|

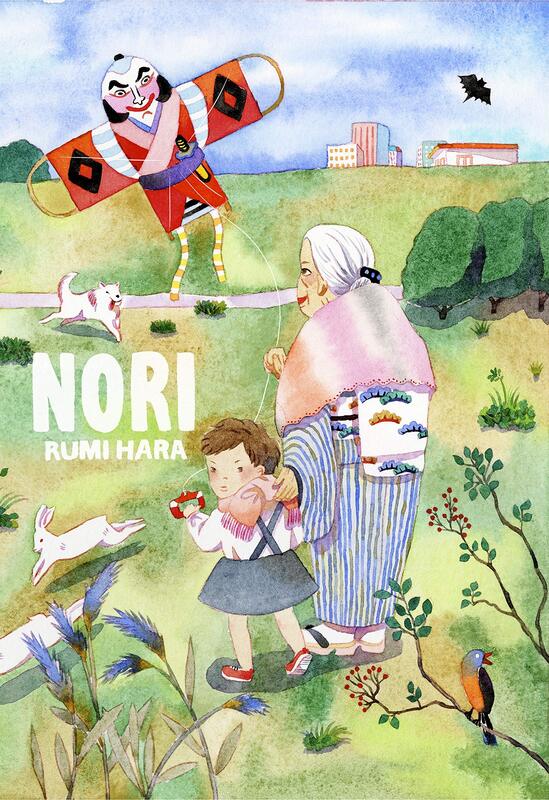

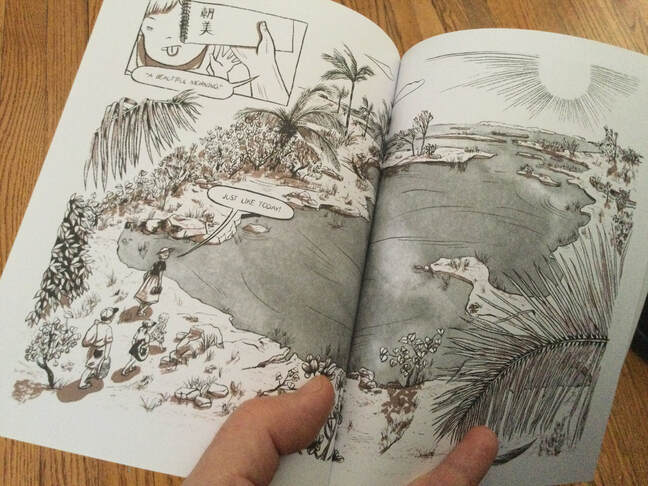

Nori. By Rumi Hara. Drawn & Quarterly, 2020. ISBN 978-1770463974, $US24.95. 228 pages. Collecting a series of minicomics begun in 2016. I regret not reading Nori sooner. It’s great: a poetic, beautifully observed portrait of one Japanese girl’s (and her grandmother’s) life, unforced, elliptical, and deeply personal. Sadly, this sort of evocative and searching book often gets dismissed by proponents of children’s books as too confusing or difficult (I know—I’ve been in quite a few conversations like that). Rumi Hara’s tale, seemingly semi-autobiographical, recalls a mid-1980s Japanese girlhood of a particular kind, in a scruffy, organic style that, for me, calls to mind Debbie Drechsler, early Lynda Barry, or Henrik Drescher. There's a similar fascination with texturing, in this case achieved through a versatile dry-brush technique that lends mood and specificity to each scene (Hara reportedly works on handmade paper, and her surfaces have a kind of nap, or nubbliness, a delicious roughness). Graceful use of a different spot color in every chapter imparts added flavor and also an overall sense of structure. I found Hara’s pages a bit disorienting at first—so rich are they—but man are they beautiful, and transporting. There are enchanting spreads here that just carry me away. Noriko, or Nori, an energetic girl of about four or five, is never disciplined out of her own free self, and remains, throughout, stubborn and even volatile, at times perhaps a bit of a pill, but really a delight. Her spirits are never sacrificed for some insufferable didactic point about maturing or becoming less of a challenge to grownups. Thank goodness. Nor does she just stand in for “childhood” as a vague state of freewheeling, unworldly innocence. She and her world are too particular for that—again, thank goodness. I grew to love this specific girl and her patient, but not over-idealized, granny, who in effect mothers Nori while the girl’s parents are busy working, working. This is a soulful book, empathetic and unpredictable, without obvious designs on the reader. Hara's storytelling takes an outside observer’s view most of the time, not giving us too-easy access into Nori’s (or anyone’s) thoughts, and sort of ambling from one thing to another, or so it seems, without obvious crises or problems to solve. But then bursts of dreamlike fantasy, brief and powerful, intervene, showing Nori's thoughts as she communes with her environment or works out her own fantastical logic. At those moments, Hara takes us in deep, but without ever showing her hand. We get glimpses of a magical but not overly sweet inner life; there's a touch of the uncanny as well (Hara says, "I like stories that have a little creepiness to them, like old folk stories that are simple but mysterious"). And as it turns out, the stories, which at first seem to have a shaggy-dog waywardness about them, are insinuating, carefully crafted, smartly rounded and complete, with levels and levels of implication and (if you care to reread and ponder) symbolism. Seeming threats turn into affirmations; the uncanny becomes lovable, yet never saccharine. I particularly enjoyed the long, ambitious story in which Nori and granny unexpectedly win a trip to Hawaii and have a wonderful, though complicated, visit there. Writing and art are both electrifyingly good here. I didn't get to read this, one of the best books of 2020, until a week into 2021. For shame! Most highly recommended. Drawn & Quarterly provided a review copy of this book.

0 Comments

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

Archives

June 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed