|

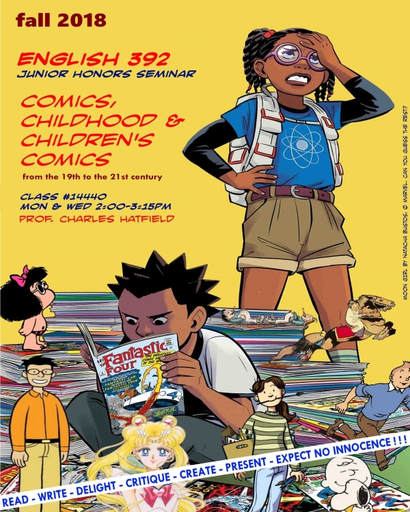

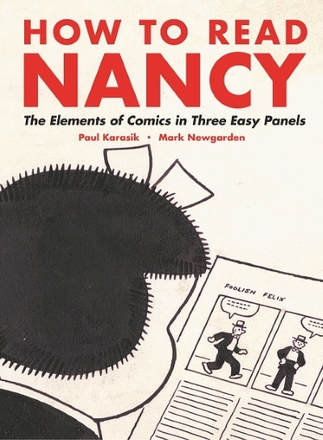

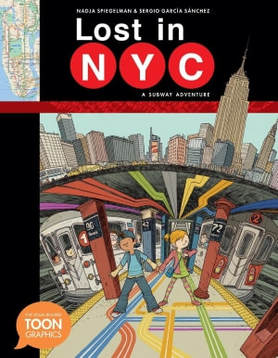

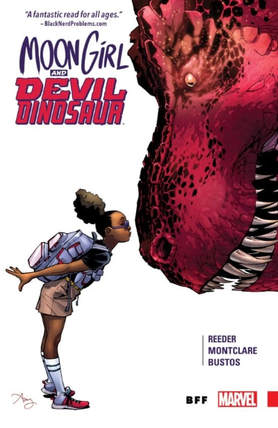

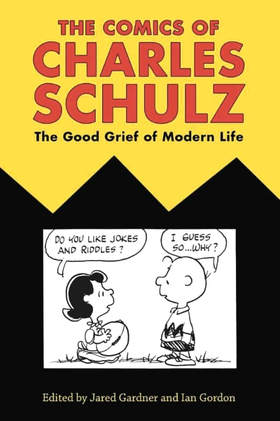

I continue to wrestle with the design of my my upcoming Fall 2018 course, English 392: Comics, Childhood, and Children’s Comics. My impulse is to focus mainly on the current (i.e. post-2005) boom in children’s and young adult graphic novels in the US, which is what sparked or inspired the class in the first place. Therefore it seems to me that books by Jeff Smith, Raina Telgemeier, and Gene Luen Yang have to be in the mix; exposure to those very successful and influential authors will help lay the groundwork for what's happening today. At the same time, we do need to address the vexed larger history of children’s comics; it seems vital to at least sketch in the histories of newspaper strips and comic books vis-à-vis children (and what of seminal children's comics from, say, Japan, Europe, or Latin America?). So, juggling all this continues to be an intellectual and practical challenge. That said, at this point it seems likely to me that the following books, or selections from them, will be represented in our required reading list: I'm still working out many issues, including the need for greater diversity in genre, format, and cultural content, the scheduling of student presentations and guest speakers, and of course costs. So I would not call this anywhere near the final list. But it's a hint as to where my head is currently at. Frankly, the list is too US-centric for my tastes, but I may have to live with that, given time constraints. I'm not quite sure yet. Work-wise, I'm envisioning student discussion launchers most weeks, a seminar paper (preceded by a formal prospectus), and a weekly or semi-weekly online discussion forum, which is something I can only do when a class is fairly small. I'm also hoping for three to four guest speakers, one a scholar, one a children's publishing pro, and one a comics creator. I hope that one or more of my scholarly colleagues at CSUN can pay a visit as well.  Whew! We'll see. Readers, click on the category "392" if you'd like more behind-the-scenes info on this evolving course...

3 Comments

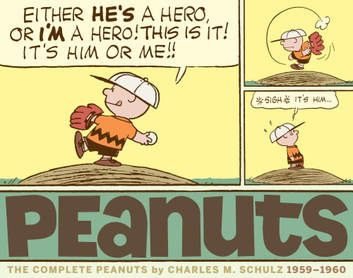

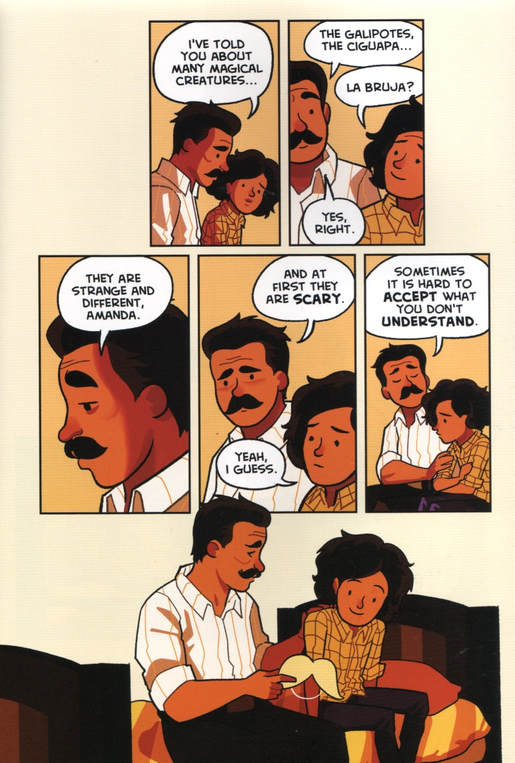

The Cardboard Kingdom. By Chad Sell, with Vid Alliger, Manuel Betancourt, Michael Cole, David Demeo, Jay Fuller, Cloud Jacobs, Kris Moore, Molly Muldoon, Barbara Perez Marquez, and Katie Schenkel. Alfred A. Knopf/Random House Children’s Books, June 2018. ISBN 978-1524719371. Hardcover, 288 pages, $20.99. The Cardboard Kingdom celebrates community and in fact is the work of a community: a team made up of cartoonist and creator Chad Sell and ten co-writers, referred to by the publisher as “new and diverse authors” (one of whom, Kris Moore, sadly seems to have passed away). An impressive collaborative feat, it depicts an idealized neighborhood of kids who also collaborate, turning their everyday lives into, basically, a nonstop live-action roleplaying game. A paean to shared creative play—essentially, the book is about kids as cosplayers, crafters, and friends—it must also have been a playful, if complicated, project. Happily, everything clicks. The book works as an anthology of short stories and vignettes, from about five to thirty-plus pages in length, but more powerfully as a novel, which, though episodic, designedly builds to a big and satisfying finish. Sell enlisted each author to write a story or two, and then apparently brought them together to cook up the boffo finale. Reading it straight through, it’s almost seamless; the novel builds its neighborhood carefully, gradually introducing new characters into its busy communal scenes. Though the publisher says The Cardboard Kingdom is about “sixteen kids,” I counted nineteen distinct, recurring child characters in the novel, some identified only by their roleplaying names, some known by more than one name. There’s a lot of juggling going on, but never to the point of distraction. The publisher also says that the book depicts “adolescent identity-searching and emotional growth”—yet it certainly isn’t YA fiction. My sense is that The Cardboard Kingdom is emphatically a middle-grade novel, aiming for upper elementary to perhaps middle school age. While its large cast, complex rigging, and lively and dynamic pages say “middle-grade” to me (not younger), its eager, almost ingratiating cartoon style reminds me of Pixar—say, Inside Out, with its mix of emotional gravity and toylike cuteness. Certainly the book depicts identity-searching and emotional growth; however, its bright cartooning, winsome children, and almost Peanuts-like sense of suburbia (not wholly idyllic like Schulz’s but still reassuringly safe) seem pre-adolescent in tone. Its let’s-pretend and DIY ethos brings back some early memories of my own. I mention this not because I’m concerned about age levels (KinderComics doesn’t usually focus on leveling) but because I’m interested in The Cardboard Kingdom’s treatment of identity, which I consider bold for a middle-grade novel. If graphically the book suggests years of reading Peanuts and Tintin, its imagined neighborhood has a utopian queer- and trans-positive vibe that would make it a good companion to, say, Alex Gino’s groundbreaking George (also a middle-grade fiction). Among the book’s young role-players are several who defy or ignore gender norms. In fact the first story, “The Sorceress,” written with Jay Fuller, introduces a cross-dressing pair: the titular Sorceress, soon shown to be (ostensibly) a boy but only much later identified as “Jack,” and his neighbor, a seeming girl who refuses the princess role and becomes The Knight (I don’t think she ever gets another name). Reportedly, this story was the kernel or inspiration for the whole book. There’s more: one character, Sophie, defies expectations of sweet girlishness and becomes a rampaging, Hulk-like bruiser she calls The Big Banshee; another, Amanda, a self-styled Mad Scientist, worries her father by wearing a mustache. Meanwhile, the relationship between Miguel the Rogue and Nate the Prince hints at a young gay crush. The Cardboard Kingdom, in fact, resists conventional gender and sexual roles throughout. For all that, it’s a story about kids who like to imagine combat: big, frenzied dust-ups between heroes and villains. Reading it, I was more than once reminded of an Avengers movie. If the drawing style and solid, bright colors follow a clear-line aesthetic, recalling the moral and ideological sureties of so many children’s comics, then Jack Kirby is surely a reference point too, from the Big Banshee’s unabashed monstrousness (more cheerful than tragic here) to the outrageous costuming, replete with spiky cardboard headgear that would do Cate Blanchett proud. The book taps the same vein of explosive fantasy that superhero comics do, but with more charm than most. The neighborhood kids of The Cardboard Kingdom, though they never really hurt one another, like to run around and fight; Sell and company are unafraid of children’s capacity to play at physical conflict and violence. Further, many of the kids like to be “bad guys” as well as “good,” and the book gleefully mines that tendency for humor. There’s a disarming mixture of sweetness and brutal imaginings in the book, though it all comes out seeming like harmless fun. Sell and his collaborators have a feel for the reckless, revved-up fantasy lives of young kids hanging out together--I appreciate that. And no adult ever dictates the terms of, or reins in, what the kids are fantasizing about. The book presents an entirely child-driven and child-centered world of cooperative, if pugnacious, play. In short, it’s feisty as well as sweet. Behind its bright, cheery surface, then, The Cardboard Kingdom is structurally tricky and thematically gutsy. On the critical side, I would say that some of its component stories resolve too quickly; the book runs the risk of being too neat, because its nested structure and sheer number of characters demand fast pacing, even when dealing with hard matters of identity and parent-child tension. Problems are invoked and solved with speed. In that sense, it’s, again, utopian. Also, the book makes some obvious, even heavy-handed, didactic moves, though in the direction of adult chaperones rather than child readers. Its sharpest lessons will likely be ones of forbearance and acceptance aimed at concerned parents whose children are behaving, well, unexpectedly. The best examples of parenting in The Cardboard Kingdom involve suspending or tempering judgment, i.e. being brave about children’s imaginative self-fashioning (would that all anxious parents course-corrected as readily as those in the book). But, most of all, it’s the book’s wise embrace of childhood play that makes The Cardboard Kingdom a brave and interesting graphic novel, one I highly recommend. Random House provided a review copy of this book.

Forgive me for interrupting KinderComics' coverage of children's and young adult comics to report on something else (albeit something related) that is near and dear to my heart: The 2018 officer elections for the Comics Studies Society ended last week, and I want to congratulate new CSS Board officers Colin Beineke, Leah Misemer, and Matt Smith, the newly reelected Nhora Serrano, the newly appointed Samantha Langsdale, and a new slate of Graduate Student Caucus officers including Bryan Bove, Biz Nijdam, Adrienne Resha, and Hanah Stiverson! Here is the full roster of the CSS Board at present:

Thanks to outgoing Member at Large Christy Blanch and outgoing Social Strategist and original Web Editor A. David Lewis! Thanks also to new VP Matt Smith for his two years of service as a Member at Large. (And thanks to emeritus founding officers Corey Creekmur, Brian Cremins, Rebecca Wanzo, and Qiana Whitted, who were part of the very first Board elected in late 2014.) You may notice that I'm the "Immediate Past President," which means that, yes, after several years on the job, I have stepped down from the Presidency and been succeeded by the very capable, tireless, and inspiring Carol Tilley! Carol is now spearheading plans for our first CSS conference, Mind the Gaps, to be held this August 9-11 at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign. This innovative, forward-looking conference will include nearly fifty sessions, more than 140 program participants, and an array of special events—check it out! Per the CSS bylaws, I'll be serving on the Board for one more year, though no longer in a leading role. It has been my pleasure, and a source of great pride, to preside over the founding and early development of the CSS, and to work with such talented colleagues to envision and help ensure the future of Comics Studies. And it is my very great pleasure to pass the torch to Carol and all those who will come after. FYI, the CSS is a professional association and learned society for comics scholars, dedicated to (as our official mission statement says) "promoting the critical study of comics, improving comics teaching, and engaging in open and ongoing conversations about the comics world." The Society "celebrates and seeks to foster diversity in comics studies, including diversity in scholarly discipline, career position, job niche, and cultural and personal identity." Readers, if you're passionate about comics studies but don't know the CSS, I urge you to check us out—and feel free to contact me via this blog if you have questions! PS. As of yesterday, May 21, the CSS has just announced the winners of its inaugural prizes for scholarly writing:

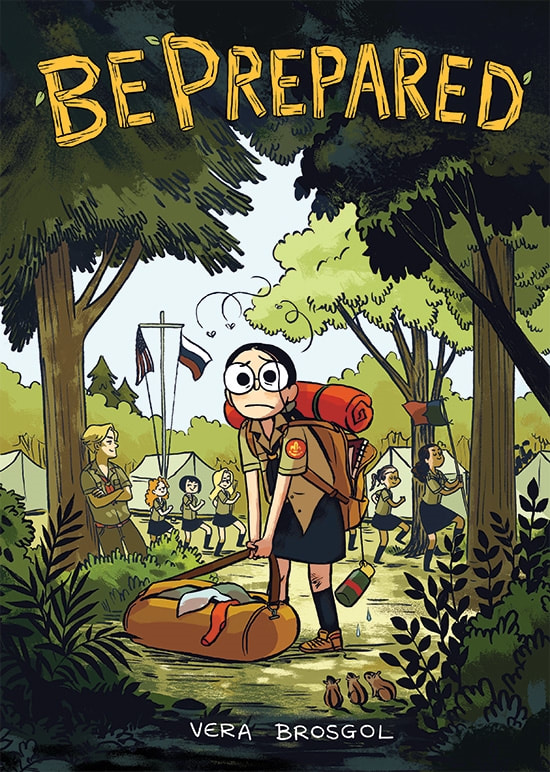

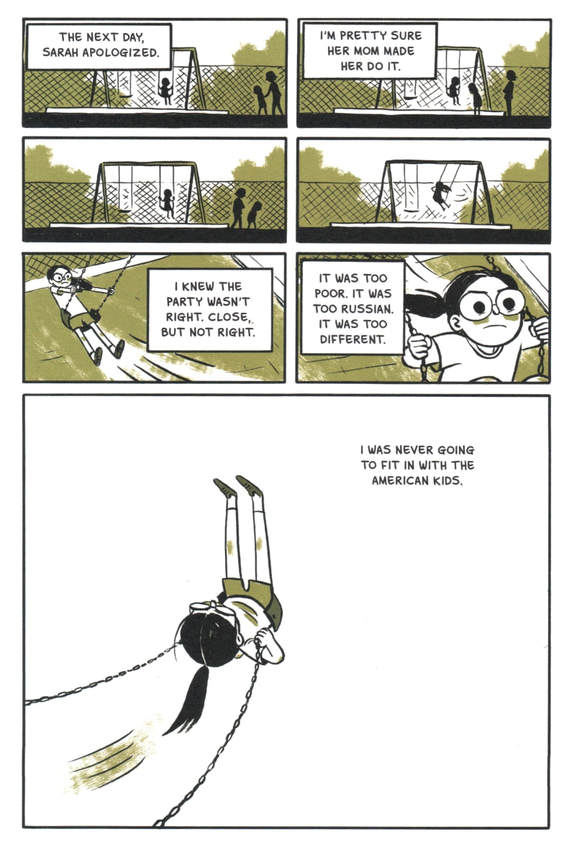

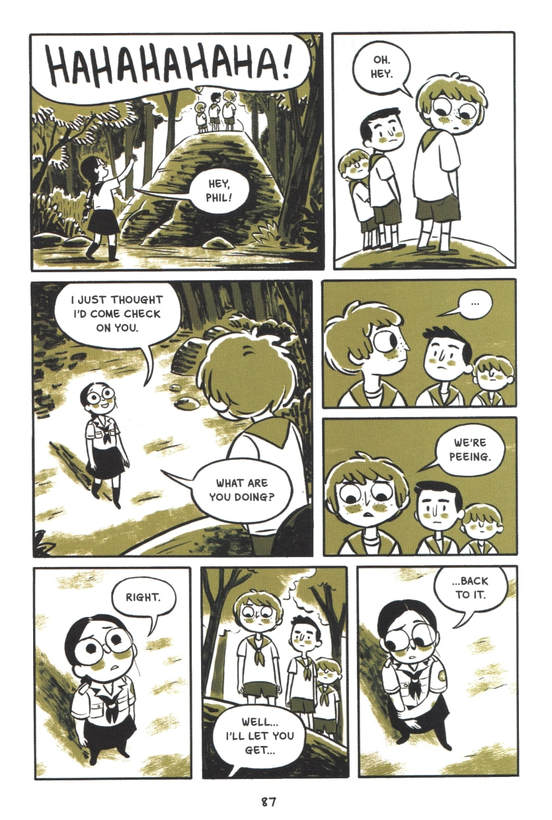

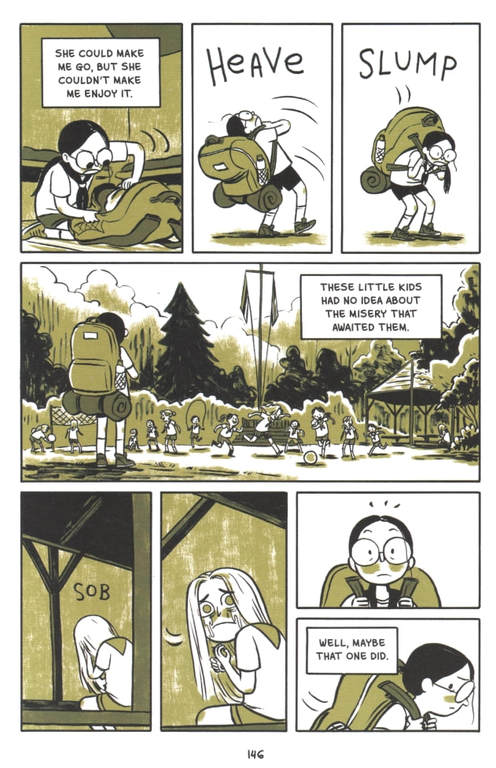

The first-ever CSS Book Prize goes to Brannon Costello of Louisiana State University for Neon Visions: The Comics of Howard Chaykin (Louisiana State UP). The first-ever CSS Article Prize goes to Benoît Crucifix of the University of Liège and UC Louvain for "Cut-Up and Redrawn: Charles Burns's Swipe Files" (Inks 1.3, Fall 2017). The Chute Award for Best Graduate Student Conference Presentation goes to Alex Smith of the University of Cincinnati for "Breaking Panels: Gay Cartoonists’ Radical Revolt." (Chute Award judges also recognized three honorable mentions: Michael Grifka of the Ohio State University, Maite Urcaregui of UC Santa Barbara, and Andrea Horbinski of UC Berkeley.) With these awards, the CSS inaugurates a new tradition of prizes awarded by comics scholars to comics scholars. I hope you can join us at our conference in August to witness the official conferral of these prizes! Be Prepared. By Vera Brosgol. Color by Alec Longstreth. First Second Books, April 2018. 256 pages. Hardcover, ISBN 978-1626724440, $22.99. Softcover, ISBN 978-1626724457, $12.99. Book design by Danielle Ceccolini and Rob Steen. About seven years ago, animator and storyboard artist Vera Brosgol entered the world of graphic novels with a walloping big success: Anya's Ghost, a supernatural fantasy rooted in the experience of being a Russian immigrant girl struggling to fit into American life. Brosgol knew this struggle firsthand, having moved from Russia to the US at age five. Anya's Ghost changed Brosgol's life: rapturously reviewed, the book went on to win Eisner, Harvey, and Cybil Awards. Its theme of trying to disavow one's cultural roots resonated with Gene Luen Yang's epochal American Born Chinese, which had been published some five years earlier (both were published by First Second). The two books drew upon popular genres—myth fantasy, superheroes, ghost stories—to fashion nervy fables of complex and ambivalent identity. In that sense, Anya's Ghost appears to have struck a nerve. Now Brosgol, having also authored a Caldecott Honored picture book (2016's Leave Me Alone!), has just released her second graphic novel: the autobiographical Be Prepared, in which a nine-year-old Vera, again a self-conscious Russian immigré, goes to summer camp. Be Prepared is in the same vein of comic memoir as Raina Telgemeier's hugely popular Smile (2010) and Sisters (2014), and indeed the book is being promoted in that light (and has been blurbed by Telgemeier herself). Thematically, however, it pairs with Anya's Ghost, as it mines Brosgol's experience as an immigrant to tell another story of the struggle for identity. This time, though, the story happens in the company of many other Russian kids, in the context of a Russian immersion camp with Orthodox roots. From this intriguingly specific setting, Be Prepared builds a book that turns out to be, tonally, quite different from Anya's Ghost, yet is just as wonderful. Be Prepared begins with, once again, the discomfort, or even humiliation, of being a markedly Russian girl in a suburban American world dominated by unmarked middle-class Whiteness. Yet, whereas Anya's Ghost centers on a somewhat sullen and alienated adolescent, and thus tacks in the direction of Young Adult fiction, Be Prepared's Vera is naive, hopeful, and intimidated by teens. Yet she is worldly-wise enough to know that she sticks out like a sore thumb, that she is too ethnic, "too different," to fit easily into her town and school in Upstate New York. Indeed Vera is painfully aware of being "too poor" and "too Russian" to blend in with her schoolmates. However, whereas Brosgol's Anya seemed determined to shed her Russianness, Vera thrills to the prospect of attending an all-Russian camp in the New England woods. Most of her schoolmates go away to camp every summer, leaving Vera adrift and bored, but when she learns of a camp where "everyone would be Russian like me," she dares to hope that it will ease the pain of being different. "I had to go," she says. "I had to go." Vera and her little brother Phil do go, and here is where Be Prepared takes off, as it conjures the distinctive setting of a Russian scouting camp, dotted with Russian signage and Orthodox icons. The setting appears to be (guesswork here) based on a real-life camp run by the Organization of Russian Young Pathfinders (Организация Российских Юных Разведчиков, or ORYuR) or some similar Russian Scouting in Exile group. It's all about being Russian, all the time. Camp songs are sung in Russian; Russian speech (a constant) is represented by English within brackets; and each week the boys and girls compete in a capture-the-flag contest called napadenya (attack). The problem is, camp sucks. Vera's hopes of fitting in are dashed: she is placed with older girls who patronize her, her Russian is too tentative, and roughing it freaks her out. Too late: she is committed, and has to stay. Thence comes much of the book's poignancy and humor. I appreciate the frankness, and sometimes rawness, of Brosgol's humor. As she did in Anya's Ghost, here again she tests what a young reader's book can get away with. The young campers of Be Prepared are emphatically people with bodies, and much of the book's comedy stems from putting those bodies under duress, as happens when you go camping. Bites, stings, toileting, and adolescent growing pains are all played for laughs, and many of the gags involve visits to the dreaded latrine. There's some pain behind the laughs. Brosgol's humor has a salty matter-of-factness that will likely ring true for just about anyone who's ever been to summer camp, as in this sequence where Vera pays her brother a rare visit: Or this mortifying moment between Vera and her two tent-mates: There is more to Be Prepared than these moments of rough humor and embarrassment. There's testing, growth, and self-recognition. There's struggle and loneliness, but ultimately affirmation (though thankfully no platitudes). And, man oh man, is there great cartooning. Be Prepared is a delight because Brosgol is an ace artist with a gift for designing characters, pacing stories, and building pages. The characters, as one might expect of a skilled animator, are clearly tagged, i.e. graphically distinct. Young Vera herself, moonfaced, with coke-bottle glasses and big, dark dots for eyes, is unmistakable: a live antenna of a character, veering from joy to misery, anticipation to disappointment. Brosgol cartoons her (that is to say herself) with comic brio, ruthless insight, and, yes, empathy. Other characters are vivid types, from Vera's teenage tent-mates, both named Sasha, to the cocky alpha male they compete over, to Vera's camp counselor, at first harried and remote, later sympathetic. Brosgol steers these characters and more through shifting moods, reversals, sometimes betrayals, and oh so many moments of cringing social awkwardness. Further, Brosgol's way with a page, her rhythmic sense of how to make each page build to a payoff, gag, shock, or suspenseful breath, is exhilarating. Her dynamically gridded pages, avoiding tedium but seldom grandstanding, serve the elastic rhythms of the storytelling, and wow does the story move. Though her methods are entirely traditional and convention-bound, Brosgol's sheer fluency is something to behold. Be Prepared is visually masterful, from exacting body language, to precisely observed physical business (camping, hiking, sneaking around), to the rare moments of, whew, calm. Much credit must go to the gorgeously worked surfaces of the pages, completed by the sumptuous coloring of Alec Longstreth, who works wonders with a riotous mix of greens (my scans, here, are too dull to do his work justice). For a strictly "two-color" book, green and black, Be Prepared is replete and ravishing, an opulent outlay of textures. Be Prepared is beautiful, gutsy, and funny. Granted, it does not have the Gothic horror of Anya's Ghost, and does not resonate quite so unnervingly. Rather, it's a breeze of a book, a charming, vivid comedy. Yet a closer look reveals moments of trouble and complexity that, as usual for Brosgol, are not tidily resolved but instead allowed to hang, unfinished and provoking. There are still doses of painful honesty behind the bright, emphatic delivery—and the ending somewhat short-circuits the expected lessons of growth and acceptance, to my delight. If Be Prepared isn't nominated for several awards next year, I'll eat my hat. Need I say that it comes highly recommended?

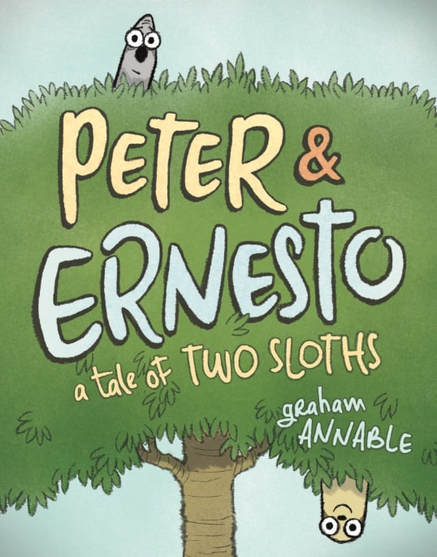

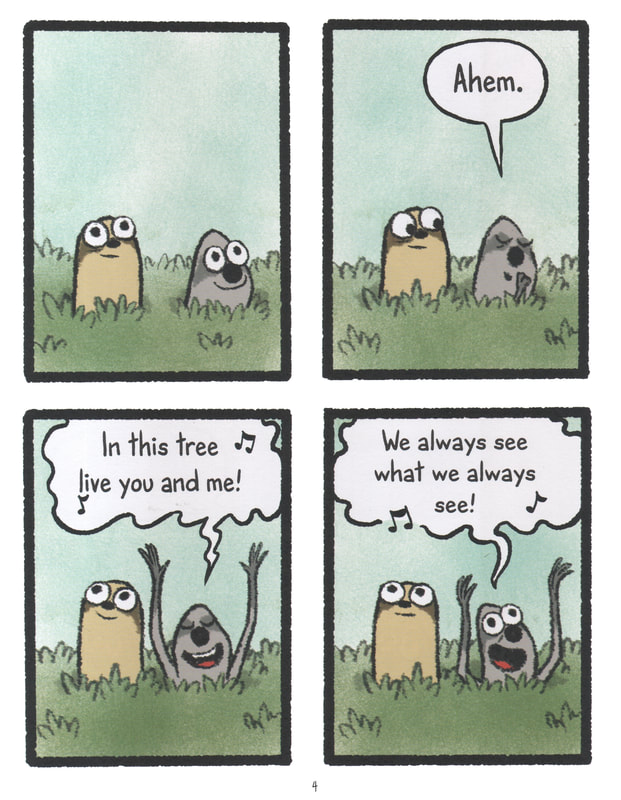

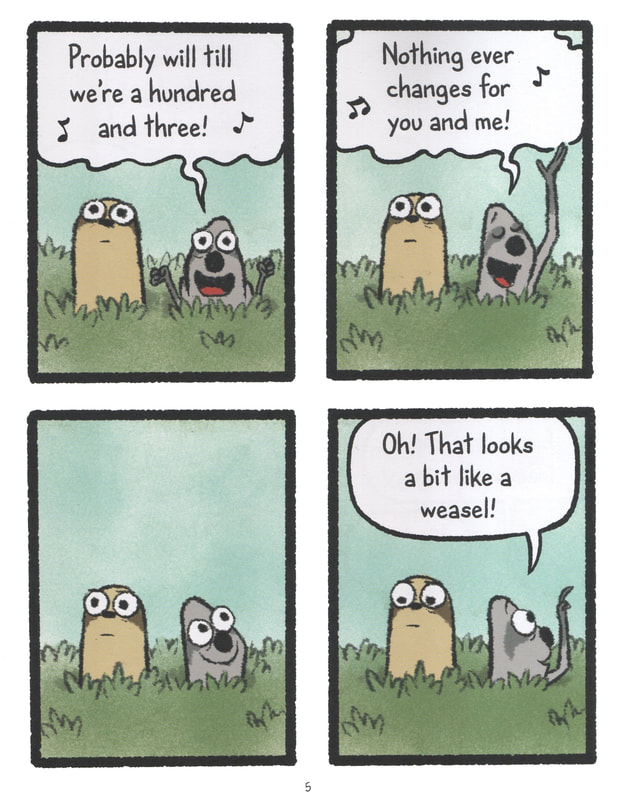

Peter & Ernesto: A Tale of Two Sloths. By Graham Annable. First Second, 2018. ISBN 978-1626725614. $17.99, 128 pages. Book design by Danielle Ceccolini. Cartoonist, animator, and director Graham Annable (The Book of Grickle, Puzzle Agent, The Grickle Channel on YouTube, etc.) is a wickedly smart humorist working his own distinctive vein of anxious, twitchy, sometimes disturbing comics, films, and games. At times his work is very dark: some readers may remember his tale "Burden" (Papercutter #3, Fall 2006), reprinted in The Best American Comics 2008 (edited by Lynda Barry). Sometimes his work is more eager to please, but still uneasy; I'd place the Laika film The Boxtrolls, which he co-directed, in that category. The various Grickle projects are pure Annable, a window onto his sensibility: nervous humor, odd beats, and bug-eyed characters who look a lot like Annable's own thumbnail image from Twitter: Peter & Ernesto is Annable's first children's book. It's terrific and strange: a buddy story in which the two buddies are mostly separated. One, Ernesto, seeks adventure and new experience. The other, Peter, craves security and sameness. They happen to be sloths. Their story begins in a treetop, as together the two of them indulge in the happy pastime of reading the shapes of clouds: a friendly idyll. Right away, though, the two diverge. As Peter joyfully basks in the unchanging familiarity of their lives, Ernesto begins to look—well, restless. And almost worried. As if the smallness of their shared world is closing in on him. The scene is tender, anxious, and funny, like the book as a whole: From there, Ernesto takes off to see the world, going where Peter dare not follow. But Peter’s concern for Ernesto overtakes his fear, and he sets out after his friend as if to protect him from the wide world—even though Peter can hardly bear to face that world himself. For much of the book, then, Peter follows belatedly behind Ernesto, so that the reader re-experiences places they have already visited, pages earlier—but it’s much different the second time around. As Ernesto revels in the unexpected thrills of his frankly improvised journey, Peter encounters the same scenes, and hurdles, with fear and trembling. There’s a lot of loopy business en route, much of it involving other comic animals, before a neat, affirming close. Annable’s comic timing his great, he mines Peter’s anxious qualms for tender, empathetic humor, and the world comes out seeming like a grand place. Implicitly, Peter & Ernesto is an odd-couple narrative for both brave, venturesome kids and diffident, anxious ones. There are a lot of children’s stories like this: depictions of sometimes contrasting and yet loyal friends. I hear an echo of Arnold Lobel’s Frog and Toad books here (Frog and Toad Are Friends and its four sequels, 1970-1979), and Annable has said that they were indeed an influence. Sesame Street's Ernie and Bert come to mind too. What I particularly like about Peter & Ernesto is its deft cartooning and comic timing—and the way Annable, a poet of nervousness, gets me to sympathize with both the world-conquering Ernesto and especially the timorous, uncertain Peter. Drawn in Photoshop with customized brushes, Peter & Ernesto boasts a ragged, trembling line and organic look. It is beautifully and subtly colored: Peter and Ernesto live in a great green and blue world. Yet it’s Annable’s shivery lines and coarse textures that set the book apart—those, and his animator’s knack for distinctive and expressive character design. Peter and Ernesto are very easy to tell apart. As for the other players—monkeys, dromedary, tapir, whale, and so on—they are great cartoon characters, all. Annable keeps things schematic and clear, with page layouts that vary discreetly among full-page panels and two, three, and four-panel grids (oh, but there's one glorious exception that you'll have to see for yourself). Every panel is a rectangle bounded by the same thick, ragged black line, but this sameness grounds the book and brings it to life, rhythmically. All parts work together. In short, Peter & Ernesto is a little triumph of spare, funny cartooning, and comes highly recommended. A sequel is coming. That's good news. First Second provided a review copy of this book.

OVERDUE NEWS: On May 2, the Ann Arbor Comic Arts Festival (A2CAF) and its sponsoring organization, Kids Read Comics (a nonprofit that encourages comics reading and making among young people), announced the shortlist of nominees for the 2018 Dwayne McDuffie Award for Kids' Comics. This shortlist consists of ten titles chosen from among the more than 100 comics reviewed by this year's judges: librarian and critic Alenka Figa; artist and Green Brain Comics employee Shayauna Glover, and writer and podcaster Ardo Omer. (The full list of 100-plus titles can be found at the A2CAF website.)

The Dwayne McDuffie Award for Kids' Comics began in 2015 and is awarded annually at A2CAF (formerly the Kids Read Comics Celebration). This year's A2CAF will take place on June 16-17, presented, once again, in partnership with the Ann Arbor District Library in Ann Arbor, Michigan. Note that the McDuffie Award for Kids' Comics is distinct from the Dwayne McDuffie Award for Diversity in Comics, also launched in 2015 but not specific to children's or Young Adult titles. That McDuffie Award is given out annually at the Long Beach Comic Expo. Think of the two awards as siblings! Personal PS. I got to meet and interact with the late Dwayne McDuffie just once, in November 2010, when he and his wife Charlotte (Fullerton) McDuffie visited my senior Honors class, English 492: The Comic Book Superhero. Back in the nineties, I had read quite a few Milestone Comics, a line Dwayne co-created, edited, and substantially guided, and I wanted my students to know about that. I can't remember how it is that I was able to contact Dwayne, but he was happy to come to CSUN and talk about his work. We prepared for his visit by reading the first volume of Milestone's Icon, which Dwayne had done with artist Mark Bright, plus excerpts from Jeffrey Brown's monograph Black Superheroes, Milestone Comics, and Their Fans, and by watching Season One of Justice League Unlimited, on which Dwayne had worked as producer and story editor. It was a great visit and impacted me tremendously, even though it was just a single classroom session. I won't forget it. I found Dwayne to be accessible and generous, wonderful with students, and disarmingly candid about his career, his aspirations and disappointments, and the conditions under which he worked. He was genuine and frank, justly proud of his work in comics and media, aware of its social stakes, but too wise to make overreaching claims. He registered his frustrations openly, honestly, but in a way that was never acrid or dispiriting. His sheer intelligence and enthusiasm held the room, and it was then that I realized that Dwayne was, no exaggeration, a genius, a true prodigy and polymath. My students were thrilled and enlightened, and many took the opportunity to speak to him personally. When Dwayne died suddenly about three months later, several of them contacted me about it; they were stunned. I think we were all a bit crushed. I fondly remember going to dinner afterward with Dwayne, Charlotte, and my fellow scholar Adilifu Nama (Super Black). The conversation was stellar, and a new world, or new angle onto comics, opened up to me. I think Dwayne McDuffie would be proud to see the awards created in his name, and I can't think of a better name for them. Readers, please consider donating to The Dwayne McDuffie Fund to help establish a nonprofit to award academic scholarships to diverse students and to keep McDuffie's legacy going.

NEWS! As I was reviewing 5 Worlds: The Cobalt Prince (see yesterday), I noticed, on the back cover, a logo that was new to me:  While Random House Children’s Books has already published a number of graphic novels, I hadn't seen this logo before. Today I learned why, as RHCB officially announced Random House Graphic as their new graphic novel imprint! Although Random House Graphic is not expected to launch until fall 2019—i.e. the first books developed specially for the imprint are not expected until then—Random House already appears to be telegraphing its intentions (though it's not clear exactly how RHCB's graphic novel backlist, including 5 Worlds, will mesh with the new imprint). A press release I received from RHCB this morning states that Random House Graphic will launch in fall 2019 with titles for children and teenagers and a combination of literary and commercial works. Random House Graphic will hire a team to be solely dedicated to the creation and promotion of the imprint’s titles, and for outreach and advocacy within the industry and direct-to-consumers to increase readership. The most exciting part of this news, to me, is that Gina Gagliano will be heading that team, as the new imprint's publishing director: Gagliano is a leading figure in children's and YA comics publishing. As part of the First Second team since that company's launch in 2005—most recently as First Second's Associate Director for Marketing and Publicity—Gagliano has been responsible for building connections between graphic novel publishing and diverse librarians, literary professionals, and teachers (myself included). A bittersweet note of parting on the First Second blog (from Mark Siegel, Editorial & Creative Director, and Calista Brill, Editorial Director) describes Gagliano as one of the "transformative factors" behind the "unfolding comics renaissance in America," and that's not just hype. Gina Gagliano has been a marketer-with-passion and a veritable force. Anyone who has spent even a little time talking with her has a sense of her expertise in children's literature, comics, and publishing. (Speaking personally, I'm a children's literature teacher of many years, but when I talk to Gina I feel like I should be taking notes, because her knowledge of that field is vast and detailed, and she often recommends books that I know little or nothing about.) First Second has been extremely fortunate to have Gagliano on its team, as she combines expertise in children's books with dedication to independent comics and the artist-driven side of comics culture. Her work as an event organizer (for the Brooklyn Book Festival, BookExpo, the Women in Comics collective, and the Toronto Comic Arts Festival) has made her a very respected figure in both mainstream and small-press publishing contexts. A fount of information and a tireless connector of people, Gagliano represents a living link between comics cultures and one of the best examples of a comics pro who has helped the graphic novel thrive in the book trade. In short, RHCB has made a wise choice. As publishing director of Random House Graphic, Gagliano will report to RHCB Senior Vice-President, Associate Publisher, Judith Haut. Quoted in the press release, Haut says, “It is a truly exciting and important time of growth for comics and graphic novels within the kids' market, and we see a distinct opportunity to reach even more readers. We are thrilled to have Gina, with her creativity, expertise, and passion for the medium, at the helm of our new venture.” Over at Publishers Weekly, Calvin Reid has full details. Here's a notable passage from Reid's article: ...Gagliano called it “too early” to specify the ultimate size of the list or the size of the staff she will assemble. But she emphasized that the imprint will hire "editors, designers, and publicists," and will focus on “all genres and all age categories. Kids need to grow up with graphic novels and publishers need to provide a complete reading experience. We need to add to the breadth of the comics medium in order to transform the U.S graphic novel market.” Hear, hear. I look forward to what Random House Graphic will bring.

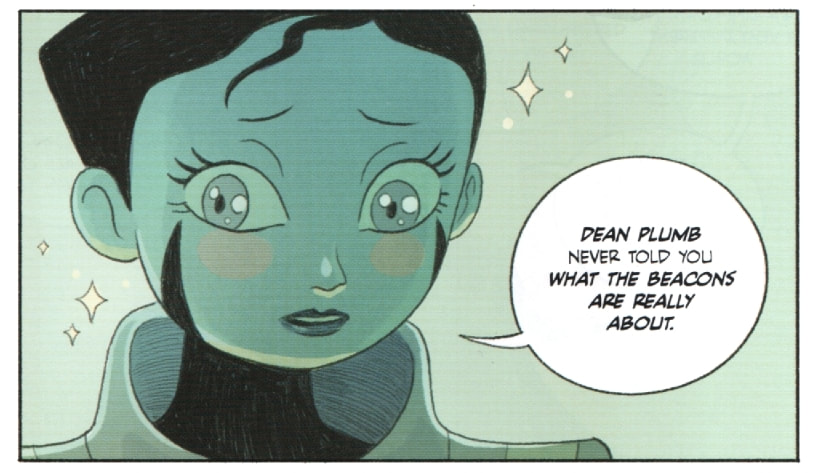

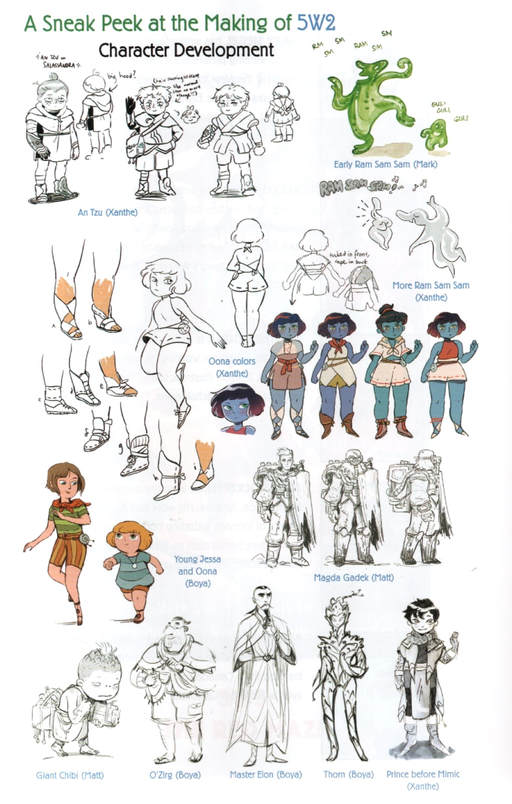

5 Worlds: The Cobalt Prince. By Mark Siegel, Alexis Siegel, Xanthe Bouma, Matt Rockefeller, and Boya Sun. Random House, May 2018. Paperback: ISBN 978-1101935910, $12.99. Hardcover: ISBN 978-1101935897, $20.99. 256 pages. Epic fantasy is a balancing act. On the one hand, its make-believe settings tend to be rule-governed and to strive after internal consistency, as if some kind of voluntary constraint were needed to hem in and discipline the pure exercise of fancy. We have to know that the characters, however magical, won't be able to do just anything they please, and that the worlds won't simply change in mid-story to suit the storyteller's whims (anyone who has ever played Dungeons & Dragons with a very whimsical DM knows how annoying that can be). Tolkien's Middle Earth has set a standard: that high fantasy worlds are to be approached with something like the self-discipline of historical fiction, even if that kind of discipline belies the very term fantasy. On the other hand, epic fantasy series, as they sprawl, often reveal new things about their worlds that shift the terms of our understanding. They elaborate, giving us more and more backstory that impinges on, or changes the stakes of, the story we're reading. Multi-volume fantasies, as they ravel out, tend to disclose (or discover) more about origins or antecedent conditions, uncovering deep foundations that may generate new problems. Even Tolkien, who crafted a history of Middle Earth before he publicly shared that world, famously said that The Lord of the Rings "grew in the telling," which I take it means that the book (ultimately trilogy) ended up drawing in more and more of the mythic backstory as he had privately envisioned it. Of course, there are also epic fantasy series written without the same strict dedication to consistency: say, Zelazny's Amber, with its odd, shifting rules. Such shifting or feinting may betray Tolkien's disciplined mode of high fantasy, but I confess I enjoy twisting, ramifying plots that reveal more of a world to me, even when the twists undermine what I thought I knew about the world at first. Consider the way Rowling's Harry Potter turns out to be a multigenerational saga set in a world more layered, and corrupt, than the first book shows, or the way Le Guin’s Earthsea, in its later books, dismantles its own patriarchal foundations, or the way Jeff Smith's Bone, in the seventh-inning stretch, gets more tangled and complex. In a satisfying fantasy epic, we will come to believe that all the complications were foreordained and fit perfectly. Besides self-consistency, then, I do enjoy the continual deepening of fantasy worlds. I bet a lot of readers do. As we travel the worlds, we learn, even as the heroes do, how complex the worlds truly are. That, I think, is the effect that 5 Worlds is going for. 5 Worlds, a collaborative graphic novel series that launched last year, does not quite persuade me that everything has been worked out, or that everything fits. Its cluster of worlds is complicated, even baroque, yet its plot is a breathless, rocket-propelled blur. I reviewed the first volume, The Sand Warrior, here recently, and complained that the tale suffered from tangled plotlines, a frantic pace, and too much downloading of mythic backstory. The second volume, The Cobalt Prince, is due out this week, and guess what? It has all those same qualities. The Cobalt Prince does not "solve" the "problems" of The Sand Warrior, and there are moments where its storytelling gets muddled. However, the book is splendidly imaginative, enough so to make its problems into virtues—which is to say that I'm glad to be revisiting 5 Worlds and exploring its universe. There's a lot going on here, plot-wise, and the book is a delirious exercise in graphic world-building. Thankfully, it remembers to round out and humanize its characters as it goes, and so attains a poignancy that the first volume lacked. If The Sand Warrior seemed promising, The Cobalt Prince is grand. By way of recap (here I'll crib from my first review), 5 Worlds is a science fantasy co-scripted and designed by cartoonist Mark Siegel and his brother Alexis Siegel and then further designed and drawn by three other cartoonists, Xanthe Bouma, Matt Rockefeller, and Boya Sun. Its plot revolves around an ecological catastrophe that threatens five rival yet interconnected planets. These are Mon Domani, the so-called Mother World, and her four satellites, each with a distinctly different culture. All five worlds are drying out and dying of heat death. Per an ancient prophecy, this disaster can be averted by relighting the long-dormant "Beacons” on each world, but not everyone believes the prophecy. Rivalry among the worlds gets in the way of cooperative problem-solving, and a shadowy adversary known as the Mimic (a sort of Dark Lord) exploits this rivalry in order to sow invasion and war. Our heroine Oona, an unfledged “sand dancer” of Mon Domani, seeks to relight the Beacons and stop the Mimic, with the help of a resourceful urchin named An Tzu and a sleek android called Jax. The first book centered on Mon Domani, but The Cobalt Prince moves on to other worlds: Toki, home of the despised, racially Othered "blue-skins," and Salassandra, home to diverse religious orders. Though Toki is the main theater of action, the plot caroms from place to place. When first I saw The Cobalt Prince, I noted Jax's absence from the cover—and sure enough Jax gets sidelined along the way, as if his story were one too many for this book. A plethora of new characters more than fills his space, and The Cobalt Prince becomes a roll call of unfamiliar names assigned to familiar archetypal roles: Master Elon, a mentor and outlaw; Ram Sam Sam, a cute ectoplasmic critter; O'Zirg, a shopkeeper; Anselka, a healer; and Magda, another mentor, this one a Master Yupa or Obi-Wan type who possesses essential knowledge. These figures become helpers or donors to our heroes (in folklorist Vladimir Propp's sense). They also bring new info, as, in good fantasy fashion, The Cobalt Prince dives into fresh elaborations and disclosures. So, even as this second book explains and solidifies things that happened in the first, it also changes the terms of the first, complicating what was already tricky. Along the way, it changes how we think of Oona (and how she thinks of herself) and makes Oona's sister Jessa, a morally ambiguous figure in the first book, into the linchpin of the plot. The sisterhood of Jessa and Oona turns out to be this book's core. Narratively, The Cobalt Prince, like The Sand Warrior before it, is a mixed bag. On the plus side, the book's elaborations are emotional as well as clever, giving it more gravity than its predecessor. Also, I like the way its plot presses on the issue of racism as both personal animus and systemic oppression. In this story, distrust and division are keyed to skin color and culture, and at times racist hatred or fear threatens to misdirect our heroes. The challenges of transcultural understanding lend the frenetic, pinballing story greater depth. However, some of that subtlety gets fumbled along the way to a grand finale: a gathering of forces that, in its rigging, reminds me of The Hobbit's Battle of Five Armies, though sadly it comes across less clearly. The book, finally, stacks up too many plot points at once. A frenzied fight between giant, godlike avatars is particularly confusing, as those beings are possessed first by one side, then by the other, blurring the action's meaning. I had to reread some pages two or three times to understand what was happening, to whom, and why. When I finally did "get" it, it was rather glorious, but on first reading I was a bit lost. An anticlimactic but necessary "epilogue" does the work of sorting things out and springboarding readers onward to the next volume. I know I'll be there, waiting to see what complications the plot delivers next. Like its predecessor, The Cobalt Prince is beautifully designed, drawn, and colored, a rapturous outpouring of images. The five-person 5 Worlds team continues to be a collaborative miracle. The book wears its visual influences on its sleeve: a temple scene on Salassandra recalls Moebius; a chase scene involving starships and an "escape pod" cannot help but evoke Star Wars. Miyazaki looms large: treks through a post-apocalyptic "wasteland" echo the opening of Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind, while the final battle invokes Princess Mononoke's giant Forest Spirit but also its sense of ecological renewal, as the dead wasteland blooms green again. 5 Worlds, then, is frankly an exercise in allusion and synthesis. The reason I not only tolerate but savor these familiar elements is that, against all odds, the 5 Worlds team makes everything seem of a piece visually. 5 Worlds continues to be a grand experiment that seems ever in danger of flying off the rails. I hope the books to come will slow down, find their feet narratively, and deliver their action more clearly. I look forward to seeing how the team's world-building and piling-up of ideas comes together as an epic whole. Will everything fit perfectly? Of course I can't say yet, but the journey is head-spinning. Random House provided a review copy of this book.

|

Archives

June 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed