|

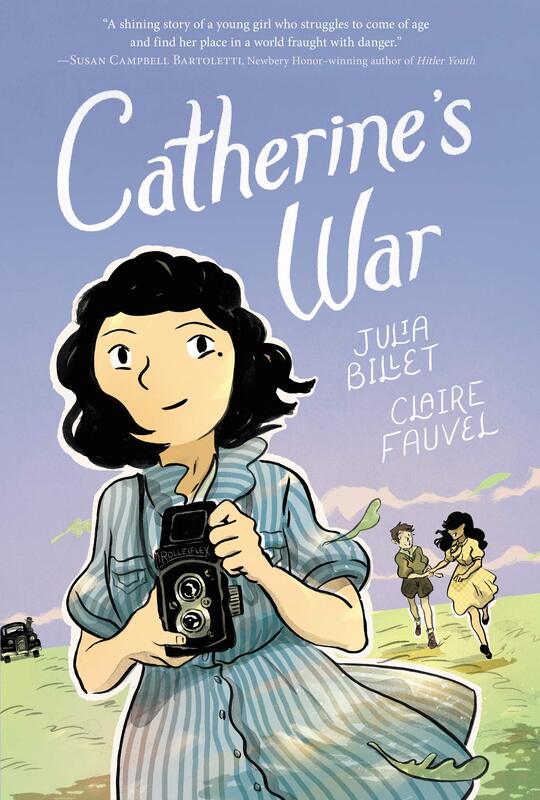

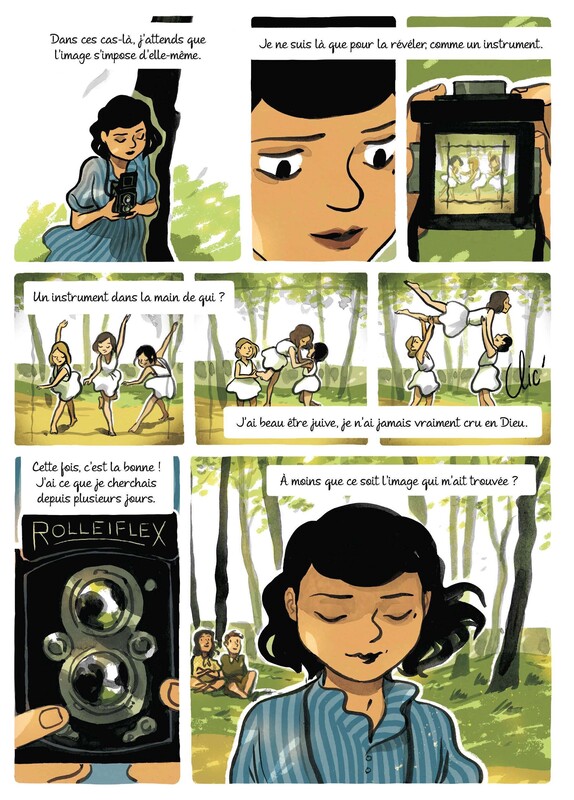

Catherine’s War. By Julia Billet and Claire Fauvel. Translated from the French by Ivanka Hahnenberger. HarperAlley, 2020. ISBN 978-0062915597, $US12.99. 176 pages. Catherine’s War is a finely shaded, beautifully cartooned, and engrossing book that ends much too abruptly. A historical novel stenciled from real events, it has been translated from the Angoulême Youth Prize-winning BD album La guerre de Catherine (Rue de Sèvres, 2017), which adapts Julia Billet’s prose novel of the same name (2012). Billet’s novel itself freely adapts, or at least draws inspiration from, the wartime story of Billet’s mother, Tamo Cohen, one of thousands of hidden children uprooted by the Holocaust: Jewish children sheltered from the Nazis, often in Catholic convents or among Gentile families. In real life, Tamo Cohen did attend the Sèvres Children’s Home (in fact a progressive, student-centered school), as does the protagonist of this novel, Rachel Cohen, and she did flee the Nazis, and she was renamed to pass as a Gentile, just as Rachel here is renamed “Catherine Colin.” But, as Billet admits in her notes, the story of Catherine’s War “remains a story”—a historical fiction interwoven with truths. Billet imagines Rachel/Catherine as a young photographer whose images of WWII are successfully exhibited in a Parisian art gallery soon after the war (an exhibition that replays many experiences depicted earlier in the book). Further, Rachel’s narration, implicitly, comes from her journal—so, she is an artist in words as well as pictures. In that sense, Catherine’s War becomes a Künstlerroman as well as a wartime tale of life on the run. Thematically, it reminds me of books like Whitney Otto’s ensemble novel Eight Girls Taking Pictures (2012), a fictionalized biography of eight women photographers, and comics like Isabel Quintero and Zeke Peña’s Photographic (2017), a YA biography of famed Mexican photographer Graciela Iturbide. Reframing Tamo Cohen’s story within the history of photography, Billet casts her mother, or rather Rachel, as a visual witness to the terrors of war. Armed with a Rolleiflex (like Robert Capa – or Annemarie Schwarzenbach?), the fugitive Rachel/Catherine becomes a chronicler as well as autonomous artist, even as she rushes from one shelter to the next to evade the Nazis. For all that, Catherine’s War is not explicitly violent. Though fear is ever-present, intimations of war and Holocaust are discreet; we never see the dreaded roundups or camps, or combat (though overheard dialogue among Resistance fighters does imply sabotage). The point of view is limited to what a child in hiding, pretending to live out her normal life, might have witnessed. Trauma is suggested by the extent to which Rachel and other young people help each other cope with it. The various children depicted (the story begins at the Sèvres home, and Rachel most often travels with other kids) are wounded by the shocks and partings they have to endure, yet they are resourceful, brave, and unselfish—not to the point of absurd angelic idealization, thank goodness, but in a tense, believable way. (Billet’s trust in young people mirrors the radical teaching philosophy of the Sèvres school.) Multiple scenes depict the challenge of trying to keep cover stories straight, the distrust stoked by constant surveillance, and the dread of giving the game away. Yet the novel is so discreet that it takes Billet’s endnotes to flesh out the terrible context of WWII. Those notes clearly anticipate a young audience, and I note that the book is blurbed by a notable writer of children’s nonfiction, Susan Campbell Bartoletti, whose work (Hitler Youth, Kids on Strike!, etc.) often extols young people’s activism and recounts harrowing historical facts with candor but also due sensitivity. Decorous would describe this book’s approach: from the story’s quiet hinting, to Claire Fauvel’s rippling brush-inking, gentle watercolors, and borderless panels, to the prim digital lettering (by David DeWitt). A genteel aesthetic overlays everything, conferring delicacy despite the nightmarish world evoked. What makes all this work is Fauvel’s patience, empathy, and attention to detail: from the opening pages, she tracks Rachel and the other characters with exquisite care, and their feelings, both spoken and unspoken, register honestly. Fauvel’s visual storytelling, if understated, is fluid and confident, moving characters about gracefully and capturing unwritten nuances in most every scene. She really cares about these characters. In short, Catherine’s War is smartly laid out, superbly drawn, and piercing. (For insight into Fauvel's process, and the book's production, see Billet's VanCAF presentation from last spring: a slideshow and talk captured on video, subtitled in English.) Not everything in the book works. There are moments where the book seems determined to spell out, rather than suggest, its messages—passages that seemed forced. In particular, a postwar scene depicting the ritual shaming (head-shaving) of French women accused of Nazi collaboration seems underdone; it doesn’t explain what’s at stake, and Rachel’s rejection of the shaming mob doesn’t register (though Billet’s endnotes work hard to underscore the didactic point). Also, as the book accelerates toward its end, things happen rather too fast. Both a crucial relationship and the postwar arc of Rachel’s life are sketched in abruptly over the last couple of pages. (It turns out that there’s a sequel, published in French in 2020, so perhaps the ending was meant to be a springboard?) When I turned the final page, I felt as if I was still in midair. That said, the gnawing dissatisfaction I felt got me to reread the book, which sharpened my appreciation of Fauvel’s subtle artistry. As I say every so often, I’d be glad to read more.

0 Comments

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

Archives

June 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed