|

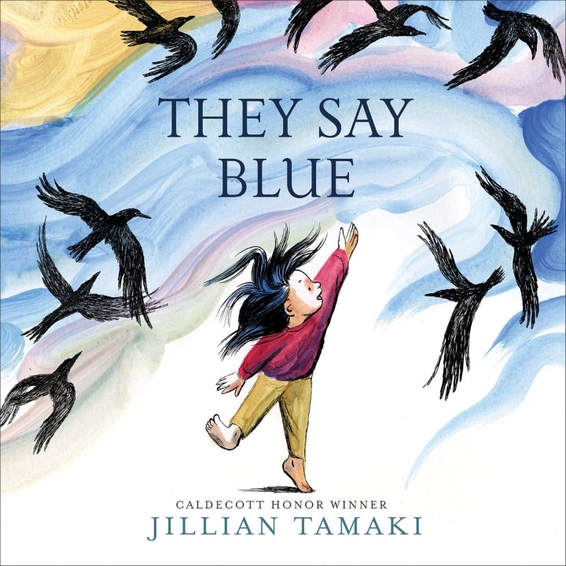

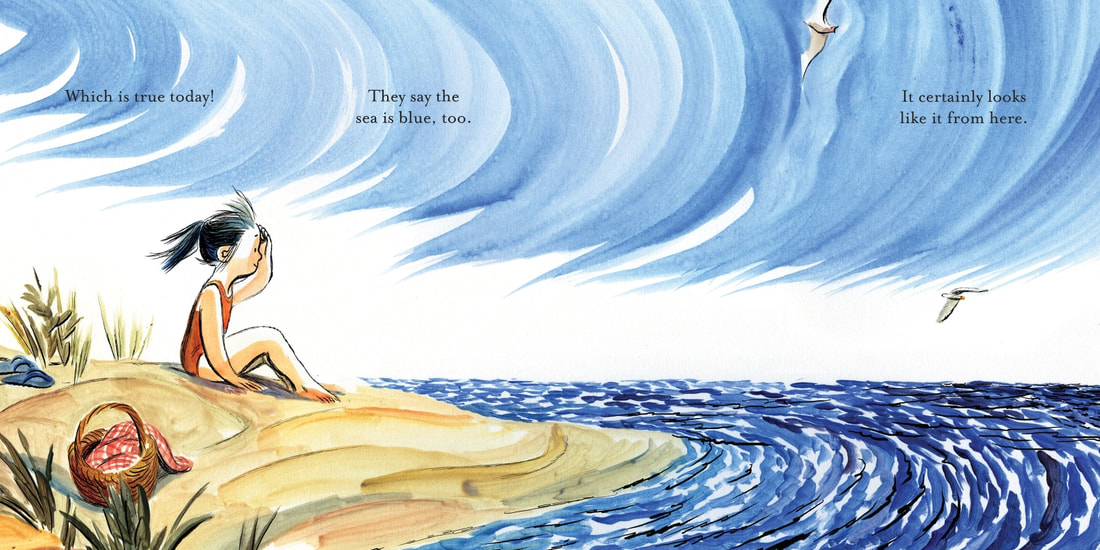

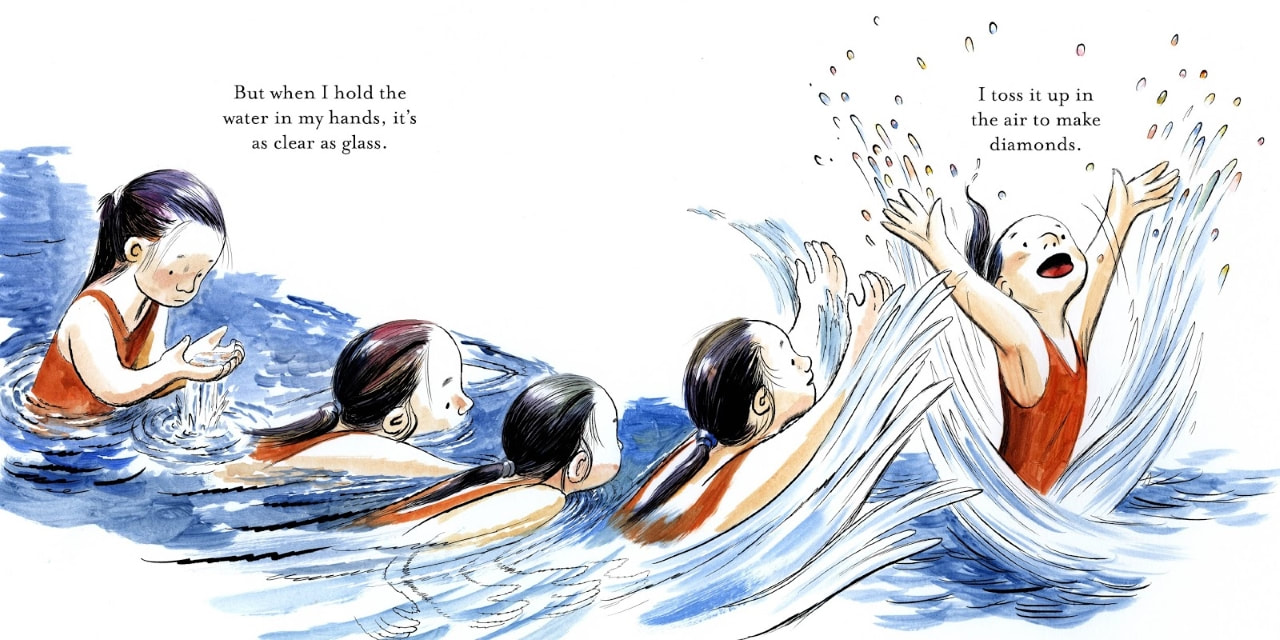

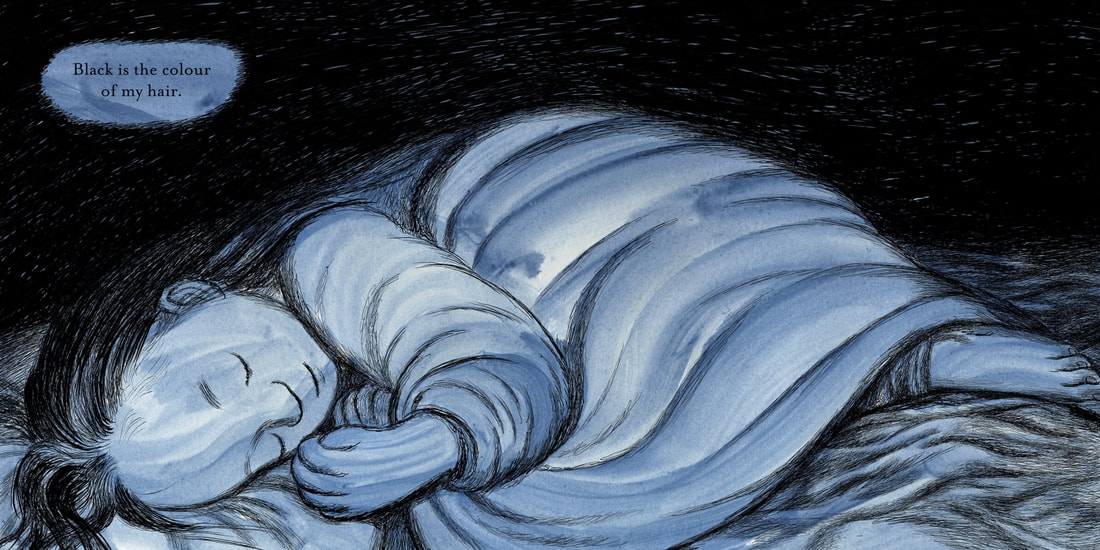

They Say Blue. By Jillian Tamaki. Abrams Books for Young Readers, March 2018. ISBN 978-1419728518. $17.99, 40 pages. Jillian Tamaki (Skim, This One Summer, SuperMutant Magic Academy, Boundless, much more) has just done her first children's picture book, They Say Blue. It's a dream: a lyrical, drifting book about seeing and not seeing, about a world of colors, about raw perception but also how we reflect upon and try to make sense of our perceptions. Painted in flowing acrylics on watercolor paper, with overlays of inked drawing via Photoshop, They Say Blue consists almost entirely of full-bleed double-spreads dotted with short, vigorous bursts of text. Lavishly illustrated yet sparsely written (roughly twoscore sentences run through its twoscore pages), it is less a storybook than a visual poem, liquid, freely expressive, and unpredictable. It focuses on the aesthetic sense and restless intelligence of a young girl with an artist's eye, for whom ordinary things can be extraordinary. The young narrator treats common sights and happenings as festivals of color, light (or darkness), and warmth, even as she sees the world around her in a here-and-now, everyday sort of way. She comes across not as some idealized Wordsworthian poet-child (though the book does partake of that spirit, a bit) but as a believably curious and engaged girl. Wonder and watch are key words, and wonder well describes my own response to the book. In other words, They Say Blue is a credible and lovely evocation of a child's creative eye and voice. It recalls, for me, the pithy matter-of-factness of Krauss and Sendak's A Hole Is to Dig, or the free-associative riffing of Crockett Johnson's Harold. It's more visually extravagant than either of those, though, recalling how the modernist here-and-now picture books of the early 20th century, the kind championed by Lucy Sprague Mitchell and Margaret Wise Brown, captured children's daily lives and intimate concerns with simplified, streamlined prose-poetry yet also, often, with rapturous, brilliant images. Tamaki is working that same ground, in (as she has said) a quite traditional way. It's a tradition less about story than about a child's looking and thinking, that is, about being in the world. I think of Brown's books with Leonard Weisgard (such as The Noisy Book, The Little Island, and The Important Book) or of course her work with Clement Hurd (most famously Goodnight Moon) -- books about ordinary sensations or the reassuring rhythms of life. They Say Blue, you can tell by its very title, is about the young girl stacking up what "they" say against what her own experience tells her. It begins with a nonfigurative spread of pure blue -- a field of overlapping brushstrokes -- and the simple observation, They say blue is the color of the sky. But, as we turn the page, then the narrator measures what "they say" against her own vision, in this glorious spread: Turning again to the next spread, we see the girl swimming through, gazing at, and splashing in seawater: five drawings of her combined into a single image. In picture book critics' parlance, this is a clear case of simultaneous succession or continuous narrative -- but to me the important thing is that it shows the girl's immersion in experience, and her way of questioning what she is told, but then also reveling in what the world gives: But just as important as these rhapsodic passages are subtle ones that chip away at the idealization of childhood. My favorite is a series of two openings that together raise up but then undercut an idyllic fantasy. The first shows our narrator sailing in an imaginary boat over a field of grass "like a golden ocean" (more simultaneous succession: delightful movement). The next, though, shows a fairly bleak, rain-sogged landscape and the girl trudging homeward through foul weather, dragging her backpack behind her against a sky of grim clouds and dull grass. She concedes, It's just plain old yellow grass anyway. I can almost hear the weariness in her voice. Thankfully, it doesn't last, but I love the way Tamaki works these bum notes into the book. Make no mistake: They Say Blue is gentle. It is affirming. But I like the way it registers moments of doubt, bewilderment, and everyday muddling. Its poetry is an everyday sort of poetry, as in, Black is the color of my hair. / My mother parts it every morning, like opening a window. Opening a window on new ways of seeing familiar things is exactly what the book does. Many comics artists struggle when moving into picture books, but They Say Blue engages picture book form and tradition knowingly. Tamaki's recent interview with Roger Sutton at The Horn Book shows how well she knows the form, and artistically she takes to the picture book as if it were an answer to a question she has been asking. In a conversation with Eleanor Davis at The Comics Journal last summer, Tamaki admitted that "I can feel increasingly confined by the image part of comics," and reflected that, at least "for more commercial works, the images [in comics] need to be a lot more literal." She described herself as trying to "stretch that word-image relationship." More recently, in an interview with Matia Burnett at Publishers Weekly, Tamaki contrasted the experience of making comics with the experience of making picture books: They’re pretty different. The poetry and distillation of kids’ books, in word and image, is a completely different challenge. A lot of comics [work] is just grinding out pages, if the images communicate what’s happening, that’s usually good enough in a pinch. A picture book’s images have to evoke, which is much more ephemeral. My sense is that They Say Blue exercises a different part of Tamaki's artistry, while still being very clearly a Jillian Tamaki book. I'm glad. The book is beautiful, a work of deft visual poetry. It confirms that, as Eleanor Davis put it, "there is no one who is better."

0 Comments

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

Archives

June 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed