|

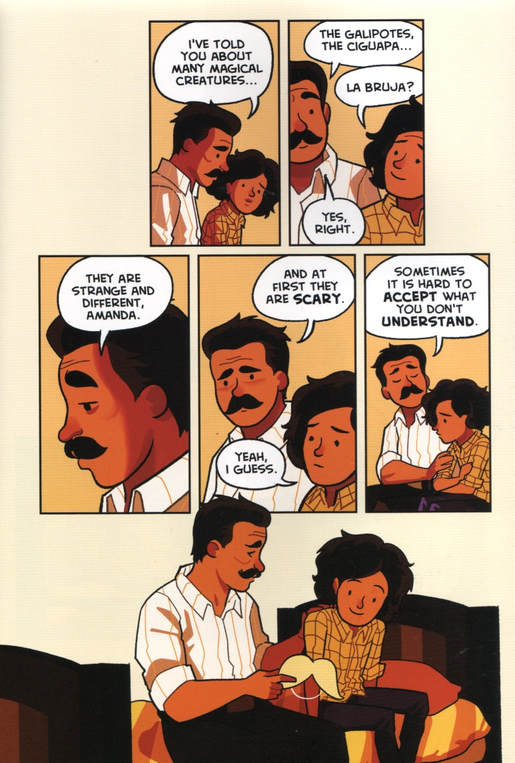

The Cardboard Kingdom. By Chad Sell, with Vid Alliger, Manuel Betancourt, Michael Cole, David Demeo, Jay Fuller, Cloud Jacobs, Kris Moore, Molly Muldoon, Barbara Perez Marquez, and Katie Schenkel. Alfred A. Knopf/Random House Children’s Books, June 2018. ISBN 978-1524719371. Hardcover, 288 pages, $20.99. The Cardboard Kingdom celebrates community and in fact is the work of a community: a team made up of cartoonist and creator Chad Sell and ten co-writers, referred to by the publisher as “new and diverse authors” (one of whom, Kris Moore, sadly seems to have passed away). An impressive collaborative feat, it depicts an idealized neighborhood of kids who also collaborate, turning their everyday lives into, basically, a nonstop live-action roleplaying game. A paean to shared creative play—essentially, the book is about kids as cosplayers, crafters, and friends—it must also have been a playful, if complicated, project. Happily, everything clicks. The book works as an anthology of short stories and vignettes, from about five to thirty-plus pages in length, but more powerfully as a novel, which, though episodic, designedly builds to a big and satisfying finish. Sell enlisted each author to write a story or two, and then apparently brought them together to cook up the boffo finale. Reading it straight through, it’s almost seamless; the novel builds its neighborhood carefully, gradually introducing new characters into its busy communal scenes. Though the publisher says The Cardboard Kingdom is about “sixteen kids,” I counted nineteen distinct, recurring child characters in the novel, some identified only by their roleplaying names, some known by more than one name. There’s a lot of juggling going on, but never to the point of distraction. The publisher also says that the book depicts “adolescent identity-searching and emotional growth”—yet it certainly isn’t YA fiction. My sense is that The Cardboard Kingdom is emphatically a middle-grade novel, aiming for upper elementary to perhaps middle school age. While its large cast, complex rigging, and lively and dynamic pages say “middle-grade” to me (not younger), its eager, almost ingratiating cartoon style reminds me of Pixar—say, Inside Out, with its mix of emotional gravity and toylike cuteness. Certainly the book depicts identity-searching and emotional growth; however, its bright cartooning, winsome children, and almost Peanuts-like sense of suburbia (not wholly idyllic like Schulz’s but still reassuringly safe) seem pre-adolescent in tone. Its let’s-pretend and DIY ethos brings back some early memories of my own. I mention this not because I’m concerned about age levels (KinderComics doesn’t usually focus on leveling) but because I’m interested in The Cardboard Kingdom’s treatment of identity, which I consider bold for a middle-grade novel. If graphically the book suggests years of reading Peanuts and Tintin, its imagined neighborhood has a utopian queer- and trans-positive vibe that would make it a good companion to, say, Alex Gino’s groundbreaking George (also a middle-grade fiction). Among the book’s young role-players are several who defy or ignore gender norms. In fact the first story, “The Sorceress,” written with Jay Fuller, introduces a cross-dressing pair: the titular Sorceress, soon shown to be (ostensibly) a boy but only much later identified as “Jack,” and his neighbor, a seeming girl who refuses the princess role and becomes The Knight (I don’t think she ever gets another name). Reportedly, this story was the kernel or inspiration for the whole book. There’s more: one character, Sophie, defies expectations of sweet girlishness and becomes a rampaging, Hulk-like bruiser she calls The Big Banshee; another, Amanda, a self-styled Mad Scientist, worries her father by wearing a mustache. Meanwhile, the relationship between Miguel the Rogue and Nate the Prince hints at a young gay crush. The Cardboard Kingdom, in fact, resists conventional gender and sexual roles throughout. For all that, it’s a story about kids who like to imagine combat: big, frenzied dust-ups between heroes and villains. Reading it, I was more than once reminded of an Avengers movie. If the drawing style and solid, bright colors follow a clear-line aesthetic, recalling the moral and ideological sureties of so many children’s comics, then Jack Kirby is surely a reference point too, from the Big Banshee’s unabashed monstrousness (more cheerful than tragic here) to the outrageous costuming, replete with spiky cardboard headgear that would do Cate Blanchett proud. The book taps the same vein of explosive fantasy that superhero comics do, but with more charm than most. The neighborhood kids of The Cardboard Kingdom, though they never really hurt one another, like to run around and fight; Sell and company are unafraid of children’s capacity to play at physical conflict and violence. Further, many of the kids like to be “bad guys” as well as “good,” and the book gleefully mines that tendency for humor. There’s a disarming mixture of sweetness and brutal imaginings in the book, though it all comes out seeming like harmless fun. Sell and his collaborators have a feel for the reckless, revved-up fantasy lives of young kids hanging out together--I appreciate that. And no adult ever dictates the terms of, or reins in, what the kids are fantasizing about. The book presents an entirely child-driven and child-centered world of cooperative, if pugnacious, play. In short, it’s feisty as well as sweet. Behind its bright, cheery surface, then, The Cardboard Kingdom is structurally tricky and thematically gutsy. On the critical side, I would say that some of its component stories resolve too quickly; the book runs the risk of being too neat, because its nested structure and sheer number of characters demand fast pacing, even when dealing with hard matters of identity and parent-child tension. Problems are invoked and solved with speed. In that sense, it’s, again, utopian. Also, the book makes some obvious, even heavy-handed, didactic moves, though in the direction of adult chaperones rather than child readers. Its sharpest lessons will likely be ones of forbearance and acceptance aimed at concerned parents whose children are behaving, well, unexpectedly. The best examples of parenting in The Cardboard Kingdom involve suspending or tempering judgment, i.e. being brave about children’s imaginative self-fashioning (would that all anxious parents course-corrected as readily as those in the book). But, most of all, it’s the book’s wise embrace of childhood play that makes The Cardboard Kingdom a brave and interesting graphic novel, one I highly recommend. Random House provided a review copy of this book.

0 Comments

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

Archives

June 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed