|

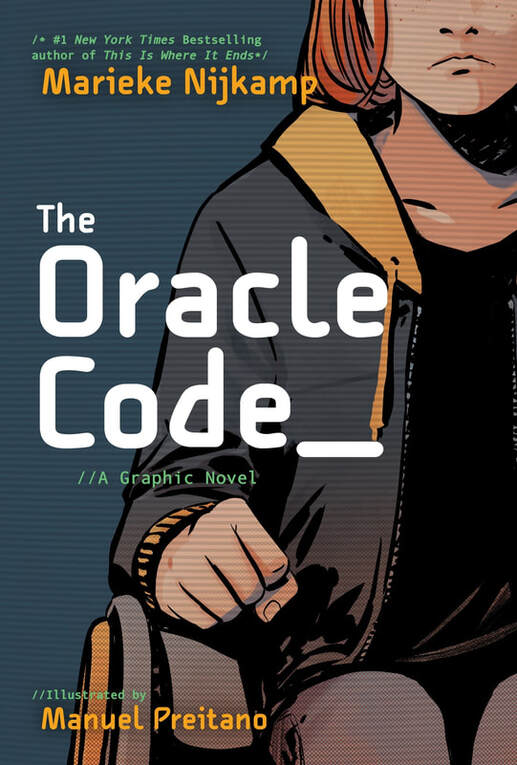

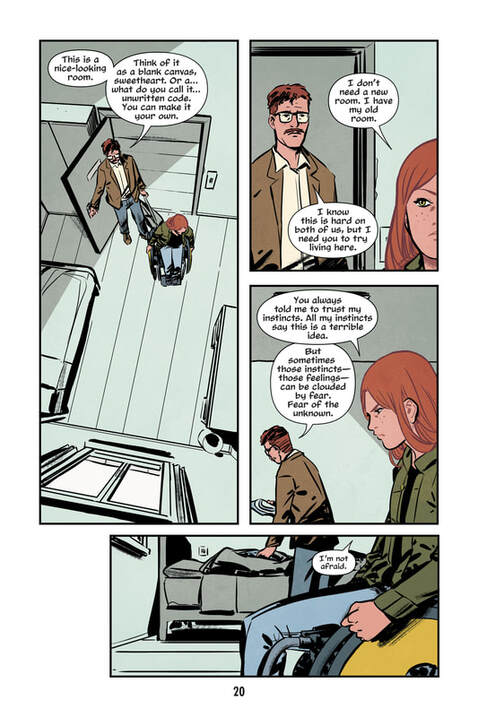

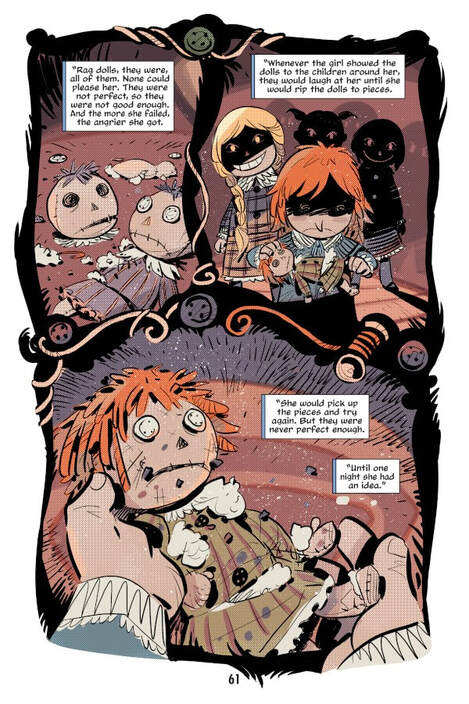

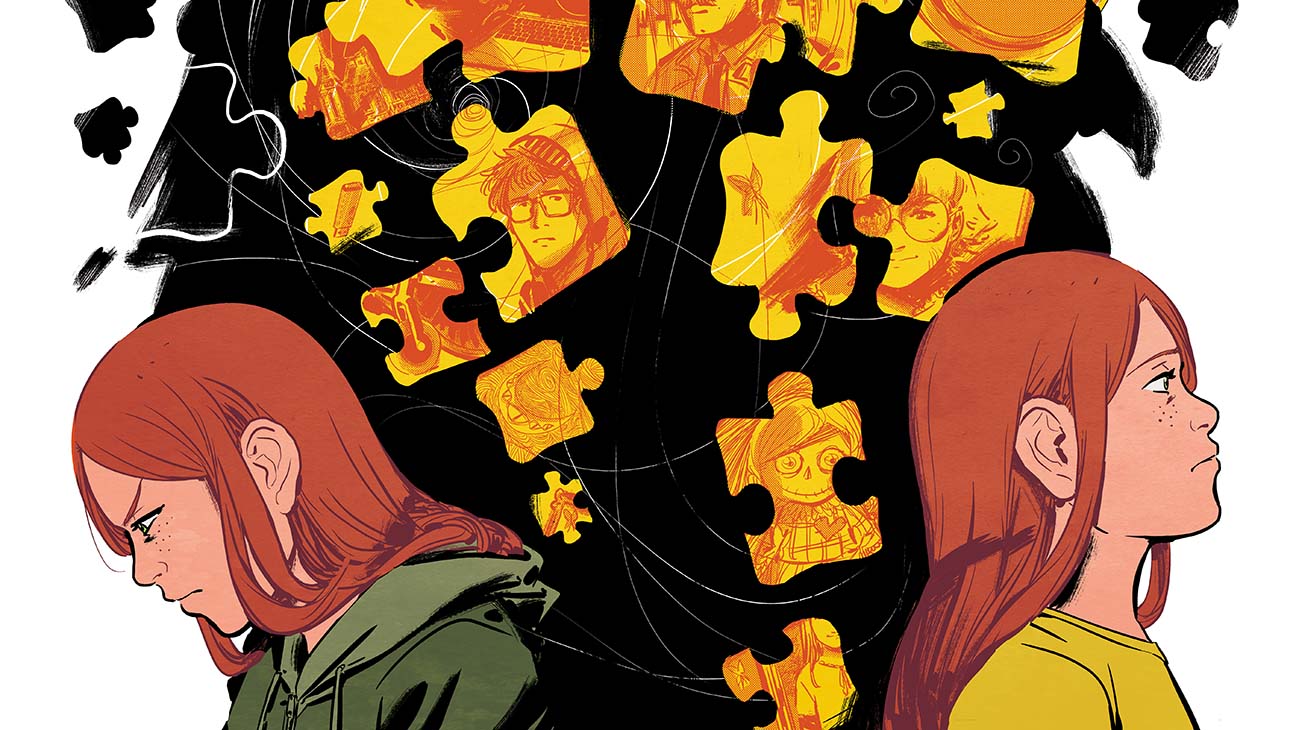

The Oracle Code. Written by Marieke Nijkamp; illustrated by Manuel Preitano; colored by Jordie Bellaire with Preitano; lettered by Clayton Cowles. DC Comics, ISBN 978-1401290665 (softcover), 208 pages. US$16.99. March 2020. (This is the second in an occasional series reviewing children’s and Young Adult graphic novels from DC. See the first here.) Paralyzed by a gunshot wound, brilliant young hacker Barbara Gordon (daughter of Gotham’s police commissioner) undergoes rehabilitation at the so-called Arkham Center for Independence — which, surprise, turns out to be a sinister place, a haunted house even, from which patients keep disappearing. Though traumatized, and at first resentful and alienated, Barbara gradually bonds with other patients, and together they form a team to unravel Arkham’s dark secret. This DC graphic novel does not appear to mesh with any version of DC continuity, and its Barbara Gordon differs sharply from previous Barbaras (Batgirl or Oracle). In fact, its DC-ness is nominal, and could be erased with a few minor edits. It’s not a superhero story in the usual sense. Rather, it’s a Young Adult thriller that follows many of that genre’s conventions: young people up against corrupt adult institutions, fighting with official powers, fighting for self-definition, testing their mettle with no outside help. It’s also grounded in an intersectional and community-oriented disability politics that makes it stand out among DC books. Writer Marieke Nijkamp is an acclaimed author of YA thrillers (e.g., This Is Where It Ends), editor of a disability-themed YA anthology (Unbroken), and advocate for greater diversity in children’s and Young Adult publishing (she served as a founding officer of We Need Diverse Books). The Oracle Code’s plot seems to have been informed by her experience living in a medical rehabilitation facility as a teenager. Her loner hero, Barbara, eventually enters into community, and, with her team, emphatically rejects the idea of being “fixed” (echoing Nijkamp’s criticisms of the trope of curing disability). The book’s politics are obvious and central, and some minor characters and relationships seem designed to make points — or to serve merely as hurdles to Barbara’s ferocious drive. The plot, I think, rushes to a too-sudden conclusion; I can see the story’s somewhat familiar shape from far off. Barbara herself, though, is a distinct character, and the book gives her time and space to be properly angry. If the book preaches, it doesn’t preach to Barbara. Also, the wrap-up wisely lets certain resolutions stay ambiguous; this is no facile overcoming narrative in which all things are made better. The book reflects on the healing value of dark stories — through a series of unsettling embedded tales, like bedtime stories — and itself does not shy away from trouble. The Oracle Code, in sum, is a designedly Young Adult novel that reflects and capitalizes on the disability politics always implicit in the Oracle character. Visually, The Oracle Code wavers between arid daytime plainness — perfect for a medical facility — and darkly atmospheric nighttime scenes. Illustrator Manuel Preitano favors a naturalism that, for me, recalls the post-Mazzucchelli work of David Aja (though without Aja’s drastic stylization and formalist invention). The intentionally limited color palette (colors are credited to both Jordie Bellaire and Preitano) pits vivid yellow-orange and nocturnal purple-blue against drab olive and icky, hospital-bland greens. Insipid, textureless rooms — like the flat, medicalized interiors we all know, presumably lit by fluorescents — clash with densely shadowed scenes defined by slashing swathes of black and vigorous dry-brush technique. Bright jigsaw puzzle pieces stand out against the general gloom and serve as a braided visual device: a multivalent symbol that variously signifies trauma, fragmentation, reassembly, accomplishment, and, of course, mystery-solving. The layouts are dynamic, shifting, yet steadily rectilinear, except for the embedded “bedtime” stories, which boast curving, swirling panel shapes and a contrasting, cartoonish style. This novel is, as far as I know, Preitano’s longest sustained work for the US market (he has also worked on the series Destiny, NY and several comics for Zenescope), and departs from the sometimes lurid retro aesthetic of his illustrations for the Vaporteppa fiction line, in his native Italy. This looks like a big step forward for the artist. On balance, The Oracle Code shows the potential of YA fiction that happens to be set in DC’s story-world. It’s more self-contained, and more attuned to the conventions of YA fiction, than I had expected. To me, these are good things. One thing gets to me, though: despite the signs that this book is a rather personal work for Nijkamp, it is copyrighted solely in the name of DC Comics — that is, it’s work for hire (though it bears about as much resemblance to prior Oracle stories as, say, Neil Gaiman and company’s Sandman bore to prior Sandmen). I think that’s a shame, and, honestly, this is one reason I have not been able to muster great enthusiasm for DC’s work with YA and children’s authors. As long as DC graphic novels are centered on company IP and the creators are wholly dispossessed of any equity in the work, as long as DC persists in these damaging comic book industry practices, the promise of its young readers’ line will be dampened. The Oracle Code is very unusual for a DC comic — its focus on a non-superpowered community of young women, and willingness to highlight a young woman’s anger and power, are laudable — but it’s still shackled to DC’s old way of doing things.

0 Comments

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

Archives

June 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed