|

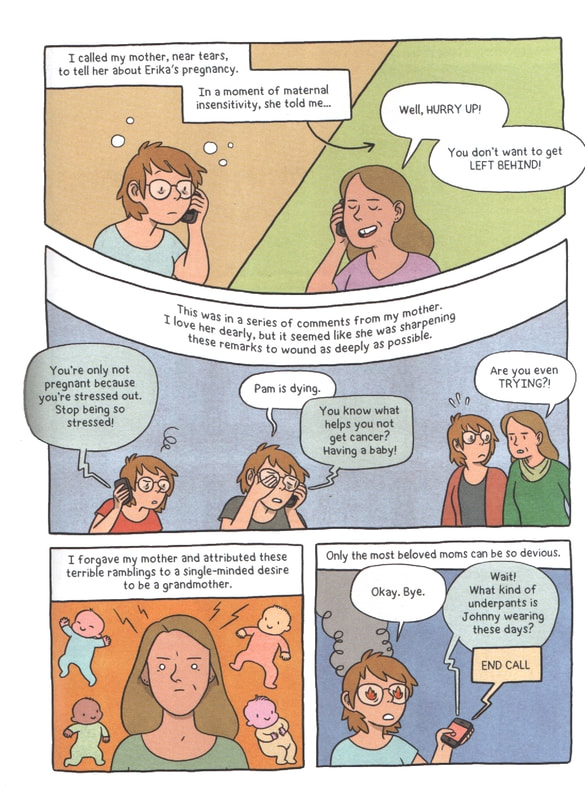

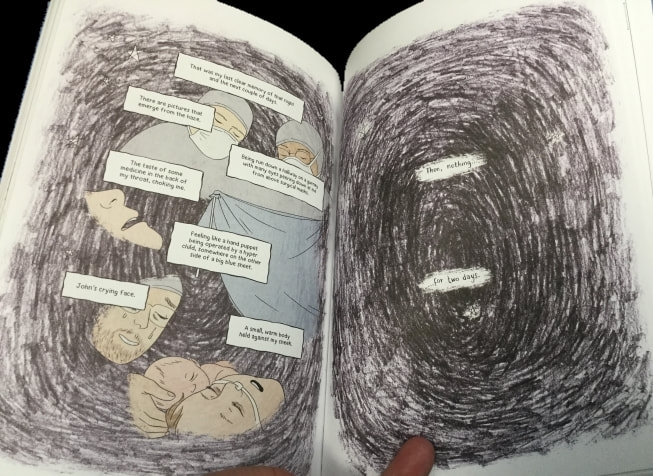

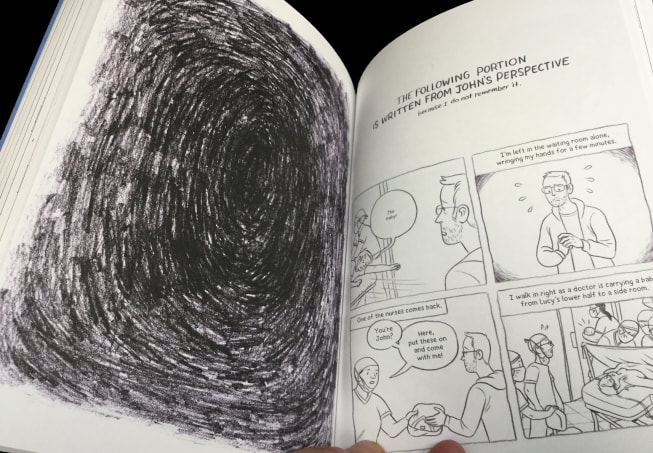

Kid Gloves: Nine Months of Careful Chaos. By Lucy Knisley. First Second. ISBN 978-1626728080 (softcover), $19.99. 256 pages. Kid Gloves tells of author Lucy Knisley’s pregnancies and miscarriages, and finally the birth of her and her husband’s child. Blending memoir, childbirth education, and self-help, the book also offers, at times, sharp criticism of both sexist birthing institutions and natural childbirth truisms. Between chapters of personal narrative, Knisley inserts brief interchapters devoted to “pregnancy research”—actually, a mix of contextualizing details and Knisley’s pointed editorializing: often humorous, sometimes exasperated. These interchapters are didactic but droll, and not impersonal; they resonate with Knisley’s own story. The larger personal narrative takes us through Knisley’s miscarriages and resulting depression, then on through the conception, bearing, and delivery of her child—itself a traumatic, life-threatening event (due to eclampsia and seizure). A lot of scary stuff is replayed in this story, but also a great deal of joy and good humor. Knisley comes across as a friendly but not uncritical guide to the vagaries of pregnancy, opinionated, blunt, and confidential. She relays her story from a safe retrospective distance: her introduction shows Lucy and the baby, weeks after delivery, doing okay, and the narrative captions reassuringly carry us along. That is, the story is recounted in hindsight, rather than rawly dramatized. All this is delivered (sorry!) via Knisley’s reliably excellent, toothsome cartooning, dynamic yet readable layouts, and beautiful colors—signs of her offhand mastery of the craft. Wow, can she make comics. I admit I approached Kid Gloves a tad nervously, unsure of whether Knisley’s writing would be equal to her subject. My first experience of her work, her memoir Relish (2013), had frustrated me with what I took to be its unexamined entitlement, skirting of emotional complexity, and preference for glib affirmation over fierce self-examination. Knisley does not do raw confessionalism or self-damning underground memoir. While her work does take on hard things, she tends to adopt a position of earned confidence and matter-of-factness (again, self-help is a useful point of reference). Her rhetorical construction of self is not the fractured self of Green or Kominsky-Crumb, nor the compulsively self-questioning, reflexive self of Spiegelman or Bechdel (though she does indulge here in comically grotesque caricatures of her changing body and its trials). Knisley the narrator seems secure even when Kid Gloves depicts the depths of depression or the harrowing trials of illness and emergency. It is a reassuring sort of memoir that offers a sane perspective-taking rather than an unsettled, open-ended questioning (in this, it reminds me of what Ellen Forney has done in her memoirs of bipolarity). Indeed, at times Kid Gloves skates over complex things much as Relish did. For example, in a sequence that my wife Michele called to my attention, Knisley recalls the aftereffects of one of her miscarriages, and what she characterizes as her mother’s insensitive response: You might think that this characterization would lead to a considered treatment of her mother throughout the remainder of the book, one that would balance daughterly love and forgiveness against frustration and critique. But Knisley accepts this tension between mother and daughter as an unresolvable, and moves on, not revisiting these hard feelings but tucking them away. (You won’t find here, for example, the extended, ambivalent treatment of parent-child relationships that you’ll see in Thi Bui’s The Best We Could Do.) I worried that this key moment, which comes early in the text, would cancel Knisley’s piercing depictions of depression, that she would paper over complexities in the quest for a feel-good equanimity such as we so often see in popular memoir and self-help books. Knisley, however, proved me wrong. Her narrative goes on to address challenging issues, including her and her husband’s anxieties, her triggers and preoccupations, the wrenching bodily demands of pregnancy, and her tense relationship with childbirthing dogma. The actual birth of her son, accomplished by cesarean and blurred out by medication, brings an explosive change to Knisley’s pages, suggesting lingering trauma and loss. Further, when her own life hangs in the balance, Knisley switches focalization to her husband, with drastic changes in her technique. There are moments when her always decorous, conspicuously well-designed pages become unsettled and the delivery of her story becomes most piercing. The book’s climax moved me beyond my expectations. Michele read Kid Gloves before I did, and told me frankly that the book raised up some difficult memories for her. This was perhaps another reason why I approached the book with a bit of dread. It’s true that reading it brought up some of my own memories of how Michele and I wrestled with medicalized childbirth and its outcomes. Frankly, I was surprised by how much Knisley criticizes natural childbirth rhetoric and embraces what she calls “hospital-based interventions” (even as she recounts what were arguably cases of medical malpractice). Kid Gloves, it's fair to say, takes a jaded view of the power struggles between obstetrics and traditional midwifery. These notes brought up memories of our own childbirthing experience; they also got me to question Knisley's wisdom. At times, the old feelings of impatience regarding her writing came back to me. There was a whiff of unexamined entitlement about Knisley's weighing of women’s “choices” in childbirth (“as long as everyone’s healthy”), and behind her settled self-presentation I sense a certain hardheadedness. But, still, Kid Gloves is a forthcoming and bracing story, one that will surely prove inspiring to many readers going through the childbirthing experience or seeking to put it into perspective afterward. By book’s end, I felt grateful for the ride. In sum, Kid Gloves uses the all-at-onceness and richness of the comics page to tell a story that is at once personal, instructive, and political. I don’t quite love it the way I love comics that tell of childbearing from a rawer, less protected place (check out Lauren Weinstein’s superb Mother’s Walk), and I note that Knisley continues to walk the knife’s edge between personal exploration and tidy, marketable endings. But Kid Gloves marks a step forward for her as a writer, and I recommend it.

0 Comments

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

Archives

June 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed