|

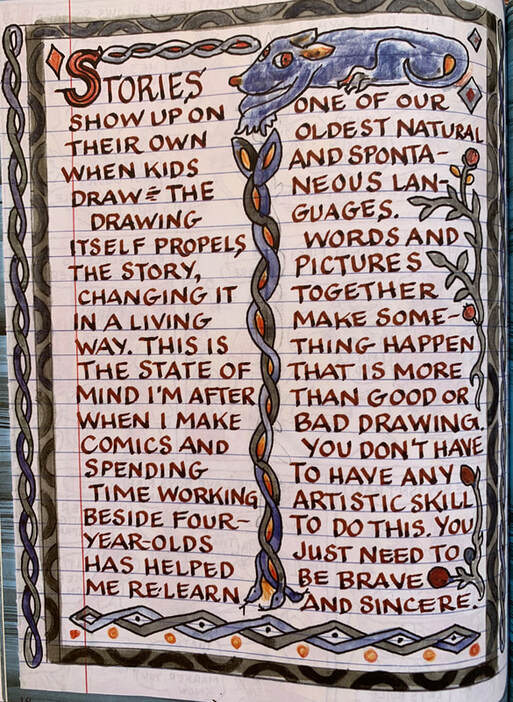

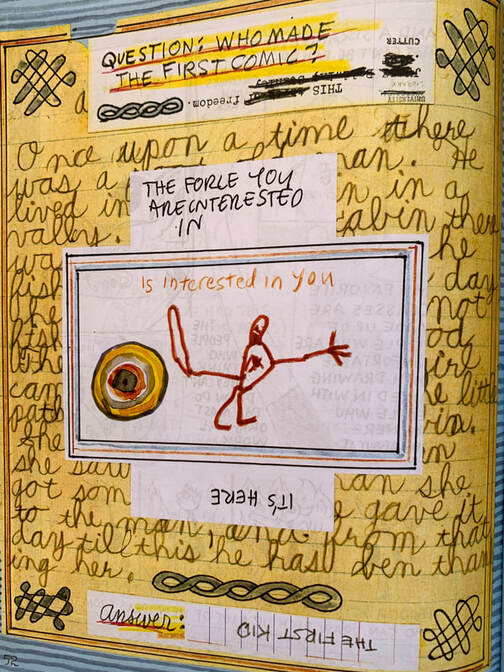

Tuesday night’s conversation between Lynda Barry and Chris Ware (at the Aratani Theater in downtown Los Angeles, organized by Skylight Books) touched on childhood again and again. Both artists shared pictures or artifacts from their childhoods and recounted formative childhood experiences: Ware recalled a life-changing friendship he had as a young boy with another introverted, comics-loving schoolboy, memories of which continue to fuel his work (particularly his new graphic novel, Rusty Brown). Barry expressed her delight at working with four-year-old artists as well as university students, and evoked her girlhood experience of watching a troubled young uncle draw obsessively (a story movingly told in her new book, Making Comics). Both artists stressed honesty and spontaneity over scripting or planning, and invoked the unselfconscious narrative drawing of children as an inspiration. Barry, animated, disarming, and often hilarious (as ever), showed photos and videos of young kids drawing and learning, her comments suggesting an almost Wordsworthian romantic regard for children’s untrammeled creativity (though mixed with a matter-of-fact acceptance of the terrors that kids’ stories so often uncover). Ware, woefully self-deprecating (as usual) but also articulate and funny (as usual), spoke of memory, of reinhabiting remembered spaces and using comics to move through recollected time. It was one hell of a chat. Ware began his comments by recalling how Barry inspired him, early on. He was clearly in awe of Barry and delighted by her irrepressibility. Barry readily drew him (and the audience) out, and into deep conversation. Aesthetically, the two artists would seem an odd match, and frankly I think their works differ fundamentally despite the mutual admiration they projected during their talk, but as a conversational tag team they were delightful. The evening gave me a lot to think about—most of all comics’ debt to memory and the mysteries of narrative drawing. (I only regret that we couldn’t spend hours hanging around afterward, sharing our impressions of the talk with some of the many fans and artists there--a big and enthusiastic crowd. I think there were several people in the audience that I know, but we couldn’t seek them out, as the night was wearing on and we had an early morning to get ready for.) Though Ware’s comments about spontaneity in writing and drawing resonated with Barry’s, I confess I don’t see him working in anything like the same vein. He says that these days he works from page to page, instinctively, without script, but some architectonic notion of form still seems to guide him, and his work remains compulsively crafted in ways that veer far from what Barry celebrates in Making Comics. Indeed, Ware invoked as points of reference, or aspirational guides, such designing literary figures as Joyce and Nabokov, and expressed his admiration for big books that “sprawl” (but that also, I would add, impose global structure through myriad devices). His comments revealed how Rusty Brown is deliberately shaped with an overall sense of form: at one point he likened his new book’s structure to that of a water molecule, or a snowflake forming, and explained how the book’s removable jacket, which charts or anticipates the various narratives contained within, would be complemented by another such jacket when, years from now, he completes the novel’s anticipated second volume (!). So, he is already thinking about design conceits that will contain and contextualize whatever he comes up with. In light of comments like these, I take Ware’s comments about spontaneous invention with the proverbial grain of salt—I don’t think his meticulously crafted surfaces jibe with Barry’s ethos of unlocking creativity through drawing-as-process. I also think that Barry’s theorizing about narrative drawing (“There was a time when drawing and writing were not separated for you”) is really onto something, whereas Ware’s theories about narrative drawing often seem belied by the nature of his own work. For example, when Ware says that the functionality of a drawing matters more than its beauty or polish, I don’t see that borne out by his (often gorgeous, always pristine) pages, and I know many readers fetishize Ware's craft. Yet when Barry says similar things, I see a clear connection between her theory and her pedagogical practice (though I find her pages just as beautiful, in a much different way). In general, I tend to take Ware’s theoretical positions as somewhat at odds with what I see in his work, but Barry, I think, has truly embraced a romantic position about cartooning as demotic and open to all (“You don’t have to have any artistic skill to do this. You just need to be brave and sincere”). The obvious contrast between their respective styles of work, however, did not stop them from finding points to share and admire. Again, Ware seemed grateful to be sharing a stage with Barry, and, I thought, caught some of her energy, while Barry was, in effect, a gracious and delightful host. Despite the manifest differences between their work, I was fascinated to see both of them harking back to childhood as a wellspring of inspiration. They did this in different ways, of course. When asked by an audience member what they would say to their childhood selves if they could go back in time, they had very different answers: Barry said she would assure her younger self that it would all work out fine, that the struggles would definitely turn out to be “worth it." Ware, on the other hand, said he didn’t think he could reassure his younger self because, essentially, his work feeds on sad and anxious memories—that is, reassurance would take away the impetus or subject matter of much of his art. That right there speaks volumes, I think, about their differences in temperament and focus. PS. I’ve been reading Barry’s Making Comics with great interest and hope to review it here. It’s an extraordinary book, one that will influence my teaching going forward (as indeed some of Barry’s previous books already have). This is turning out to be an incredible season for new comics releases!

5 Comments

10/19/2019 06:31:27 am

A apologia for Unspontaneous invention--I felt a little like a cat whose fur is brushed in the wrong direction while reading this blog entry. I should say, however, that I greatly respect the writer and he should take these comments as a "I respectfully disagree" riposte. There is a lot to be said for spontaneous creativity, and there is no doubt that Barry has found a way to bring this out in her students and herself. But her work also involves reflection and the meticulous application of craft. Just look at her amazing hand-drawn illuminated manuscript! That's not something one dashes off using a stopwatch. Ware's work operates according to a different aesthetic, and on a different timescale. I've been thinking about how his work is the narrative equivalent of the past imperfect, or the free indirect style. The delight for me is the sudden revelations and the flashes of insight that you have to wait decades for. I really admire both artists. But the suggestion that one would compare the two, and to Ware's disadvantage, seems unfair since they after vastly different aesthetic goals. It's probably just my temperment--I'm the introverted one with the unhappy childhood. But I'm with Ware for the long haul.

Reply

Charles Hatfield

10/20/2019 12:25:30 pm

Martha, thank you for weighing in -- it's good to hear from one of the foremost Ware scholars out there! I too am with Ware "for the long haul," though I've become increasingly skeptical about his comments on cartooning (comments that obviously serve to unlock his own work but that are not necessarily gospel for all comics). You're right that it's unfair to both Ware and Barry to contrast them as this post does. Obviously, Barry's work is very carefully crafted (though I think her own theorizing about comics and images and memory tends to downplay that element). Just as obviously, Ware is indebted to Barry's comics-writing and is not being disingenuous when he expresses his admiration for her.

Reply

Charles Hatfield

10/20/2019 12:30:37 pm

PS. I think that artists often say things about art that they need to believe are true for the sake of their own work but that turn out not to be true for all artists. For example, Spiegelman or Pekar would not be very good guides for comics history as a whole; the very things that made their work possible also make them somewhat biased observers (though Spiegelman, to be fair, knows an awful lot even about comics he appears to disdain). I also think that artists sometimes espouse principles that are belied by their own work: witness, e.g., Brian Eno or David Byrne's theorizing about music. Yet they need to say such things to make their own work possible.

Reply

David Ball

10/21/2019 01:34:58 am

Thanks for the post, Charles. I'm sorry to have missed the conversation, which sounds like a lively one. I just finished Rusty Brown--with the aid of my 7yo daughter's junior gemologist mini magnifying glass, which felt like a Wareian detail--but have yet to receive my copy on Making Comics. So, doubly jealous. As different as their styles are, I tend to see Barry's and Ware's projects as aligned in many ways. More than anything, in reading Monograph and now Rusty Brown, Ware more and more for me is becoming a diarist, a recorder of quotidian life. While he looks much closer to On Kawara than Gabrielle Bell, the stakes of these projects seem very similar to me. With the exception of the dust jacket, the elaborate diagrams of Jimmy Corrigan are gone (or perhaps slipped my regard in a first reading), replaced by more of the moment-to-moment lives of his characters. I don't know if his diaries will ever be published--there are only a few reproduced in Monograph and the sketchbooks, all too tiny to read--but if they see the light of day, they'll be prodigious. I suspect Ware would say something here about both the routines and the spontaneity of daily life, a worldview I'm sympathetic to, especially as the father of young children. And having seen pages in process and boards where he's working on multiple projects at once, I'm convinced he assembles as he goes, although the cleanness of his compositions belies this composition process. All of which is to say that I take Ware at his word, though I agree, this is equally an act of the artist justifying their way of working and seeing the world. I'm excited to dig into Making Comics and seeing the relays and points of departure. And I'm eager to see smart reviews of Rusty Brown--it's been crickets thus far. Thanks so much for sharing this evening more broadly! db

Reply

Charles Hatfield

10/30/2019 12:10:17 am

Dave, thank you for weighing in! I should note that Ware mentioned his graphic diaries a couple of times, but was emphatically clear about not intending to publish them. And, yes, I do see how he could assemble as he goes; he may tunnel into each page or spread very intensely, but I should grant that there is still room for discovery and re-assembly as he moves toward larger frames of reference. I have to admit, though, that to me the diagrammatic conceits are still so very formalized that I have a hard time thinking of his GNs as diaristic. For example, the "Jordan Lint" section of Rusty uses all kinds of highly schematized, diagrammatic imagery to convey the unprocessed experiences of a newborn or infant. It's less diaristic than intensely, deliberately patterned, shaped to a highly intellectualized evocation of childhood experience. I see these conceits as organizing experience according to frames that are not so much diaristic as, well, novelistic: concerned with patterning and braiding in the long form. Hmmm?

Reply

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

Archives

June 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed