|

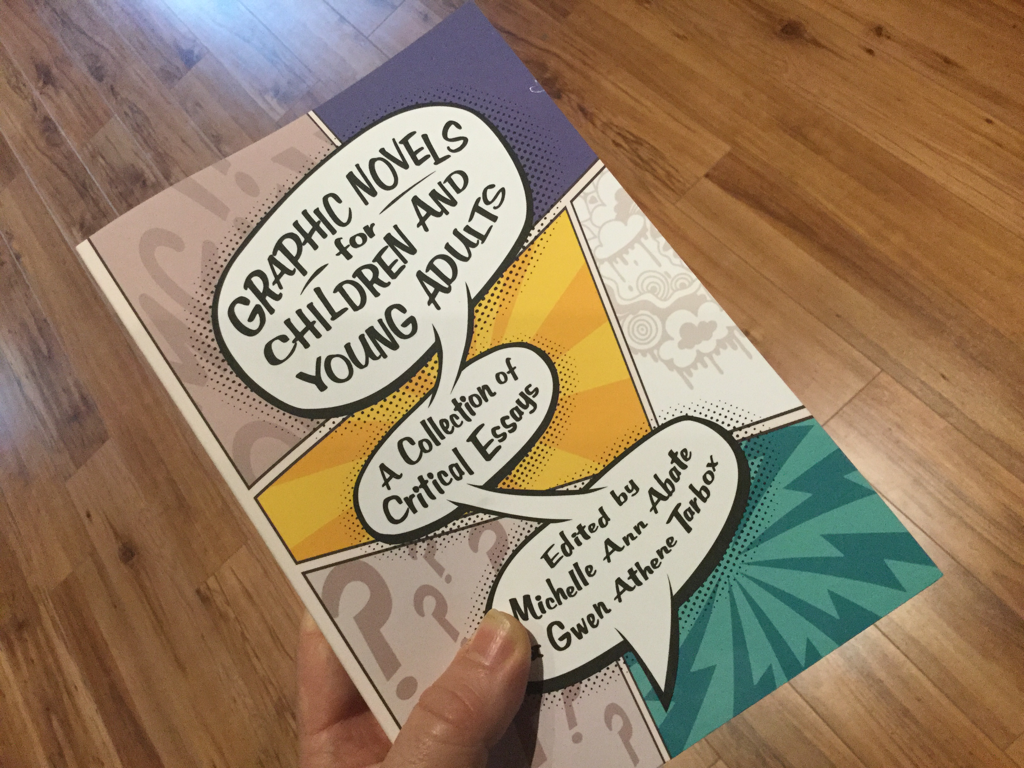

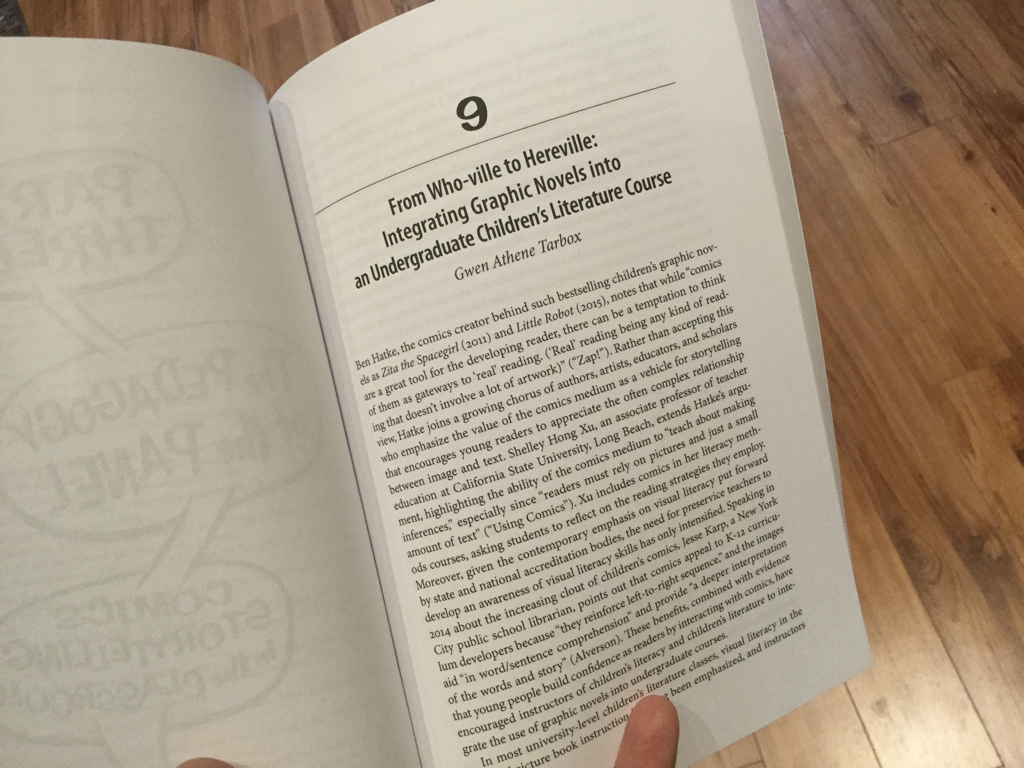

Graphic Novels for Children and Young Adults: A Collection of Critical Essays. Edited by Michelle Ann Abate and Gwen Athene Tarbox. University Press of Mississippi, 2017. ISBN 978-1496818447. Paperback, 372 pages, $30. Newsflash! Graphic Novels for Children and Young Adults (2017), edited by Michelle Ann Abate and Gwen Tarbox, and including a score of essays by diverse authors, has just been (re-) released in paperback. It came out last year, but now, at last, I have a softcover copy of my own that I can annotate and mark up in the usual ruthless way. Yes! This is an essential collection, a landmark in the academic consideration of children's and Young Adult comics. Readers of Gwen's contribution to our Teaching Roundtable may know, or may wish to know, that her post builds on and adds detail to ideas set forth in this book, specifically in her essay, "From Who-villle to Hereville: Integrating Graphic Novels into an Undergraduate Children's Literature Course." Also, Roundtable participant Joe Sutliff Sanders has an essay in the book on children's digital comics! I haven't quite figured out how to teach English 392 yet, but I do know that this is going to be one of the required texts.

0 Comments

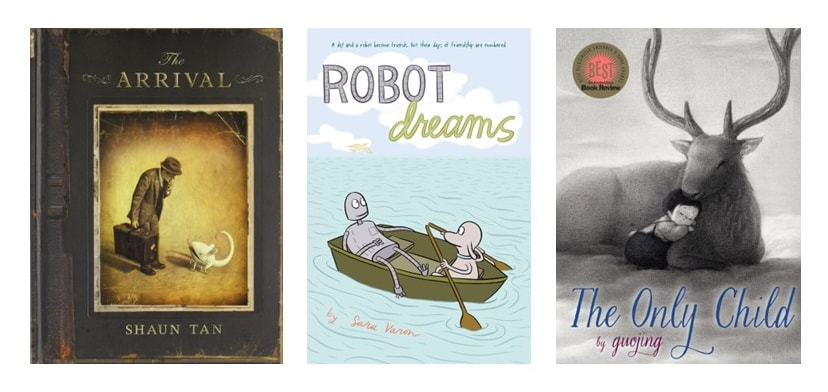

A guest post by Gwen Athene Tarbox The KinderComics Teaching Roundtable continues! Today my colleague Dr. Gwen Athene Tarbox, expert in comics and children's literature and co-editor of the essential Graphic Novels for Children and Young Adults (2017), responds to posts by me and Joe Sutliff Sanders regarding the challenges of teaching comics for and about children. This series arises from my preparations for teaching (this coming Fall) a seminar called Comics, Childhood, and Children’s Comics. Gwen, thank you for contributing your voice here! - Charles Hatfield When it comes to identifying strategies for teaching children’s comics, context matters. As Charles embarks upon the process of developing an elective honors seminar, ENGL 392, Comics, Childhood, and Children’s Comics, he knows that his students have at least some interest in comics and are probably used to researching and writing about interdisciplinary subject matter. The Department of English at California State University, Northridge frequently offers courses in popular culture, and Charles is one of a number of faculty members who integrate comics into their syllabi. Could there possibly be a downside to teaching childhood and children’s comics within a supportive academic environment? Well, not really, but as Charles tells us in his roundtable post, being faced with a seemingly unlimited set of topics and approaches at the nexus of two complex fields makes for a daunting task. Joe, a Lecturer in the Faculty of Education at the University of Cambridge, teaches in a system where students are exposed to a variety of instructors and subjects related to literature, education, and the history of education, as part of a three-year program that combines seminars with tutorials. As he explains in his roundtable post, “I have about two hours to give the students a fiery introduction to the material that will drive them to go educate themselves about the subject once I’m gone.” Many of Joe’s colleagues are interested in visual culture, as are the undergraduate and graduate students with whom he works, but the UK university system relies upon students being much more self-directed, so Joe may end up doing more of his teaching informally, in conferences with individual students. His concerns about teaching canonical texts, which are overwhelmingly male and White, should be shared by anyone who teaches in our fields, and Joe may have to rely upon handing out bibliographies and carving out an online or podcast resource for his students to ensure that they are familiar with a broad spectrum of comics texts. My own experience in the Department of English at Western Michigan University involves integrating comics into ENGL 3820, Literature for the Young Child, and ENGL 3830, Literature for the Intermediate Reader, courses that are required for elementary education majors, but can also serve as general education electives. Creative writing majors, inspired by the success of J.K. Rowling, Jacqueline Woodson, and Kwame Alexander, view 3820 and 3830 as venues for unlocking the secrets of character development or comparing how different media impact the way a narrative unfolds. However, regardless of their motivations for taking my courses, all but a few of my students tell me up front that they are AFRAID of comics—perhaps not as afraid as they are of taking Math 2650, Probability and Statistics for Elementary/Middle School Teachers… but for at least some of my students analyzing comics appears to be as terrifying as being asked to switch on their calculators. My context—preparing future teachers and aspiring authors—compels me to select texts that are frequently used in classrooms or are cutting-edge in terms of their form, and also means that many of my students are encountering comics for the very first time. Typically, I ease my children’s literature undergraduates into the study of comics by spending most of the semester focusing on visual rhetoric, first with picture books and illustrated novels and then moving on to hybrid texts such as Lorena Alvarez’ Nightlights and to films like Paddington or Coco. Then, on the first day of class devoted solely to comics, I hand out a few wordless offerings--Shaun Tan’s The Arrival, Sara Varon’s Robot Dreams, or Guojing’s The Only Child—and ask students to read them aloud. Reading aloud has become a major component of our children’s literature courses, so when students appear flustered and hesitate, it is not because they are unaccustomed to reading in front of their peers. Rather, they are hesitant because, and I give voice here to my students: “How do I know what to read first? What if I interpret something incorrectly? Do I take in the whole page first and summarize it? Or do I talk about each panel? Who is the narrator? Where is the narrator?” All of these questions lead us to a nuts-and-bolts discussion of form and content that occurs organically and is supplemented by excerpts from a variety of critical texts, including Joe’s essay, “Chaperoning Words: Meaning-Making in Comics and Picture Books” (Children’s Literature, 2013), Charles’s “Comic Art, Children's Literature, and the New Comic Studies” (The Lion and the Unicorn, 2006), and Paul Karasik and Mark Newgarden’s newly released How to Read Nancy. Since 2017, I have been working on a book, Children’s and Young Adult Comics, that will come out later this year from Bloomsbury Academic. Like Charles, I have struggled to carve out a narrow enough focus, and like Joe, I feel as if I have only a few short chapters to encourage readers’ investment in children’s comics. Writing an introductory guide to children’s comics has a lot in common with teaching children’s comics insofar as I spend as much time worrying about what I have left out as I do about what is actually on the page. Another venue that has contributed significantly to my understanding of how to share comics with my students is the Comics Alternative Young Readers podcast that I have been a part of since 2015. Working first with Andy Wolverton, and now with Paul Lai, I have had the chance to read dozens of children’s and YA comics every year and to talk about them with experts. Derek Royal, who co-founded and now runs The Comics Alternative, is another great resource whom I consult regularly and with whom I have interviewed a number of children’s comics creators, including Mairghread Scott, Tony Cliff, and Hope Larson. Finally, I was fortunate enough to co-edit Graphic Novels for Children and Young Adults: A Critical Collection (University of Mississippi Press, 2017—now available in paperback), with Michelle Ann Abate, and the process introduced me to over twenty scholars, from traditional literary critics to teacher educators to visual theorists and cultural studies experts, all of whom provide in-depth analyses of a host of contemporary children’s and YA comics. What heartens me the most, then, is that a large community is beginning to congregate around the study and teaching of children’s and YA comics. Charles and Joe, Laura Jiménez, David Low, Nathalie op de Beeck, Carol Tilley, Michelle Ann Abate, Philip Nel, and countless other amazing scholars are helping to create an ongoing dialogue about the intersection of two fields whose fortunes have often been linked, but have rarely been discussed together. And now we have KinderComics, Charles’s blog, as another important resource! (Note: this roundtable will continue in the weeks and months ahead. - CH) Gwen Athene Tarbox is a professor in the Department of English at Western Michigan University, where she teaches courses in children's and YA literature, as well as comics studies. She is the author of The Clubwomen's Daughters: Collectivist Impulses in Progressive-era Girls' Fiction (Routledge, 2001), co-editor with Michelle Ann Abate of Graphic Novels for Children and Young Adults: A Critical Collection (UP of Miss, 2017), and author of an upcoming monograph, Children's and Young Adult Comics, from Bloomsbury Academic. She has written articles on the comics of Hergé and Gene Luen Yang, on teaching comics, and on various topics related to children's literature. She is also co-host, with Paul Lai, of The Comics Alternative's Young Reader podcast, which airs towards the end of every month (www.comicsalternative.com).

A guest post by Joe Sutliff SandersMy colleague Dr. Joe Sutliff Sanders has kindly agreed to follow up my initial post in a series that I'm calling our Teaching Roundtable. This series stems from my preparations for teaching, in Fall 2018, a course called Comics, Childhood, and Children’s Comics, and my thoughts about the challenges of designing such a course. Thanks, Joe! - Charles Hatfield The best teaching that I have ever done has always been set up just beyond the edge of what I actually understand. You’ll hardly be surprised to learn, then, that I am in love with the idea of this blog. Charles does know a thing or two about comics, but he’s starting this blog conversation about the course not with what he knows, but with where he knows he’s going to have problems. It’s sick; it’s beautiful. I love it. As fate would have it, I happen to be in a very good situation to think about what can go wrong teaching childhood and comics. I’ve just relocated to Cambridge, where the teaching is very, very different from what I’ve done (and experienced) in every other classroom. The number one problem that I keep experiencing is that when the nature of the course wants us to lecture about the center, the books that Have To Be Known, then that nature is insistently nudging us away from the rich work done by people on the margins. For me, this urge toward the center is constant because at Cambridge we teach in a model that might best be understood as serial guest lecturing. Students have a different instructor almost every week, and once I have taught my subject, it might well never come up again for the rest of the term—indeed, the rest of the year. I have about two hours to give the students a fiery introduction to the material that will drive them to go educate themselves about the subject once I’m gone. If I can only ask them to read one book to prepare for my day in front of them, don’t I have to assign them the most canonical, traditional, familiar, central…let’s call it what it is: White…text possible? And Charles isn’t going to find the challenge much easier. Yes, he has the same students for a few months, so with some judicious selection, he can assign both the center and the margin. But there will be times when the nature of the subject seems to insist on safe, familiar choices. For example, while talking about the Comics Code, which was developed by influential White businessmen to protect their interests by playing to 1950s sensibilities of American middle-class propriety, how will he escape a reading list that is White, White, White? The men whose comics sparked the outrage were White; the public intellectual at the center of the debate was White; the men who wrote the Code were White; the books that thrived under the new regime were White. What reading material central to this history will be about anything but Whiteness? Or how about teaching the origins of cartooning? The most common version of the history of comics is populated by White Europeans who had access to the training and venues of publication necessary for a career as a public artist. I’m uncomfortable (to put it mildly) with a module featuring only them, but what are you going to do, not teach the center? These problems arise from comics as a subject matter, but there’s another problem rooted even more deeply in the specific aspect of contexts that Charles has chosen. The title of the course pinpoints "childhood," yes? Childhood’s close association with innocence, which is itself associated with Whiteness (if you don’t believe me, ask Robin Bernstein), is going to make straying from the center even more problematic. Here, as above, the enemy he faces is the nature of the subject. But there is another potential enemy. If—or, knowing Charles, when is the more appropriate word—he edges the reading list and classroom conversation away from innocence, will his students still recognize what they are reading as children’s comics? It’s not just the institution and the subject matter that insist on staying safely in the zone of the canonical…it’s frequently the students as well. So will his students resist when the reading list includes perspectives that don’t fit with the general notion of lily-White childhood? Charles asked me here only to point out his looming problems, but I feel some tiny obligation to offer some possible solutions, too. For example, when teaching the origins of comics, it might do to teach a competing theory, namely the theory that what we call comics today owes a debt to thirteenth-century Japanese art. Frankly, I don’t find that theory convincing (though I think that the influence of another Japanese art form, kamishibai, on contemporary comics has potential), but so what? Our job isn’t to teach proved, finished intellectual ideas, but to help train students to struggle with ideas on their own, and giving them a theory that mostly works will put them in the position of critiquing (or improving) it themselves. Another idea: rather than letting innocence and Whiteness be default categories, rather than letting them force us to defend any deviation from their norms, make them subjects. This is the brilliant move that feminists made with the invention of "masculinity studies": take the thing that has rendered itself invisible and make it the object of study. I’m still concerned that we’ll wind up with all-White reading lists, but this strategy allows us to observe the center without taking the center for granted. Wow, that was fun! Who knew that pointing out other people’s problems and then walking away whistling would be so liberating? Thanks for the invitation, Charles, and I can’t wait to read the posts from the upcoming comics scholars. (Up next: Dr. Gwen Athene Tarbox!) Joe Sutliff Sanders is Lecturer in the Faculty of Education at the University of Cambridge. He is the editor of The Comics of Hergé: When the Lines Are Not So Clear (2016) and the co-editor, with Michelle Ann Abate, of Good Grief! Children and Comics (2016). With Charles, he gave the keynote address on comics and picture books at the annual Children’s Literature Association conference in 2016. His most recent book is A Literature of Questions: Nonfiction for the Critical Child (2018). This post is about teaching. As I said when I started KinderComics, one of my goals in doing this blog is to brainstorm publicly about a course I'll be teaching this coming Fall 2018 semester at CSU Northridge: an English Honors seminar titled Comics, Childhood, and Children's Comics (English 392). Despite having taught at the intersection of comics and children's culture for years (including bringing comics into my entry-level Children's Literature class and designing courses on picture books that also explore comics), this upcoming Honors seminar marks the first time I've actually pitched a course devoted to children's comics per se. I'm excited about the prospect, and honestly a bit daunted by it too. Why daunted? Comics and childhood, together, make for a sprawling, complex area—and perhaps you can tell from my course's title that I haven't yet committed to a particular focus. Which is to say that I haven't decided how to delimit the course or what objectives to put front and center. I've been thinking about those things for a while. Thing is, the students and I will have fifteen weeks together, which in practice, experience tells me, means about twelve weeks tops for introducing new readings. What's more, part of the brief for an Honors seminar with, say, between a dozen and twenty students is that the students take turns presenting to and teaching one another, sharing the results of deep, self-directed research (fitting challenges for an advanced course). So it seems clear that I'll have to make some severe choices when it comes to focusing down. Yow! I've thought of at least four potential foci that are important to me:

All these areas seem important. Child characters are central to the satirical and sentimental uses of comics and to the form's popular spread; the history of moral panic is crucial to understanding comics' reputation, even now; the depiction of childhood in adult texts is key to the burgeoning alternative comics and graphic memoir canon, from Binky Brown to My Favorite Thing Is Monsters; and the sheer popularity of graphic novels for young readers today is a trend so dramatic as to throw all the other areas into a new light. So, the question for me is, what objectives do I want students to achieve as they work at the crossroads of comics and childhood? With all this in mind, I'm inviting several of my close colleagues in children's comics studies to join me here in an intermittent series of posts that I'll call a Teaching Roundtable. This roundtable will amount to, again, brainstorming, and perhaps debating the importance of our different teaching objectives. First up, TOMORROW, will be Dr. Joe Sutliff Sanders, author of, among other things, the new book A Literature of Questions: Nonfiction for the Critical Child (U of Minnesota Press, 2018), editor of The Comics of Hergé: When the Lines are Not So Clear (UP of Mississippi, 2016), and faculty member at the Children's Literature Research Centre at the University of Cambridge. Joe will be following up on this initial post -- readers, please come back tomorrow to follow and chime in on the discussion! Add your voices! Thanks.

|

Archives

June 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed