|

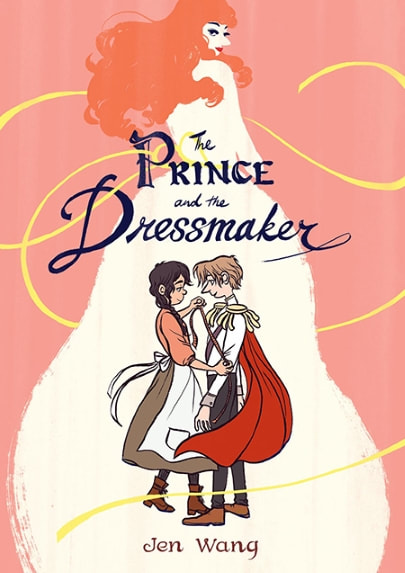

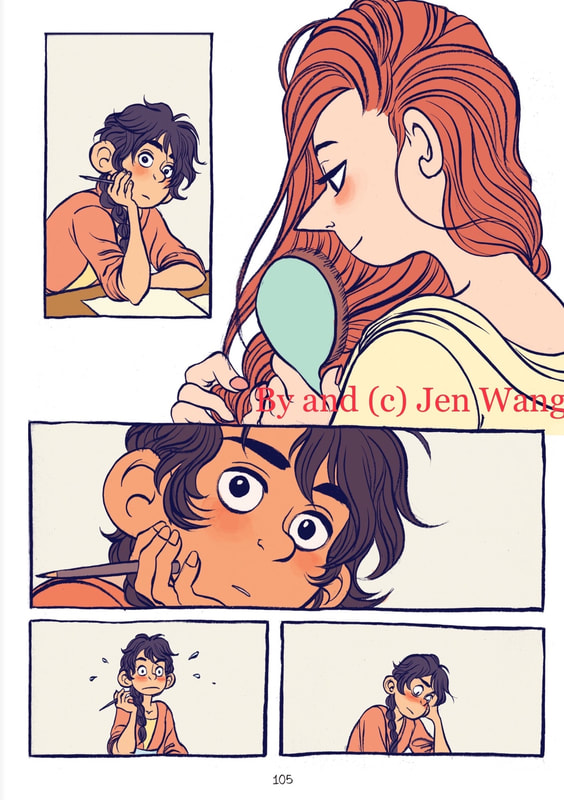

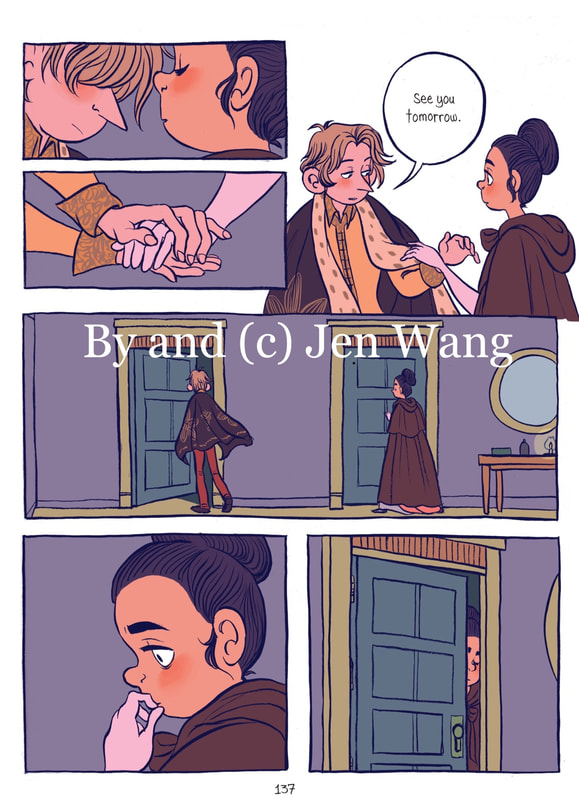

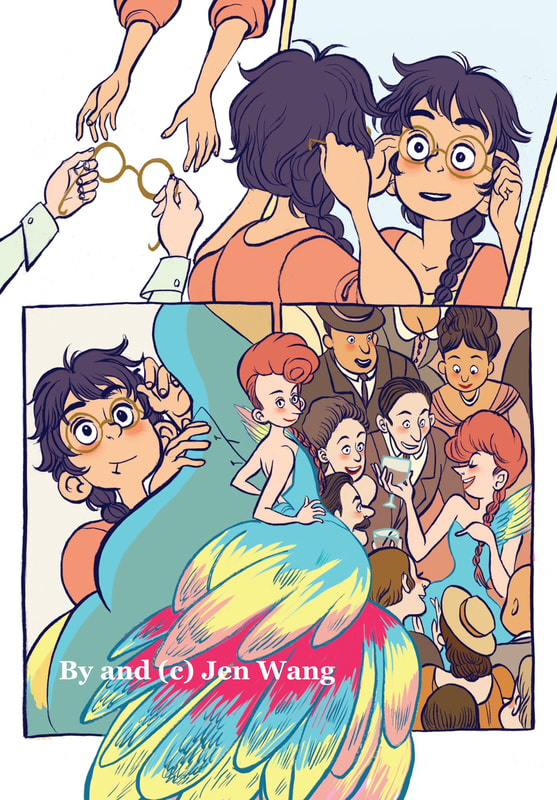

The Prince and the Dressmaker. By Jen Wang. First Second Books, February 2018. ISBN 978-1626723634. $16.99. (New to KinderComics? Check out our introductory post!) The Prince and the Dressmaker, Jen Wang’s new graphic novel, is her third, following Koko Be Good (2010) and In Real Life (2014). All her books have been well reviewed and admired, but this one is likely to be remembered as her breakout, deservedly so. A genderbending YA fairy tale romance set in a make-believe Paris on the cusp of modernity—a Belle Époque Paris with haute couture and department stores but no trace of Industrial Age grime—The Prince and the Dressmaker tells a tender story of nonconformity, the delicate art of public personhood, and desire. I especially like the way it does not editorialize about desire but instead evokes it, often wordlessly, hauntingly—without moralistic signposting and with a florid style that captures the flush of recognition and the confusion of feelings that desire can bring. A marvel of fluid, expressive cartooning, this book takes a fairly shopworn notion, that of the progressive fairy tale (often a go-to genre for feminist, gender-nonconforming subversiveness), and fills it with startling new life. It gives fresh evidence of Wang’s deftness and grace as a comics artist: her characters live, her rhythms draw this reader breathlessly in, and her pages pop. In short, this is artful work, fraught and emotionally daring, ultimately affirming, and, well, ravishing. As the above cover hints, The Prince and the Dressmaker is a prince-and-pauper fable about a process of artistic co-creation: the collaboration between a hard-working seamstress and designer, Frances, and a furtively cross-dressing prince, Sebastian, for whom Frances makes dresses. Sebastian endures his parents' attempts to marry him off to this or that young noblewoman but really only comes alive when he can venture into the world incognito, as Lady Crystallia: a fashion plate and the magnet of every elegant young lady's attention. It is Frances's skill and hard work that transform Prince into Lady; essentially, Crystallia is their joint work of art, with Frances as designer and Sebastian as model. Their clandestine partnership grants Sebastian a chance to live more freely, though only for brief, risky episodes, and Frances a chance to practice her art, but only anonymously. It's a match made in Heaven—or isn't, since each can only enjoy the work of creating Lady Crystallia by hiding or disavowing who they are. Sebastian remains closeted, and Frances remains unknown and unsung, denied the opportunity to take her skills public and fashion an autonomous career. The story tugs at this problem, and one other: that of unacknowledged, perhaps confused, desire. That is, The Prince and the Dressmaker is a love story as well as a Künstlerroman. The novel's plot is not especially devious or complex, and stakes out familiar territory. I'm reminded of feminist and queer-positive fairy tale books such as The Paper Bag Princess and King and King; feminist and queer-positive fairy tale comics like Castle Waiting, Princeless and Princess Princess Ever After; and the cross-dressing traditions of shojo manga (here slyly inverted) as well as manga's more recent explorations of transgender experience (notably, Shimura). Further, the faux-European setting, at once antique and yet salted with anachronisms in speech and manner, recalls the vague storybook Europe of Miyazaki. Familiar things, as I said. What Wang has accomplished here, though, does not boil down to a bald set of thematic or genre conventions; she wins on the details, which are myriad and lovely. The story comes across delicately, with expressive body language and telling grace notes of observation, and thankfully without intrusive narration or didactic underscoring. Frances and Sebastian have next to nothing in the way of backstory, but they remain distinct, visually quirky, well realized characters: Frances a mix of self-sufficiency, ambition, self-deprecation, and inquisitive desire (she looks at things very intently, yet sometimes bashfully looks away); Sebastian a dutiful, conflicted son as well as a lady (ostensibly genderfluid rather than trans), at times selfish or too caught up in his own need for safe hiding, at other times frank and courageous. Frances is willing to help Sebastian, and vice versa, because of mingled kindness, affection, and self-interest—and the willingness of each is tested. Both endure moments of terrible emotional exposure, betrayal, and bewilderment. Wang works the familiar turf beautifully. What I like best in The Prince and the Dressmaker is Wang's way with silence. Of the books 250-plus pages, almost a fifth are wholly wordless, and the great majority of spreads in the book include wordless panels or passages. The novel is entirely unnarrated, like a fast-moving film, but the delight Wang so clearly takes in rendering characters—and, my gosh, couture, in great, swooning, rapturous fits—roots the work in the pleasures of drawing and of comics. Some of the wordless passages dilate on brief sequences of action, catching and expanding small moments; others compress time, montage-style, whisking the characters through hours or days with giddy speed. The minimal wording and lavish drawing together convey ambiguous and conflicted emotion beautifully; witness pregnant moments of observation or reflection like this: The first example above seems, to me, to flirt with Frances's confusion about her own desires, or perhaps simply with the recognition of Sebastian's androgynous beauty. It says volumes. Both the first and second example show one of the things Wang is so very good at: emotional irresolution and the weight of the unspoken. Throughout the book, pairs of panels will hint at subtle interchanges and abashed feelings: All this happens against the backdrop of gorgeous pages, typically airy and free, generous with open space, against which panels and rows of panels appear to float. Bleeds are common: characters and scenes very often go right to the cut edge of the leaves (and implicitly beyond). Indeed Wang will often highlight a critical pause or loaded moment by placing a character at the bottom edge of the page so that the figure bleeds off, as if to hold the eye momentarily before the page turn. In any case, the pages are consistently dynamic without being attention-begging; Wang has a wonderful layout sense to complement her supple and expressive character drawings. No two pages are the same. I could go on about Wang's diverting artistry. It's the sort of thing I love to note: the kinetic freedom of her drawing; the exactness of the movements and expressions captured by her pencil and brush; the ravishing colors; the breath and pulse of the pages. But I think the things that really matter in The Prince and the Dressmaker are the narrative surprises and payoffs (er, these might qualify as spoilers, though I'll try to be vague): the cruelty of Sebastian's eventual exposure; the tender about-face that follows, upending cliched father-son dynamics; the delicious queering of a fashion show that serves as a sort of climax; and the final expression of the unexpressed that is, for me, the book's real climax. Of course all this is expertly cartooned, at the precise point where artistic discipline yields freedom. Yet it's Wang the total storyteller, the writer-artist, who finally gets to me. It's the complete package that made this jaded old reader daub his eyes. In sum, Wang has hit a new high. The Prince and the Dressmaker is very, very good comics, and puts the fairy tale tradition to wise ends. It envisions a better, braver world, one in which loving self-expression and artistic co-creation happily overleap ideological hurdles, setting more than one spirit free.

0 Comments

|

Archives

June 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed