|

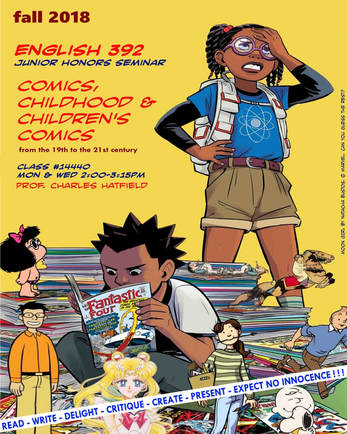

(The following statement opens the syllabus for English 392: Comics, Childhood, and Children's Comics, a course I am now teaching at CSU Northridge. English 392 launched on August 27, 2018, and we are at, roughly, mid-term. Regular KinderComics readers will recognize this post as one in a continuing series on teaching.) Did you know that Scholastic—publisher of Harry Potter, Captain Underpants, and The Baby-sitters Club—is also America's number one publisher of new, English-language comics? Not Marvel. Not DC. Scholastic. In fact, we are in a Golden Age of comics for children and young adults, in the form of the graphic novel. For about the past decade, graphic novels have been booming as a young reader's genre. Today, diverse publishers and imprints are competing to put graphic novels in the hands of children and teens: Graphix (Scholastic), First Second (Macmillan), Amulet (Abrams), Random House, TOON Books, Papercutz, BOOM! Studios, Farrar, Straus and Giroux BYR, Flying Eye Books (Nobrow), and others, including brand-new or forthcoming imprints CubHouse (Lion Forge), Yen Press JY, and even DC's soon-to-launch DC Zoom and DC Ink. In short, something interesting is going on. Who could have predicted this trend fifteen years ago? Comics, historically, have been a disreputable medium, branded as "objectionable," even as a threat to childhood, learning, and literacy. Further, the field of academic children's literature criticism (launched in the 1970s) has been so averse to comics that for decades it downplayed or ignored the form. The current interdisciplinary field of childhood studies has produced little work on comics. Even the field of comics studies, which has been exploding in the twenty-first century, has been so eager to attain legitimacy and "adulthood" (in terms defined by adult literature) that it has stinted research on children’s comics. Until quite recently, few scholars have felt the need to examine the intersection of comics and childhood. Yet comics have been central to the literacy stories, and reading lives, of millions of children the world over. Moreover, children's comics include many of the most influential comics ever published. Young readers have been the target audience of the most successful comics ever made—and those have been very successful indeed, in terms of profit, cultural influence, and deep connections made with readers. Comics for children are not new, even if we are now thinking of them in new ways. Many national cultures, from the Americas to Europe to Asia, have sustained long traditions of children's comics and drawn iconic images and characters from those comics (How can one understand postwar Japan without the manga of Tezuka, or contemporary France without Asterix?). In the United States, millions of readers young and old read comic strips in newspapers throughout most of the twentieth century, and the comic book, born in the Depression era, mushroomed by the end of the forties into an industry that sold tens of millions of magazines every month, most of them to young people. If comic books were disreputable, they were also hugely popular and influential. If many of us have almost forgotten that era, still it lives on, implicitly, in today's conversations about the graphic novel and children. Nowadays we see in comics the seed of a new visual literacy, complex and multimodal, but have the old fears gone away? Simply put, comics for children is a vital but still-obscured topic crying out for critical study—and that's what our English 392 class is all about. We will study the contemporary graphic novel as a children's and YA publishing phenomenon, and trace how and why this renascence has come about. In addition, we will consider (though alas only too briefly) the troubled history that lies behind this trend. What social, cultural, and educational changes have transformed the once-disreputable comic book into the graphic novel of today? What dynamics of power and cultural legitimization (or delegitimization) have changed the status of comics in our culture? To what extent has comics' reputation as illegitimate persisted, despite the current boom in children's comics? Together we will read articles and book chapters in children’s literature and comics studies, plus a range of children’s comics, from pioneering strips (e.g. Peanuts) to comic books to, most especially, contemporary graphic novels by authors such as Raina Telgemeier and Gene Luen Yang. As we work together, each of you individually will be able to find your own areas of interest and dig more deeply. Expect to present in class, i.e. lead class discussion, at least once during the semester; to pursue self-directed research responsive to your own interests; and to craft a final seminar paper roughly 10 to 12 pages in length. Expect several guest speakers as well!

0 Comments

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

Archives

June 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed