|

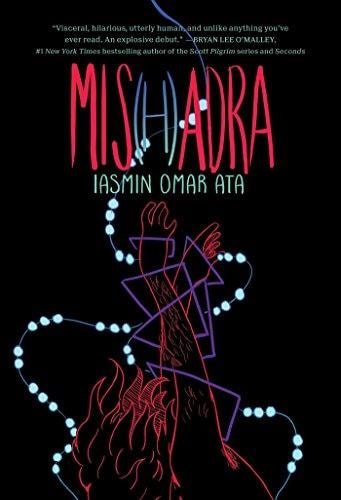

Mis(h)adra. By Iasmin Omar Ata. Gallery 13/Simon & Schuster, Oct. 2017. ISBN 978-1501162107. $25.00, 288 pages. Mis(h)adra, a sumptuous hardcover graphic novel, marks a startling print debut for cartoonist and game designer Iasmin Omar Ata, and has just been nominated for an Excellence in Graphic Literature Award (as, hmm, an Adult Book). Begun as a webcomic serial (2013-2015), its book form comes courtesy of a fairly new imprint, Gallery 13. Ata, who is Middle Eastern, Muslim, and epileptic, has described Mis(h)adra as "99.999% autobiographical" and "monthly therapy," but it's officially fiction: the story of Isaac Hammoudeh, a college student struggling to live with epilepsy, who seesaws back and forth from hope to hopelessness. The book's Arabic title, says Ata, brings together mish adra, meaning I cannot, and misadra, meaning seizure (perhaps it also echoes the word حضور, meaning presence?). Isaac desperately needs, yet cannot bring himself to accept, the help of family and friends, most particularly his new confidante Jo Esperanza (aha), who, to stay spoiler-free, I'll say faces profound challenges of her own. Mis(h)adra follows Isaac from despair and withdrawal to renewed hope, with Jo as his loving, sometimes scolding companion. The work is at once emotionally raw and aesthetically elaborate, bursting with style. While anchored in a familiar, manga-influenced look, one of simplified faces and flickering details, Mis(h)adra overflows with gusty aesthetic choices. Ata conveys the physical as well as psychological effects of epilepsy via fluorescent colors, exploded layouts, and the braiding of visual symbols: eyes, both literal and figurative, which are everywhere; strings of beads or of lights that ensnare Isaac; and floating daggers, which represent the threatening auras that warn him of oncoming seizures. The art is transporting, the seizures brutal and disorienting, yet beautiful. Tight grids give way to floating layouts. Bleeds are common, with lines sweeping off-page. Faux-benday dots, lending texture, are constant. Colors are bold and form a distinctive, non-mimetic system: pages come in pale yellow, sandstone brown, bright or dusky pink, and pure black; green and blue are used sparingly, often violently. The linework is not black but a dark purple, except on the pure-black pages, where lines of bright candy red assault the eye. Mis(h)adra renders epilepsy as a bodily and menacing experience. The story is not quite so surefooted. Only Isaac and Jo, and truthfully only Isaac, emerge as full people; almost everyone else is less a character than an indictment of normate society's insensitivity and cluelessness. The depiction of academic life is hard to credit. An explosive climax, shivering with energy and violence, gives way to an anticlimactic, fizzling resolution. Really, it seems that the book could go on and on with Isaac's struggle, but Ata simply ends because, well, a book has to stop. I felt as if the story were ending and then restarting over and over, uncertain of how to find its way. Mis(h)adra, then, is not a practiced piece of long-form writing. But it is testimony to the power of comics to create a distinct visual world, and to make a state of mind, or soul, visible on the page.

1 Comment

Ronna Klionsky

1/6/2019 03:30:44 pm

The review is apt. Thank you. I'M not a writer, let me just say that I agree with it's writer this beautiful presentation feels true. I don't imagine it is easier to draw an eplileptolic episode than it is to write about it.

Reply

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

Archives

June 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed