

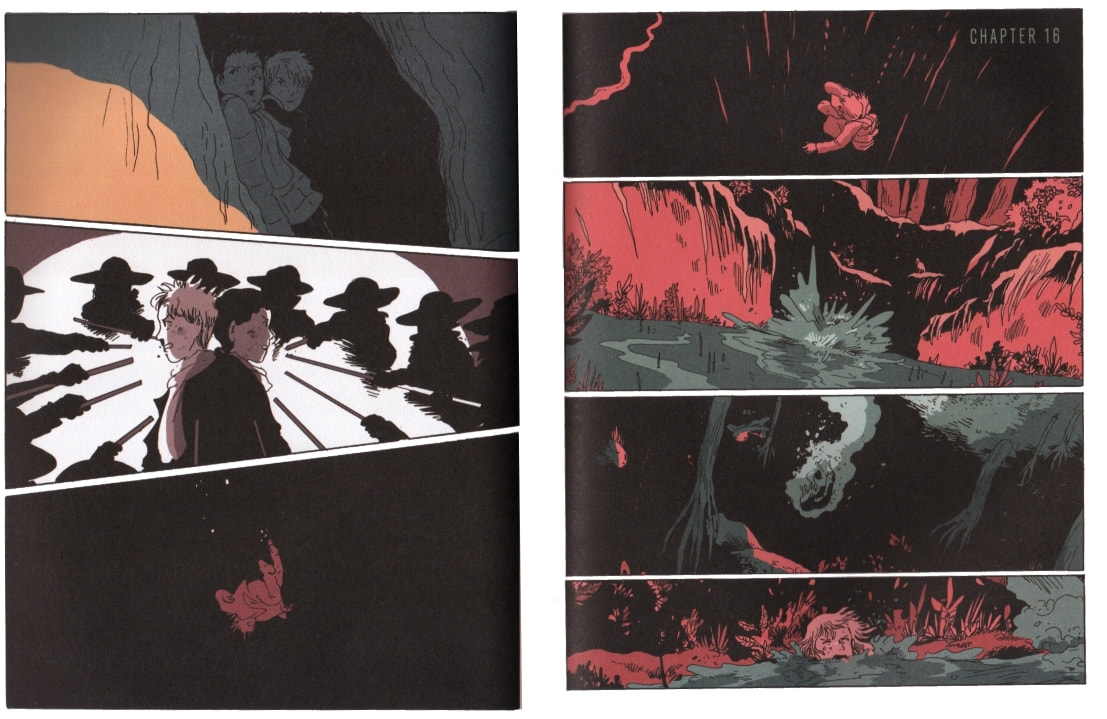

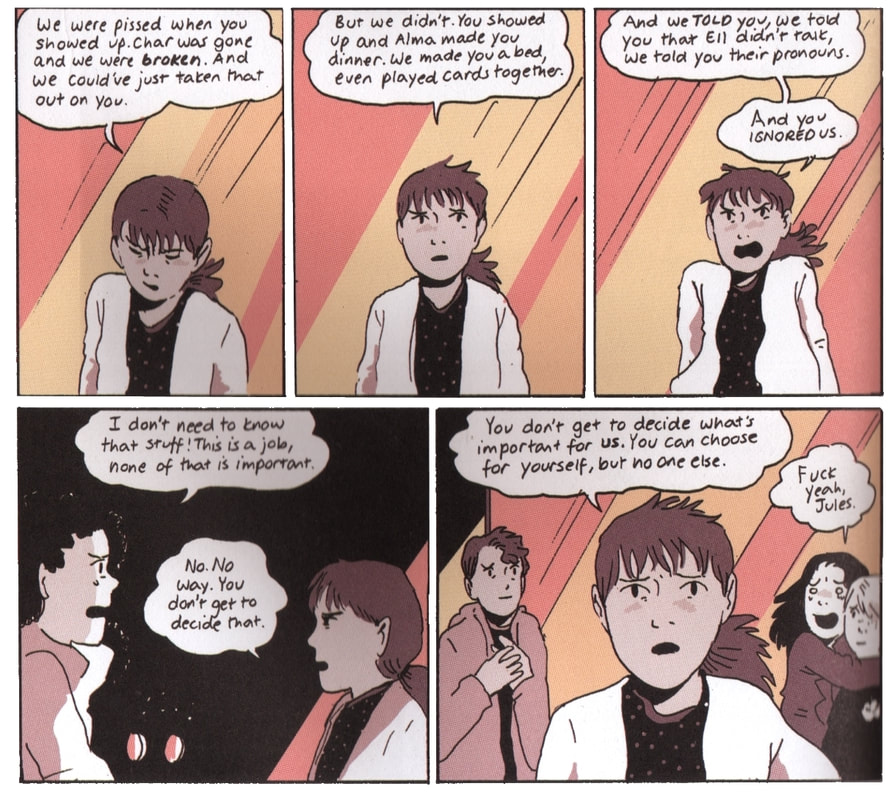

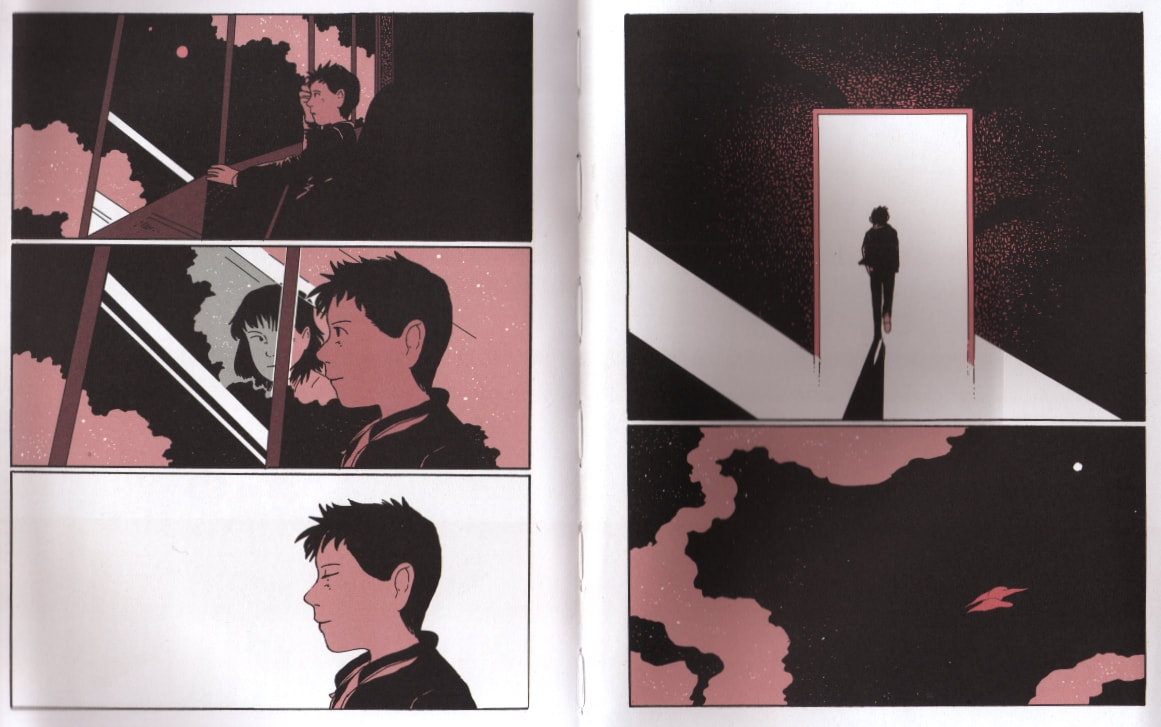

On a Sunbeam. By Tillie Walden. First Second, 2018. ISBN 978-1250178138. 544 pages, softcover, $21.99. Tillie Walden has an uncanny gift for, and dedication to, comics. Her newest book On a Sunbeam (compiling and adapting her 2016-2017 webcomic of the same name) is a gift in itself: a queer romance that starts as a young adult school story—an acute exploration of tenderness, social anxiety, and the keeping of secrets—but then blossoms into a breathless adventure tale. At the same time, it's a paean to queer community and found family, while also being, wow, a space opera. I'm not kidding. In other words, On a Sunbeam is a miracle of genre-splicing and of unchecked, visionary cartooning—one in which Walden does whatever she wants, while yet upholding a traditional, eminently readable form. As soon as I got a copy, I was pulled along, pretty much helpless, for an ecstatic 540-page ride. The story ought not to work, in theory. On a Sunbeam is galaxy-spanning science fantasy in an undated future, one governed less by grounded scientific extrapolation, more by poetic metaphor. The spaceships resemble fishes, swishing across the skies and through the cosmos on fins. Buildings float through space looking exactly like earthbound buildings: a church, say, or a schoolhouse. This is deliberate; Walden treats space like terrestrial geography, only bigger. Ditto architecture. Much of the action involves the repair of damaged or derelict buildings out in space, by a "reconstruction" team whose job falls somewhere between renovation and archaeology. They deal in statuary, stone, and tile as well as high tech. Often the settings don't feel like "space" at all—until they do. No one wears spacesuits, though everyone's bodies must somehow adjust to being in deep space. Oh, and the cast seems to consist solely of women and genderqueer characters. What sort of universe is this? To hell with what would work "in theory." The story, for its first 2/3 or so, shuttles back and forth between two main settings: an upper-crust boarding school (in space), and the Aktis (or Sunbeam), the reconstruction team's spaceship. But it also shuttles back in forth in time, across a gap of years: the "school story" part of the plot happens in flashback, five years past, while the story's "present" follows Mia, formerly of the boarding school, now a (green) member of the Aktis crew. Walden skillfully uses layout and coloring variations to set these two timelines apart (and ultimately to bring them together). What really ties these timelines together is the bond between Mia and her schoolmate Grace, a socially withdrawn girl of unknown origins. Grace and Mia share a romance that is tender and profound: a genuine love story. However, their bond breaks when Grace is mysteriously summoned home from school. Her home is an enigma. Mia longs to see Grace again, but the years go by and a reunion seems impossible. About midway through the book, though, Mia and her Aktis family undertake a fantastical quest for Grace's homeworld, tying the book's several plotlines together. The final third brings the Aktis (and us) to an otherworldly setting worthy of Jack Vance or Keiko Takemiya. On a Sunbeam has tremendous emotional and tonal range. The anxious school scenes of the first half capture budding relationships, first steps toward intimacy, and uneasy social maneuvering, resonating with Walden's great memoir Spinning. The bonding of Mia and Grace recalls, for me, the lyrical evocation of young and growing love in the book that introduced me to Walden, the dreamlike I Love This Part. Walden is great at conjuring the rivalries and vulnerabilities of young women in social groups, the tension between ringleaders and outliers, and the no-bullshit demeanor of girls among girls, at once strong and fragile. On a Sunbeam carefully builds the relationship of Mia and Grace, two believably different young women, into a deep, unqualified love; their unspoken understandings and gestures of mutual care and self-sacrifice make them a couple to root for (and the book, delightfully, suggests that queer romance is common in their school and world). Yet Mia's later initiation into the Aktis crew creates other deep relationships, both among the crew and between Mia and every other member. The tenderness of the Grace/Mia dyad suffuses everything that comes after, and what begins as a rough, contentious team gradually becomes, emphatically, a family, one of Mia's own choosing yet defined by complex bonds with and without her. The book's range broadens dramatically in its final third, as the plot upshifts with a vengeance: Walden leaps headlong into phantasmagorical SF, but also abrupt, jolting violence, frenzied cross-cutting, and nail-gnawing suspense. This is the very stuff of pulp adventure, yet made more urgent by a reservoir of earned emotion. Lives are risked, a world uncovered, and secrets revealed (my favorite being the backstory of Ell, the ship's non-binary mechanical whiz). I could hardly hold on to my chair during the last hundred pages! Yet mostly On a Sunbeam is a story about love. The word that keeps coming back to me is tenderness, and Walden hits the tender spots again and again, not with cynical knowingness but with the thrilled self-discovery of an explorer who has just realized what her explorations are about. Relationships deepen, and at some point we realize—that is, Walden shows us—that On a Sunbeam is not simply the story of a single idealized love but of loving community, and of what it means to take others as they are. It's a story about unlike people forging bonds of mutual respect and care. Among the many exciting climaxes in the book, the most important ones, to me, are embraces. On a Sunbeam wears its heart on its sleeve. All this is delivered with the utmost grace, with a style whose delicacy reminds me of C.F. (Powr Mastrs) and whose out-of-this-world gorgeousness calls to mind Takemiya and Moto Hagio, those masters of shojo manga SF. Remarkably, Walden's style hardly ever betrays signs of underdrawing; the characters and panels seem to have found their perfect form without hesitation. Her style might be considered a variation on the Clear Line—clean contours, no hatching, and the use of contrasting solid blocks of color to solidify form—but without the cool meticulousness and literal, mimetic colors that such a comparison would imply. She's freer, and her light, unfussy lines are elegance itself. This is the more remarkable because her characters, emotionally, are all about undercurrents and anxiety; Walden renders their struggles with an unerring economy even as they're going through hell. Open white space, blocks of color and of darkness, the selective paring of background details—all these artistic strategies bring the story into crystalline focus. The spareness and cleanness of Walden's pages belie, or rather render all the more piercingly, the struggles going on among and within her characters: In my comics classes, I like to say that every book of comics teaches you how to read it, becoming its own instruction manual. That is, no generalized understanding of "comics" as a whole is going to make every new comic you encounter easy to understand, because comics aren't as formally stable and consistent as that. Instead, the form shifts, or artists shift it, toward new strategies and purposes—but attentive readers will learn how to read in a comic's particular way. I think about this when I see pages like the above, or On a Sunbeam's climactic pages: Coming at these pages unprepared, sans context, I would hardly know how to read them. But it's a testament to Walden's skill, and the gripping human story she tells, that these spare pages speak volumes to me now. On a Sunbeam is full of payoffs like this; it's masterful. It's also moving and exhilarating. As I said, uncanny. PS. I was sorry to miss Walden's conversation with Jen Wang at L.A.'s Chevalier's Books on Oct. 8. But I look forward to her signing and exhibition at Alhambra's Nucleus gallery on Feb. 22. First Second Books provided a review copy of this book. (Note: It was particularly challenging to scan pages from On a Sunbeam, a roughly 6 x 1.5 x 8.5 inch brick!)

|

Archives

June 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed