|

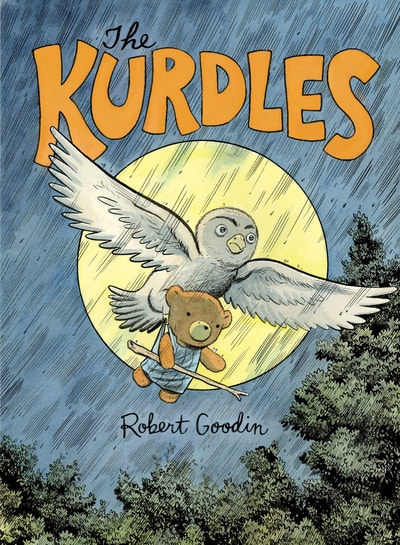

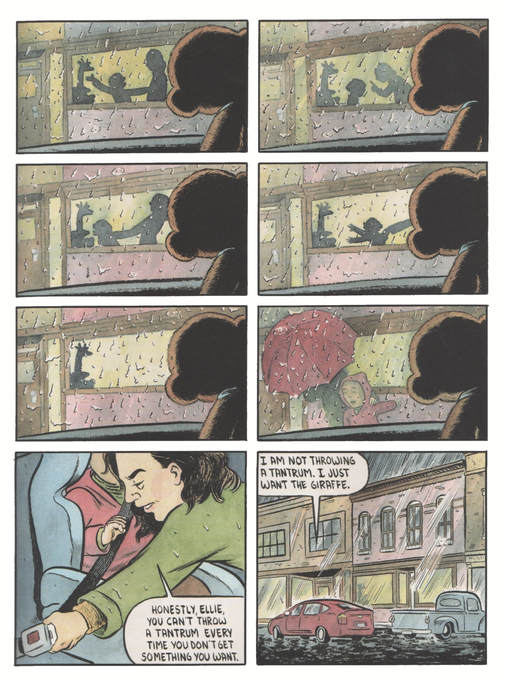

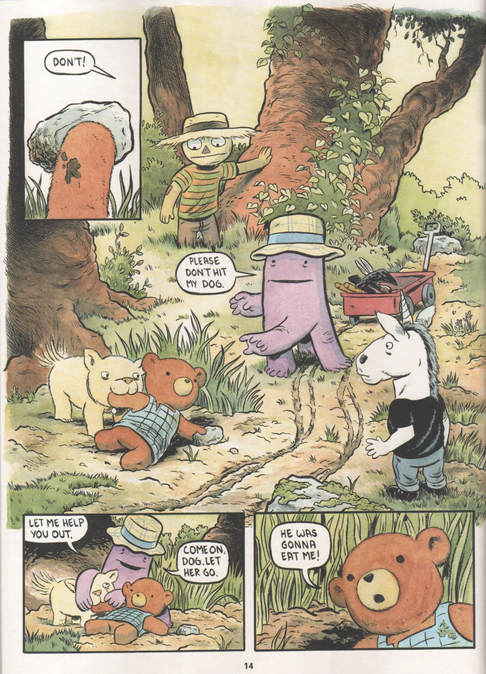

The Kurdles. By Robert Goodin. Fantagraphics, 2015. ISBN 978-1606998328. Hardcover, 60 pages, $24.99. A teddy bear gets lost, or discarded, by a child—that's how The Kurdles begins. Will she, Sally Bear, be reunited with "her" child"? The plot feints in that direction: a common story problem for child-centered, toys-come-to-life tales. Think Toy Story, and the nostalgia those films invoke: they're all about a kidcentric microcosm in which toys, though sentient, depend on the love of a child to give their life meaning. But The Kurdles doesn't end up telling that kind of story; instead it pulls a narrative bait-and-switch and becomes a sort of anti-Toy Story, one in which no Andy or Christopher Robin is needed to confer life or purpose on the lost teddy. Sally finds herself in Kurdleton, a woodland retreat, in the company of other critters: a land-going pentapus (think octopus with just five limbs), a unicorn in a tee shirt and jeans, and a scarecrow that evokes Baum's Oz (with perhaps a touch of Johnny Gruelle's Raggedy Andy too). This klatch of strange beasts also recalls, for me, Tove Jansson's Moominland, or Enid Blyton's Faraway Tree series. There's that same sense of utopian, slightly anarchic domestic community, of a little world apart from our own with its own matter-of-fact logic (or no governing logic at all). This is home to The Kurdles, and where the story wants to stay. With The Kurdles, then, cartoonist Robert Goodin has fashioned a fantasy world that owes a great deal to the history of children's books. Oddly, though, the book seems out of step with almost anyone's idea of a children's graphic novel today. The Kurdles does kids' comics the way, say, Gilbert Hernandez and co. did with Measles (1998-2001), or the way Jordan Crane did with The Clouds Above (2005)—that is, eccentrically, with seemingly no regard for the conventional wisdom about what today's children need or want. I suspect that's part of the reason why I like The Kurdles so much. Certainly I like this kind of idiosyncratic world-building in comics, regardless of intended audience. I expect that The Kurdles' best audience will be comics-lovers with a feel for the medium's history and an appetite for the upending of traditional story motifs. Me, I like it for the quirks and for the way it refuses to make sense. The book's opening depicts an argument between a human mother and child, as seen from a distance by a teddy bear. We don't yet know that the bear is Sally, or that she's alive: Sally's autonomous life is revealed only gradually, slyly, in the pages that follow, after she is parted from this human family. (The sequence in which she finally transitions from inert doll to living, moving creature is so delicious that I'm not going to show it here.) It takes even longer to reveal Sally's capacity for speech—which we realize about the same time as her capacity for self-defense, even violent resistance. What brings Sally fully to life is her arrival in Kurdleton, and the appearance of Kurdleton's other bizarre residents: What follows is a shaggy dog story in which a sickly house (the sum total of living quarters in Kurdleton) becomes anthropomorphic and then, as if delirious with flu, begins to sing sea shanties as if it were a drunken sailor. Yes, you read that right. The other denizens of Kurdleton set out to find a cure, but I'll say no more. Suffice to say that the Kurdles have no origin stories, no explanations for why they live in this place, nor any backstory that anyone feels obliged to ask about. Only Sally, of all the characters, has the rudiments of an "arc" (and even hers gets rerouted). What's more, the Kurdles don't have the familial structure of Jansson's Moomins, or the love of a human child, à la Milne's critters in the Hundred Acre Wood, to bring them together. They're just weird, and live in a weird place, where their essential weirdness needs no excuse. That's The Kurdles. The Kurdles is also eccentric visually. Lushly drawn and watercolored, it's organic, i.e. emphatically pre-digital, in look, with a fully realized, woodsy environment. Boldly brushed contours coexist with dense hatching, and the art is texture-mad. Color-wise, Goodin's pages depart from the Photoshop norm of most children's graphic books, and I found myself looking for the rough edges where linework and watercolor met (though Goodin is so crisp that I hardly ever found them). The work is old-fashioned and sumptuous, illustrative and humanly accessible to these middle-age eyes. Far from the clear-line, flat-color style so redolent of children's comics (the bright Colorforms look that bridges everything from Hergé to Gene Yang), The Kurdles is beautifully scruffy, or scruffily beautiful. It's as if Goodin, whose work I know mainly from TV animation and his erstwhile Robot Publishing venture, is determined to make The Kurdles a space of retreat from all of his other doings. The Kurdles is blithe, blunt, and unsentimental, sometimes startling, often deadpan-hilarious: a world and logic unto itself. I dig it. I do worry, though, about the commercial prospects for work like this, i.e. work that carries with it a wealth of history and memory but hails from outside of the children's publishing mainstream. This is the sort of work that has flourished fitfully here and there under the aegis of the direct market and within a small-press, underground aesthetic (I think for example of Neil the Horse, c. 1983-88, by Katherine Collins, formerly Arn Saba). Fantagraphics has announced a Kurdles Adventure Magazine for this summer, and reading more Kurdles would do me good, so I can only hope. This is too weird and wonderful a world to lie fallow. Fantagraphics provided a review copy of this book.

0 Comments

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

Archives

June 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed