|

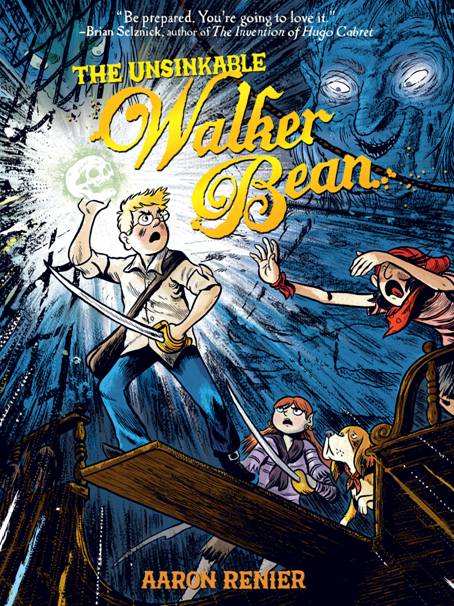

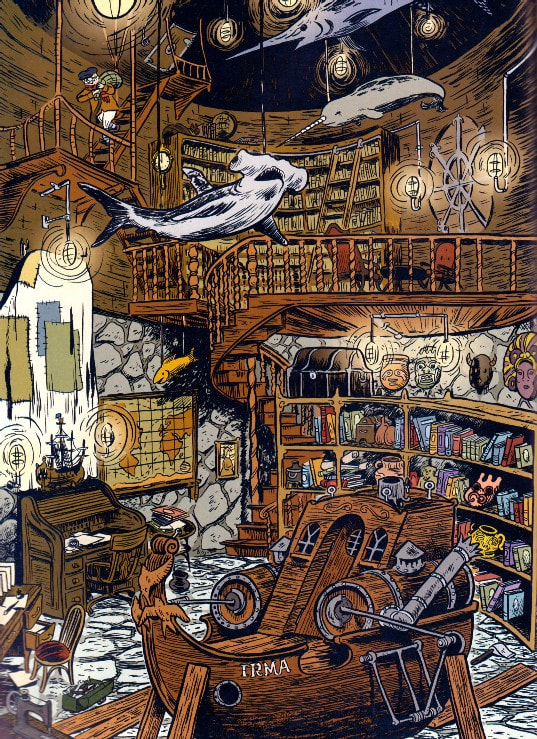

The Unsinkable Walker Bean. By Aaron Renier. First Second, 2010. ISBN 978-1596434530. 208 pages, softcover, $15.99. Colored by Alec Longstreth. (This review originally ran on the now-defunct Panelists blog in June 2011. I've revived it here and now because a sequel to Walker Bean is promised this fall. Ever the fusspot, I have not been able to avoid the temptation to trim and update, albeit slightly. - CH) Piracy on the high seas—storybook piracy I mean, the kind we know mostly from echoes of Stevenson and Barrie—remains an adaptable, nigh-bottomless genre. The piratical yarn lends itself to the dream of an infinitely explorable world, to lusty romance, oceanic myth, and shivery deep-sea terrors, all of it salted with enough bilge, filth, and real-world cynicism to sell even the flintiest skeptic. The golden age of Caribbean piracy, which even as it happened was a set of facts angling to become a myth, helped redefine the pirating life as radically democratic, an anarchic space of freedom—ironic, since it grew out of colonialism and the Thirty Years’ War. That age bequeathed us a roll call of larger-than-life persons, Calico Jack, Anne Bonny and Mary Reade, Blackbeard, and the rest: real-life opportunists from whence Stevenson distilled his great, demonic “Sea-Cook,” Long John Silver, Treasure Island’s indelible villain. Silver’s slipperiness lives on, I suppose, in Johnny Depp’s Jack Sparrow, ever scheming, ever sidling away to scheme another day. Pirates of the Caribbean reinvigorated the old genre, but with a heaping dose of hypocrisy. For example, in Bruckheimer, Verbinski, and Depp's third Pirates film (2007), the multinational juggernaut that is Disney pits globalization, in the person of the über-capitalistic East India Company, against scrappy piratical “freedom,” represented by Sparrow and his fellow rum-soaked scumbags. Huh? Couched in terms of post-9/11, post-Patriot Act resistance to a neoliberal mercantilist New World Order, that movie of course made shiploads of money. Such irony. So, the myth of the high-seas pirate carries on, its popularity an index of how we feel about the tug o’war between hegemonic authority and the individual will to live and indulge. Cartoonists in particular seem to love pirate tales and other nautical yarns, maybe because such tales make the world feel larger, maybe because they give license for scruffiness and odd character design (think Segar), maybe simply because the high seas invite so much gushing ink. A fair handful of graphic novels from recent times either plunge into the deep sea or sail off to faraway places: Leviathan, That Salty Air, Far Arden, The Littlest Pirate King, Blacklung, Set to Sea, et cetera (I bet readers can name a few others). Aaron Renier’s The Unsinkable Walker Bean (released, what, eight years ago now?) dives into the genre with a hectic, dizzying 200-page story and a surplus of delicious inky craft. Written and drawn by Renier and colored by Alec Longstreth, Bean is a beautiful, odd book aimed squarely at young readers, the first of a promised series that, it seems to me, aims to mix a carefully rigged Tintin-esque plot with the jouncing unpredictability and eccentricity of Joann Sfar, whose organic approach to both plotting and drawing probably provided inspiration. The materials are familiar enough, but the execution is, wow, crazy. The results strike me as imperfect but delightful. Walker Bean (a cartoonist’s surrogate?) is an unlikely pirate: a nervous, sensitive boy prone to doodling and mad invention, slightly pudgy and bespectacled to make him seem an unexpected hero. His emotions are worn near the surface. The plot tests his ingenuity and bravery, offering plenty of swashbuckling and catastrophic violence in the bargain. It’s sometimes bloody and boasts some real scares. Walker’s world looks like a farrago of eighteenth and nineteenth century elements—costume, settings, ships—but frankly it’s unreal, a synthetic alternate world. Per the map on the frontispiece, that world is like a distorted view of ours but bears fanciful names (e.g., Subrosa Sound, the Gulf of Brush Tail, and cities like New Barkhausen and Tapioca) alongside real ones like the Atlantic and Mediterranean. Anachronisms abound, such as a middle class child’s bedroom casually appointed with books. Stops along the way, such as the colorful port of Spithead, teem with diverse character types who lend the storyworld a distinctly postcolonial vibe. The plot, a mad, churning mess, begins with mythical backstory: a child’s bedtime story about the destruction of Atlantis. Then it veers sharply into pure breathless adventure. Young Walker, to save his ailing grandfather, must brave the high seas in order to return a maleficent artifact to its home in a deep ocean trench. That artifact is a skull of pearl formed in the nacreous saliva of two monstrous sea “witches”: huge lobster-like monsters who caused Atlantis’s fall. The skull is itself a character, evil, cackling, and seductive. One glimpse of it can send a person into shock or even death. Walker’s grandfather, an eccentric, bedridden admiral, entreats the boy to dispose of the skull, while Walker’s father, Captain Bean, a vain, greedy fool, plots to sell the skull for maximum profit, egged on by one “Dr. Patches,” a fraud and a fiend. The action, which zigzags unpredictably, includes long stretches on a pirate ship called the Jacklight. There Walker becomes an unwitting crew member, working with a powder monkey named Shiv and a girl named Genoa—an able thief and fighter who more than once nearly kills Walker. That's as close as the book gets to the excitements of courtship. The pearlescent skull is said to be a source of great power, of course, but keeps tempting would-be possessors to their doom (there’s a strong hint here of Tolkien’s one Ring). Donnybrooks and sea battles alternate with creepy scenes of the skull exerting its influence and big, splashy encounters with the horrific witches. Pages vary from minutely gridded exercises to explosive full-bleed spreads. Plot-wise, there are double-crosses, shipwrecks, and weird critters aplenty, a burgeoning cast of supporting players, and moments of tenderness, confusion, and self-realization. Walker, Gen, and Shiv are all well realized. Walker himself becomes the true hero that the title promises. In the end, things are resolved but other things left open, setting up Volume Two. Renier has not worked out his story perfectly. Honestly, I didn’t retain most of the plot details after reading through the first time; the story ran by me at a mile a minute, and I couldn’t catch it. The plot twists confusingly like a snake underfoot, and logical stretches are many; even for a pirate yarn, the book strains belief. At one point, the remains of a smashed ship conveniently drift into port. At another, the Jacklight, having been completely wrecked, is rebuilt and transformed into an overland vehicle (with wheels) in the space of a single day. In short, Renier leans on plot devices that don’t convince. What’s more, the storytelling is at times more exuberant than clear; certain double-takes and surprises confused me. Pacing and story-flow sometimes hiccup. What we’ve got here is a patently rigged plot set in an overstuffed story-world that is still in the process of being worked out. Walker Bean is a generous story, almost risibly full, but sometimes it's hard to believe. Ah, but how it testifies to the love of craft! The book’s colophon describes in detail Renier’s process of drawing and hand-lettering (on good old-fashioned Bristol board) and then the shared process of coloring (where the digital takes over). All tools and techniques are duly described, even razor-work and the use of Wite-out to vary texture. The descriptions are aimed at any reader; no prior knowledge of technique is assumed. It’s as if Renier and Longstreth wanted to let young readers in on their trade secrets. The book’s coloring, it turns out, began collaboratively: Using some old, faded children’s books for inspiration, Aaron and Alec created a custom palette of 75 colors, which are the only colors used in this book. Coloring a big book is easier when one has only a limited number of colors to choose from, and it makes the colors feel very unified. The results do exhibit an aesthetic unity, without disallowing the occasional eruption of tasty graphic shocks. In any case, the blend of line art and color—handiwork and digital—is gorgeous. Renier, if not yet a surefooted storyteller, is a terrific cartoonist. Vigorous brush- and pen-work, lush texturing and atmosphere, dramatic staging, complex yet readable compositions, and even formalist games—all these are in his ambit. Examples are legion. For instance, check out this panel depicting a bumpy ride: Or this much quieter one, depicting a secret hideout: Renier’s commitment to the work and talent for conjuring strange places and characters show in every page—and every page is different. This is first-rate narrative drawing, stuffed with beauty and promise; it takes the gifts shown in Renier’s first book, Spiral-Bound, and boosts them to a new level. Finally and most importantly, Walker Bean has soul. It makes room for emotional complexity. Minor epiphanies and finely observed silences, scattered across the book, make it much more than an opportune potboiler. Behind the book is a thumping heartbeat that testifies to a reckless love of comics and adventure. This is a yarn without a whiff of condescension: mad, high-spirited, and cool. (Volume Two is due this October. Hmm, what difference will eight years make? Also, note that KinderComics will be on summer break between now and Monday, August 20, 2018.

0 Comments

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

Archives

June 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed