|

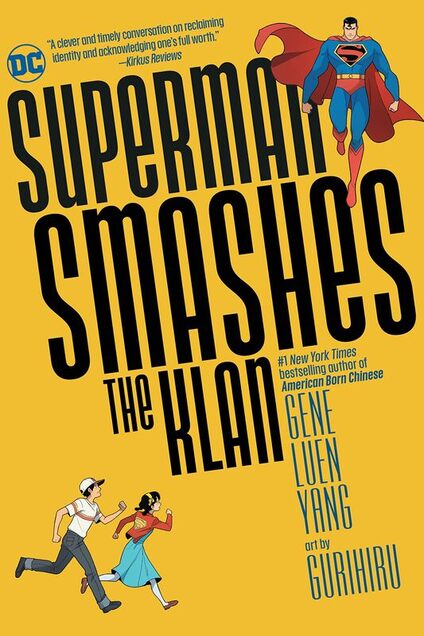

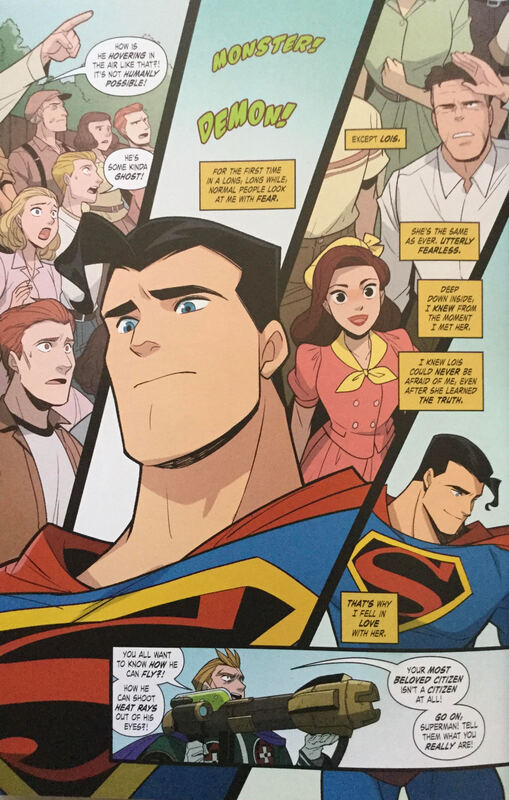

Superman Smashes the Klan. By Gene Luen Yang and Gurihiru. Lettering by Janice Chiang. DC Comics, ISBN 978-1779504210 (softcover), May 2020. US$16.99. 240 pages. (The first in an occasional series reviewing children’s and Young Adult graphic novels from DC.) One of the pleasures of reading Gene Luen Yang is watching him play — and take risks — with sources. American Born Chinese gives the Chinese literary classic Journey to the West an Americanized (and Christianized) spin, while riffing on sitcoms, Transformer-style mecha, and Yang’s own boyhood as an immigrant’s son. The recent Dragon Hoops (reviewed here in March) folds the history of basketball, reverently sourced, into its account of Yang’s last year as a high school teacher. Yang’s five-volume run on Avatar: The Last Airbender (2012-2017), his first collaboration with Japanese art team Gurihiru (Chifuyu Sasaki and Naoko Kawano), is a sequel to the beloved TV series (2005-2008). The Shadow Hero, Yang’s 2014 graphic novel with artist Sonny Liew, revives an obscure Golden Age superhero, Chu Hing’s Green Turtle (1944-1945), giving him a new origin and feel. Yang’s latest, Superman Smashes the Klan (now gathered into one volume, after a three-issue serial release last year), draws from an antiracist storyline in the Adventures of Superman radio serial in 1946, but adapts it freely. Superman Smashes the Klan interweaves several threads from Yang’s previous work. Once again, he plays with DC Comics and Superman lore; again, he collaborates with Gurihiru. Once more, as in The Shadow Hero, he treats the superhero-with-secret-identity as an overt assimilation fantasy, in a period American setting. It’s the best of his DC projects by a long shot: the most obviously personal, the most graphically whole, consistent, and readable. It’s also, I think not coincidentally, the one that comes closest to the children’s and YA graphic novel genre that Yang is best known for. This is one of the more interesting of the many 21st-century reinterpretations of Superman’s origin. It happens that my wife and I have been reading it at the same time as another reinterpretation, Tom De Haven’s prose novel It’s Superman! (2005). De Haven’s is a free retelling of Jerry Siegel and Joe Shuster’s original, late mid-1930s Superman, done up as nerdy, name-dropping historical fiction in the vein of Michael Chabon’s The Amazing Adventures of Kavalier & Clay (2000). It’s Superman! digs hard into that vein, stressing economic misery, political unrest, migration, segregation, and pervasive everyday racism in tune with its Depression-era setting. Also, it’s peppered with cameos by real-world people, neighborhoods, architecture — you name it, De Haven has researched it. Add in sexual knowingness, lurid violence, and odd character studies of crooks and victims, and you’ve got a very “adult” riff on the Siegel and Shuster model, something not too far from De Haven’s other comics-themed historical novels. Don’t get me wrong: It’s Superman! is a terrific book, one I’d like to teach when I get around to doing an all-Superman course. I think it would teach well alongside Superman Smashes the Klan, as both replay Superman’s origin in early 20th-century period (the mid-30s for De Haven; 1946 for this book) — and both stress Clark Kent’s moral education, his growing awareness of social injustice. Yet the two books are quite different. De Haven’s Clark never finds out where he came from; though he suspects that he is not from Earth, he never learns about planet Krypton. The book only hints at Clark’s origins. De Haven works hard to suggest how this lonely, alienated young man might turn to reporting, and to his unrequited love for Lois Lane, as a way of becoming “just like everybody else.” Yang and Gurihiru’s Clark, on the other hand, learns more about his extraterrestrial origins — there’s more SF in his story. He too, though, longs to be like everyone else, to assimilate — so much so that he hides his light under a bushel, downplaying or even failing to recognize some of his powers. He befriends young Roberta and Tommy Lee, children of a Chinese immigrant family that has just moved to Metropolis, and combats a militant, White supremacist Klan group that terrorizes them. At the same time, he must confront his fears of revealing his own alienness, and frightful visions of himself and his birth parents as green-skinned monsters. This Clark starts out not knowing about Krypton, but gradually learns of it (through a familiar plot device: a bit of leftover Kryptonian tech). In the course of fighting the Klan, Clark discovers the full extent of his powers, hidden from him by his own desires to assimilate: a clever way to explain how the running and jumping Superman of early Siegel and Shuster became the flying Superman with X-ray vision that we know now. But much of the story belongs to young Roberta (Lan-Shin) Lee, whose worries about fitting in mirror Clark’s, and whose empathy with him proves key to unlocking his potential. Yang and Gurihiru give us brief flashbacks to Clark’s origin, while focusing on his anxious way of passing among humans in the present — an anxiety Roberta knows all too well. The book's nonlinear retelling deftly frames the old origin story as a fable of assimilation (à la The Shadow Hero). Roberta and Clark, both immigrants uncomfortably aware of their alienness, together foil the Klan and stand up for a vision of Metropolis — implicitly of America — in which everyone is “bound together,” sharing the same future, “the same tomorrow.” In this way, Superman Smashes the Klan makes its antiracist parable integral to Superman’s own process of becoming. Superman Smashes the Klan is not subtle; after all, it’s a value-laden fantasy of nation, like so many American superhero comics — and it obviously courts a young audience (Young Adults, says the back cover, but I’d say middle-grade). The book wears its values on its sleeve. Also, the period setting seems idealized: for example, Inspector Henderson of the Metropolis PD is here portrayed as African American, which tends to suggest a very progressive Metropolis for 1946, one in which the Klansmen’s anti-Black racism makes them outliers. This may be too easy. Though the story acknowledges that racism takes many forms, the masked Klansmen provide an obvious, simplistic focus (I’d expect a YA novel about racism to be more ambiguous and challenging on this score). On the other hand, the book allows some of its racist characters to grow: young Chuck, nephew of the Klan’s leader, learns to reject his uncle’s ways at the boffo climax — at which a bunch of kids help Superman save the day, own his identity, and face down xenophobia. Superman Smashes the Klan, then, dares to hope — as children’s texts so often do — that the openness and innocence of the young can redeem a society riven by bigotry and corruption. This utopian vision is familiar to anyone who studies children's literature; it's obvious. Yet, obvious or not, this is just the kind of Superman story I prefer to read, one in which Supes clearly stands for a decent, humane, inclusive ideal. It’s on the nose, sure, but that doesn’t bother me much. It could make a terrific animated film, in post-Spider-Verse mode (we can only hope). That said, Superman Smashes the Klan is not as effective, I think, as Yang and Liew’s Shadow Hero, which more daringly uses superhero tropes to create a layered, ambivalent assimilation story. This is a Superman comic, after all, hence constrained; the nervy, potentially offensive gambits in The Shadow Hero are not to be expected. Yet Yang has taken some interesting risks in reworking Superman’s origin; it’s good to see the truism that Superman is an immigrant being put to real use. It’s likewise good to see Superman sprung free — liberated — from the suffocating weight of “DC Universe” continuity. I'm a little sad that this has to happen in a distanced period setting, rather than a contemporary one. (I'd love to see this book spawn a series of timely, obviously relevant Superman GNs set in the present day, for the same audience.) Stylistically, I’ll say that I find the book a bit too clean and antiseptic to conjure the desired sense of period; Gurihiru’s neat, smart artwork strikes me as too textureless and bland to evoke a mid-1940s Metropolis. I’d have liked to see a grittier city setting, with more grimy particulars, so that Superman’s bright, heroic doings would stand out by contrast. On the other hand, Gurihiru’s pages are dynamic, inventive, and ever-readable. The book combines the snazziness and roughhousing energy of most superhero comics with clear-line legibility. It’s fetching and fun to look at, and Yang and Gurihiru are clearly sympatico (their Avatar collaboration obviously prepared them for this). If only most DC comics were this free and confident of their aims. The recent news that Marvel is teaming up with Scholastic — that is, licensing Scholastic to produce a series of original graphic novels for young readers starring Marvel heroes, to be published under the Graphix line — gives me hope that we may see a flood of comics with similar aims. That announcement came as a surprise, but perhaps it shouldn't have: after all, young readers' graphic novels are the thriving sector in US comics publishing today. Maybe, just maybe, US-style superhero comics, not just movies, TV shows, and goods based on such comics, can once again become popular, widely available children's entertainment. Having lived through (and, for a time, invested emotionally in) the revisionist adultification of superheroes in the 1980s to 90s, I find this prospect oddly exhilarating. I wonder what Yang thinks — and if he is keen to do more books of this type. Man, what I wouldn’t give to teach a sequence like so: Siegel and Shuster’s first two years of Superman (1938-1940), De Haven’s retake, The Shadow Hero, and Superman Smashes the Klan. I bet that would kick off some great conversations. PS. Gene Luen Yang has been on the board of the Comic Book Legal Defense Fund since 2018. In light of the infuriating recent news out of that troubled organization, his frank and reflective remarks on Twitter have been illuminating. Yang — wisely, I think — values the Fund's mission over the current organization, while also pointing out the good work done by current CBLDF staffers. It's quite a tightrope walk — and recommended reading for those who've been following the news of the CBLDF, and the comic book field's larger sexual harassment and abuse crisis, on this blog. PPS. Gene Yang is slated to take part in three virtual panels at this week's Comic-Con@Home: The Power of Teamwork in Kids Comics (today, Wednesday, July 22); Comics during Clampdown: Creativity in the Time of COVID (Thursday, July 23); and Water, Earth, Fire, Air: Continuing the Avatar Legacy (Friday, July 24). These events, like most panels making up Comic-Con@Home, will presumably be prerecorded, hence without live audience Q&A, which is a shame. But, still, there should be some interesting back-and-forth among the panelists, and Yang is a great ambassador and thinker on the fly. See comic-con.org or Comic-Con's YouTube channel for further info.

0 Comments

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

Archives

June 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed