|

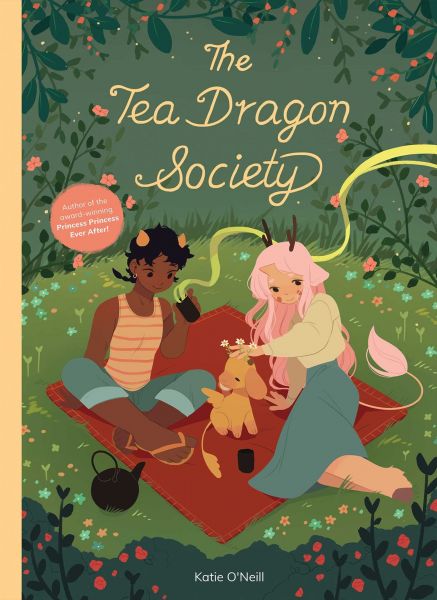

The Tea Dragon Society, by Katie O’Neill. Oni Press, 2017. ISBN 978-1620104415. 72 pages, hardcover, $17.99. Designed by Hilary Thompson. A gentle, winsome fantasy set in an unspecified secondary world with hints of backstory, The Tea Dragon Society is a lush, verdant, lovely thing: an exquisitely rendered, Miyazaki-esque idyll full of greenness and life. Testimony to a very specific set of passions, the book practically elevates cuteness—in the form of miniature, catlike dragons who have to be coddled and protected—to a moral good. In this world, traumas and losses have happened in the past, to be sketched in via poetic flashbacks, while the present action has a quiet, almost palliative quality (absent Miyazaki’s occasional hardnosed gift for terror and trial). The artwork conjures forms and volumes through blocks of color rather than heavy linework, and makes me swoon from its sheer gorgeousness. Aesthetically, then, the book as Object fairly mesmerizes me, though I confess that the ingratiating sweetness of the conceit, the world and its dragons, wears on me a little. Call me a grouch. Ironically, this handsome, bookish book began as a webcomic. I say ironically because The Tea Dragon Society is a heartfelt paean to traditional crafts—blacksmithing, dragon-tending—and the people who keep those crafts alive, passing on skills and techniques but also, most importantly, memories, both personal and cultural. The protagonist, Greta, a young smith in training, rescues a lost tea dragon and finds herself entering a new world of dragon-keeping, one of utmost delicacy. Tea dragons literally grow tea leaves from their horns, leaves that can be harvested only with a knowing, gentle touch. The tea brewed from said leaves brings back memories: to drink tea dragon tea is to reexperience the past, in quiet reverie. Dragon-keeping and tea-making are slow arts, requiring patience, precision, subtlety, and empathy. There’s a strong suggestion of Japan’s traditional craft (kogei) and art forms, forms bound up in the succession of generations, in the spirit of particular places, and in the relationships between mentors and pupils. Greta comes to know two dragon-keepers: a couple of former adventurers, now settled, who are striving, in defiance of cultural change and time, to keep the tea dragon tradition alive. She also meets the keepers’ shy, enigmatic ward, Minette, a girl who, it turns out, was once a prophet. Love between the two keepers, as well as the possibility of love between Greta and Minette, is romantic and idealized, queer-affirming, and chaste but not timid (i.e. the romance, though never earthy, is more than implicit). Gender conventions are flouted at every turn, albeit gracefully. The book strikes me as aesthetically genderqueer, its characters always beautiful and its art sensuous, yet it’s entirely, as we say, child-friendly: a quiet ecotopia of loving connection and small, tender gestures. Like its dragons, The Tea Dragon Society has about it an air of preciousness and fragility. The story is based on a pretty frail concept—albeit one elaborately explained in the book’s back matter—and readers unmoved by the bonding of dragon and caregiver may find the tale twee and oversweet. The logic of the story’s world frankly seems rigged so that O’Neill’s particular interests, dragons and tea, can together serve as a metaphor for the way that craft traditions preserve cultural memory. There’s a tidiness about the conceit that isn’t quite believable: tea dragon tea leaves only evoke memories shared by dragon and owner, meaning that the dragons do not pass on memories of their own, but only those experienced by the bonded pair of dragon and caregiver. Dragons rarely bond with each other as strongly as they do their caregivers, and so the social lives of these creatures are bound up in the dyadic closed circuit of dragon and owner. This is a tad too perfect, I’m tempted to say—something like a cat-lover’s daydream. In that sense, The Tea Dragon Society hovers between a credible fantasy world and an indulgence as delicate as spun glass. (It’s easy to be cynical about a story in which petting, pampering, and bonding with small, cute creatures makes everything happen.) Yet the pairing of Greta and Minette—one a crafter of memorable things, the other a fallen prophet who has lost most of her memories—gives the theme of remembering a special urgency, and the bonding of the two makes for an unusual love story. Further, O’Neill’s cartooning, especially her delineation of form through color, creates an immersive visual world that is delightful to visit. The sequences of shared memory include some wonderfully organic layouts, and the book is a treat to page through and reread. Finally, I have to admire the book’s determined emphasis on working and making, so different from what we’ve been conditioned to expect from fairy tales. I am perhaps too old and curmudgeonly for the story of The Tea Dragon Society. I admit, I’d like a world that resists and confounds its characters a bit more, something spikier and less comforting. But I’ll be sure to queue up for O’Neill’s next book (reportedly due out soon). She has the power of worldmaking and her narrative drawing is clear, graceful, and transporting. One of the charms of comics is the way the form invites us into private worlds, and The Tea Dragon Society does that beautifully.

0 Comments

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

Archives

June 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed