|

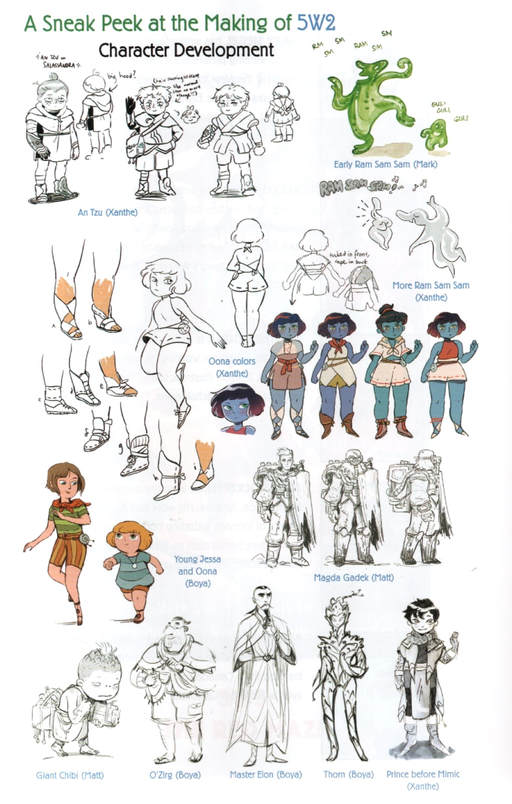

5 Worlds: The Cobalt Prince. By Mark Siegel, Alexis Siegel, Xanthe Bouma, Matt Rockefeller, and Boya Sun. Random House, May 2018. Paperback: ISBN 978-1101935910, $12.99. Hardcover: ISBN 978-1101935897, $20.99. 256 pages. Epic fantasy is a balancing act. On the one hand, its make-believe settings tend to be rule-governed and to strive after internal consistency, as if some kind of voluntary constraint were needed to hem in and discipline the pure exercise of fancy. We have to know that the characters, however magical, won't be able to do just anything they please, and that the worlds won't simply change in mid-story to suit the storyteller's whims (anyone who has ever played Dungeons & Dragons with a very whimsical DM knows how annoying that can be). Tolkien's Middle Earth has set a standard: that high fantasy worlds are to be approached with something like the self-discipline of historical fiction, even if that kind of discipline belies the very term fantasy. On the other hand, epic fantasy series, as they sprawl, often reveal new things about their worlds that shift the terms of our understanding. They elaborate, giving us more and more backstory that impinges on, or changes the stakes of, the story we're reading. Multi-volume fantasies, as they ravel out, tend to disclose (or discover) more about origins or antecedent conditions, uncovering deep foundations that may generate new problems. Even Tolkien, who crafted a history of Middle Earth before he publicly shared that world, famously said that The Lord of the Rings "grew in the telling," which I take it means that the book (ultimately trilogy) ended up drawing in more and more of the mythic backstory as he had privately envisioned it. Of course, there are also epic fantasy series written without the same strict dedication to consistency: say, Zelazny's Amber, with its odd, shifting rules. Such shifting or feinting may betray Tolkien's disciplined mode of high fantasy, but I confess I enjoy twisting, ramifying plots that reveal more of a world to me, even when the twists undermine what I thought I knew about the world at first. Consider the way Rowling's Harry Potter turns out to be a multigenerational saga set in a world more layered, and corrupt, than the first book shows, or the way Le Guin’s Earthsea, in its later books, dismantles its own patriarchal foundations, or the way Jeff Smith's Bone, in the seventh-inning stretch, gets more tangled and complex. In a satisfying fantasy epic, we will come to believe that all the complications were foreordained and fit perfectly. Besides self-consistency, then, I do enjoy the continual deepening of fantasy worlds. I bet a lot of readers do. As we travel the worlds, we learn, even as the heroes do, how complex the worlds truly are. That, I think, is the effect that 5 Worlds is going for. 5 Worlds, a collaborative graphic novel series that launched last year, does not quite persuade me that everything has been worked out, or that everything fits. Its cluster of worlds is complicated, even baroque, yet its plot is a breathless, rocket-propelled blur. I reviewed the first volume, The Sand Warrior, here recently, and complained that the tale suffered from tangled plotlines, a frantic pace, and too much downloading of mythic backstory. The second volume, The Cobalt Prince, is due out this week, and guess what? It has all those same qualities. The Cobalt Prince does not "solve" the "problems" of The Sand Warrior, and there are moments where its storytelling gets muddled. However, the book is splendidly imaginative, enough so to make its problems into virtues—which is to say that I'm glad to be revisiting 5 Worlds and exploring its universe. There's a lot going on here, plot-wise, and the book is a delirious exercise in graphic world-building. Thankfully, it remembers to round out and humanize its characters as it goes, and so attains a poignancy that the first volume lacked. If The Sand Warrior seemed promising, The Cobalt Prince is grand. By way of recap (here I'll crib from my first review), 5 Worlds is a science fantasy co-scripted and designed by cartoonist Mark Siegel and his brother Alexis Siegel and then further designed and drawn by three other cartoonists, Xanthe Bouma, Matt Rockefeller, and Boya Sun. Its plot revolves around an ecological catastrophe that threatens five rival yet interconnected planets. These are Mon Domani, the so-called Mother World, and her four satellites, each with a distinctly different culture. All five worlds are drying out and dying of heat death. Per an ancient prophecy, this disaster can be averted by relighting the long-dormant "Beacons” on each world, but not everyone believes the prophecy. Rivalry among the worlds gets in the way of cooperative problem-solving, and a shadowy adversary known as the Mimic (a sort of Dark Lord) exploits this rivalry in order to sow invasion and war. Our heroine Oona, an unfledged “sand dancer” of Mon Domani, seeks to relight the Beacons and stop the Mimic, with the help of a resourceful urchin named An Tzu and a sleek android called Jax. The first book centered on Mon Domani, but The Cobalt Prince moves on to other worlds: Toki, home of the despised, racially Othered "blue-skins," and Salassandra, home to diverse religious orders. Though Toki is the main theater of action, the plot caroms from place to place. When first I saw The Cobalt Prince, I noted Jax's absence from the cover—and sure enough Jax gets sidelined along the way, as if his story were one too many for this book. A plethora of new characters more than fills his space, and The Cobalt Prince becomes a roll call of unfamiliar names assigned to familiar archetypal roles: Master Elon, a mentor and outlaw; Ram Sam Sam, a cute ectoplasmic critter; O'Zirg, a shopkeeper; Anselka, a healer; and Magda, another mentor, this one a Master Yupa or Obi-Wan type who possesses essential knowledge. These figures become helpers or donors to our heroes (in folklorist Vladimir Propp's sense). They also bring new info, as, in good fantasy fashion, The Cobalt Prince dives into fresh elaborations and disclosures. So, even as this second book explains and solidifies things that happened in the first, it also changes the terms of the first, complicating what was already tricky. Along the way, it changes how we think of Oona (and how she thinks of herself) and makes Oona's sister Jessa, a morally ambiguous figure in the first book, into the linchpin of the plot. The sisterhood of Jessa and Oona turns out to be this book's core. Narratively, The Cobalt Prince, like The Sand Warrior before it, is a mixed bag. On the plus side, the book's elaborations are emotional as well as clever, giving it more gravity than its predecessor. Also, I like the way its plot presses on the issue of racism as both personal animus and systemic oppression. In this story, distrust and division are keyed to skin color and culture, and at times racist hatred or fear threatens to misdirect our heroes. The challenges of transcultural understanding lend the frenetic, pinballing story greater depth. However, some of that subtlety gets fumbled along the way to a grand finale: a gathering of forces that, in its rigging, reminds me of The Hobbit's Battle of Five Armies, though sadly it comes across less clearly. The book, finally, stacks up too many plot points at once. A frenzied fight between giant, godlike avatars is particularly confusing, as those beings are possessed first by one side, then by the other, blurring the action's meaning. I had to reread some pages two or three times to understand what was happening, to whom, and why. When I finally did "get" it, it was rather glorious, but on first reading I was a bit lost. An anticlimactic but necessary "epilogue" does the work of sorting things out and springboarding readers onward to the next volume. I know I'll be there, waiting to see what complications the plot delivers next. Like its predecessor, The Cobalt Prince is beautifully designed, drawn, and colored, a rapturous outpouring of images. The five-person 5 Worlds team continues to be a collaborative miracle. The book wears its visual influences on its sleeve: a temple scene on Salassandra recalls Moebius; a chase scene involving starships and an "escape pod" cannot help but evoke Star Wars. Miyazaki looms large: treks through a post-apocalyptic "wasteland" echo the opening of Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind, while the final battle invokes Princess Mononoke's giant Forest Spirit but also its sense of ecological renewal, as the dead wasteland blooms green again. 5 Worlds, then, is frankly an exercise in allusion and synthesis. The reason I not only tolerate but savor these familiar elements is that, against all odds, the 5 Worlds team makes everything seem of a piece visually. 5 Worlds continues to be a grand experiment that seems ever in danger of flying off the rails. I hope the books to come will slow down, find their feet narratively, and deliver their action more clearly. I look forward to seeing how the team's world-building and piling-up of ideas comes together as an epic whole. Will everything fit perfectly? Of course I can't say yet, but the journey is head-spinning. Random House provided a review copy of this book.

0 Comments

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

Archives

June 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed