|

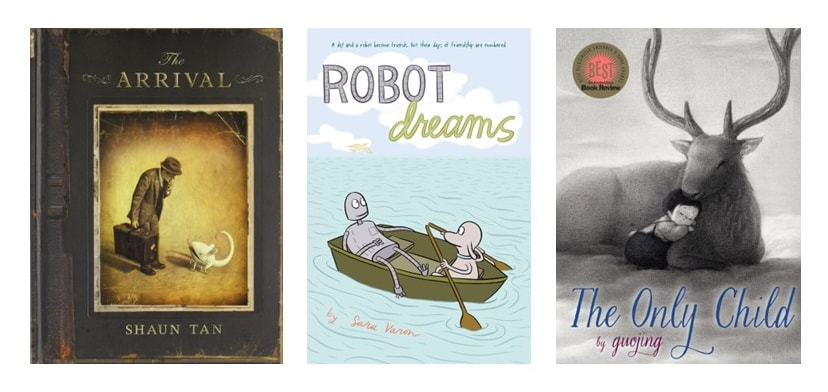

A guest post by Gwen Athene Tarbox The KinderComics Teaching Roundtable continues! Today my colleague Dr. Gwen Athene Tarbox, expert in comics and children's literature and co-editor of the essential Graphic Novels for Children and Young Adults (2017), responds to posts by me and Joe Sutliff Sanders regarding the challenges of teaching comics for and about children. This series arises from my preparations for teaching (this coming Fall) a seminar called Comics, Childhood, and Children’s Comics. Gwen, thank you for contributing your voice here! - Charles Hatfield When it comes to identifying strategies for teaching children’s comics, context matters. As Charles embarks upon the process of developing an elective honors seminar, ENGL 392, Comics, Childhood, and Children’s Comics, he knows that his students have at least some interest in comics and are probably used to researching and writing about interdisciplinary subject matter. The Department of English at California State University, Northridge frequently offers courses in popular culture, and Charles is one of a number of faculty members who integrate comics into their syllabi. Could there possibly be a downside to teaching childhood and children’s comics within a supportive academic environment? Well, not really, but as Charles tells us in his roundtable post, being faced with a seemingly unlimited set of topics and approaches at the nexus of two complex fields makes for a daunting task. Joe, a Lecturer in the Faculty of Education at the University of Cambridge, teaches in a system where students are exposed to a variety of instructors and subjects related to literature, education, and the history of education, as part of a three-year program that combines seminars with tutorials. As he explains in his roundtable post, “I have about two hours to give the students a fiery introduction to the material that will drive them to go educate themselves about the subject once I’m gone.” Many of Joe’s colleagues are interested in visual culture, as are the undergraduate and graduate students with whom he works, but the UK university system relies upon students being much more self-directed, so Joe may end up doing more of his teaching informally, in conferences with individual students. His concerns about teaching canonical texts, which are overwhelmingly male and White, should be shared by anyone who teaches in our fields, and Joe may have to rely upon handing out bibliographies and carving out an online or podcast resource for his students to ensure that they are familiar with a broad spectrum of comics texts. My own experience in the Department of English at Western Michigan University involves integrating comics into ENGL 3820, Literature for the Young Child, and ENGL 3830, Literature for the Intermediate Reader, courses that are required for elementary education majors, but can also serve as general education electives. Creative writing majors, inspired by the success of J.K. Rowling, Jacqueline Woodson, and Kwame Alexander, view 3820 and 3830 as venues for unlocking the secrets of character development or comparing how different media impact the way a narrative unfolds. However, regardless of their motivations for taking my courses, all but a few of my students tell me up front that they are AFRAID of comics—perhaps not as afraid as they are of taking Math 2650, Probability and Statistics for Elementary/Middle School Teachers… but for at least some of my students analyzing comics appears to be as terrifying as being asked to switch on their calculators. My context—preparing future teachers and aspiring authors—compels me to select texts that are frequently used in classrooms or are cutting-edge in terms of their form, and also means that many of my students are encountering comics for the very first time. Typically, I ease my children’s literature undergraduates into the study of comics by spending most of the semester focusing on visual rhetoric, first with picture books and illustrated novels and then moving on to hybrid texts such as Lorena Alvarez’ Nightlights and to films like Paddington or Coco. Then, on the first day of class devoted solely to comics, I hand out a few wordless offerings--Shaun Tan’s The Arrival, Sara Varon’s Robot Dreams, or Guojing’s The Only Child—and ask students to read them aloud. Reading aloud has become a major component of our children’s literature courses, so when students appear flustered and hesitate, it is not because they are unaccustomed to reading in front of their peers. Rather, they are hesitant because, and I give voice here to my students: “How do I know what to read first? What if I interpret something incorrectly? Do I take in the whole page first and summarize it? Or do I talk about each panel? Who is the narrator? Where is the narrator?” All of these questions lead us to a nuts-and-bolts discussion of form and content that occurs organically and is supplemented by excerpts from a variety of critical texts, including Joe’s essay, “Chaperoning Words: Meaning-Making in Comics and Picture Books” (Children’s Literature, 2013), Charles’s “Comic Art, Children's Literature, and the New Comic Studies” (The Lion and the Unicorn, 2006), and Paul Karasik and Mark Newgarden’s newly released How to Read Nancy. Since 2017, I have been working on a book, Children’s and Young Adult Comics, that will come out later this year from Bloomsbury Academic. Like Charles, I have struggled to carve out a narrow enough focus, and like Joe, I feel as if I have only a few short chapters to encourage readers’ investment in children’s comics. Writing an introductory guide to children’s comics has a lot in common with teaching children’s comics insofar as I spend as much time worrying about what I have left out as I do about what is actually on the page. Another venue that has contributed significantly to my understanding of how to share comics with my students is the Comics Alternative Young Readers podcast that I have been a part of since 2015. Working first with Andy Wolverton, and now with Paul Lai, I have had the chance to read dozens of children’s and YA comics every year and to talk about them with experts. Derek Royal, who co-founded and now runs The Comics Alternative, is another great resource whom I consult regularly and with whom I have interviewed a number of children’s comics creators, including Mairghread Scott, Tony Cliff, and Hope Larson. Finally, I was fortunate enough to co-edit Graphic Novels for Children and Young Adults: A Critical Collection (University of Mississippi Press, 2017—now available in paperback), with Michelle Ann Abate, and the process introduced me to over twenty scholars, from traditional literary critics to teacher educators to visual theorists and cultural studies experts, all of whom provide in-depth analyses of a host of contemporary children’s and YA comics. What heartens me the most, then, is that a large community is beginning to congregate around the study and teaching of children’s and YA comics. Charles and Joe, Laura Jiménez, David Low, Nathalie op de Beeck, Carol Tilley, Michelle Ann Abate, Philip Nel, and countless other amazing scholars are helping to create an ongoing dialogue about the intersection of two fields whose fortunes have often been linked, but have rarely been discussed together. And now we have KinderComics, Charles’s blog, as another important resource! (Note: this roundtable will continue in the weeks and months ahead. - CH) Gwen Athene Tarbox is a professor in the Department of English at Western Michigan University, where she teaches courses in children's and YA literature, as well as comics studies. She is the author of The Clubwomen's Daughters: Collectivist Impulses in Progressive-era Girls' Fiction (Routledge, 2001), co-editor with Michelle Ann Abate of Graphic Novels for Children and Young Adults: A Critical Collection (UP of Miss, 2017), and author of an upcoming monograph, Children's and Young Adult Comics, from Bloomsbury Academic. She has written articles on the comics of Hergé and Gene Luen Yang, on teaching comics, and on various topics related to children's literature. She is also co-host, with Paul Lai, of The Comics Alternative's Young Reader podcast, which airs towards the end of every month (www.comicsalternative.com).

3 Comments

Charles Hatfield

4/17/2018 05:00:07 pm

Gwen, I love the idea of having students read wordless comics aloud, and of using that exercise as a "nuts-and-bolts" entryway into form. That's such a great idea that, um, I am tempted to "lift" it.

Reply

Charles Hatfield

4/17/2018 07:26:46 pm

Gwen, I should clarify: I too have to assume, in most cases, that my students are encountering comics for the very first time. This is true even in intensive seminars, such as honors and graduate seminars, which are earmarked for advanced independent research. I find that the mix of students in those courses is unpredictable and that it is safest to assume little experience with comics-reading and no experience with critical comics studies. I guess that’s because in most cases my class, whichever class it may be, at whatever level, will be the only one my students have had that calls for formal academic study of comics and cartooning.

Reply

Charles Hatfield

4/17/2018 07:29:01 pm

PS. In this way, what you've described as an opening "nuts-and-bolts" strategy could be a very helpful start to 392! Thank you.

Reply

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

Archives

June 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed