|

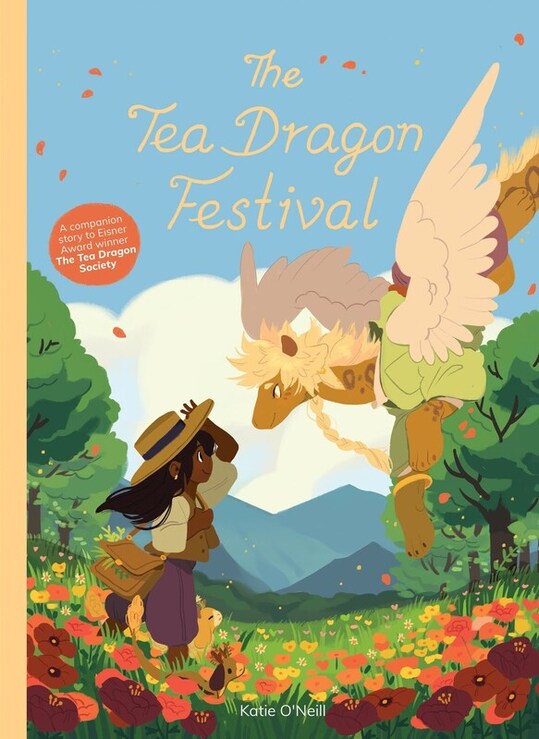

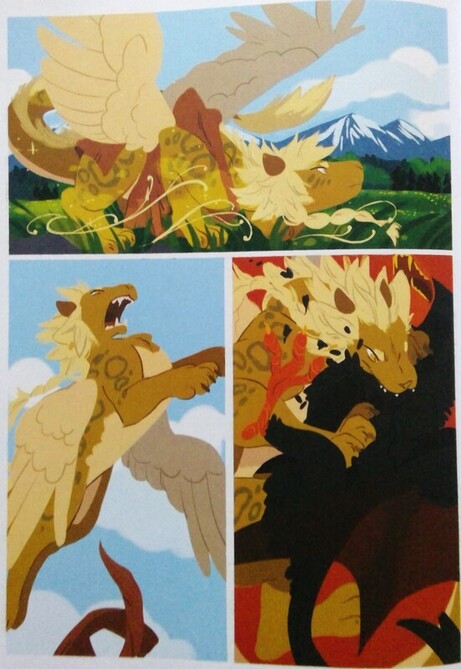

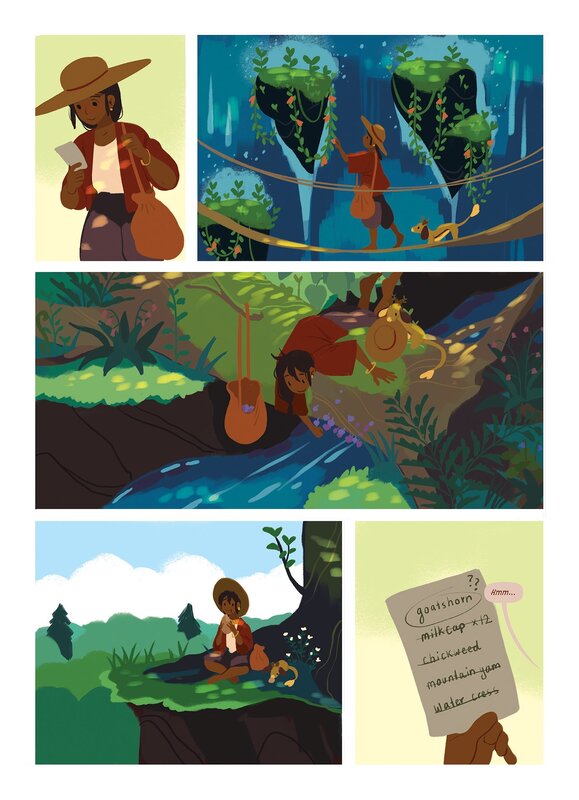

The Tea Dragon Festival. By Katie O’Neill. Oni Press, ISBN 978-1620106556 (hardcover), 2019. US$21.99. 136 pages. I read The Tea Dragon Festival during an early morning idyll, propped up in bed with a cat curled up on my lap (our cat Max likes to hang with us when we read). That sounds about right — it’s that kind of book: tranquil, comforting. A purring cat, basking in a morning ritual, is a pretty good stand-in for the semi-domesticated “tea dragons” that populate its world. In fact, here on KinderComics I described this book’s predecessor, The Tea Dragon Society (2017), as an “idyll full of greenness and life” and a “cat-lover’s daydream.” The same goes this time. The biggest problem I had with this sumptuous book was reading it by diffuse sunlight: O’Neill’s occasional layering of dark or muted colors posed a challenge to my eyes; I couldn’t make out certain expressions and overlapping shapes. I ended up having to turn on my reading lamp and point it directly at the pages — then the expressions popped. So, I recommend reading The Tea Dragon Festival by strong light; then you’ll really get to see O’Neill’s ravishing color work. When well-lit, the book fairly glows. Cover blurbs describe Festival as warm, charming, and gentle. Again, that sounds right. The story skirts pain and hardship; though it evokes some subtle melancholy, its characters are not burdened with difficult ethical decisions or hard losses. The vibe is green, dreamlike, and utopian (with the now-expected traces of Miyazaki). The one potential source of serious conflict appears and disappears in a handful of pages. In fact, the book is so quiet and anodyne that it’s quite a surprise when a fight briefly breaks out: Like its predecessor, Festival takes place in an eco-topia: an idealized rural culture defined by caring community and respect for traditional crafts. The story, again, focuses on a growing girl who is learning a craft — in this case, cooking — and her interactions with dragons — this time, not just miniature tea dragons but also a full-blown, shape-shifting, often humanoid dragon. This dragon, Aedhan, considers himself the appointed protector of the girl, Rinn’s, village, but has been waylaid by a magical, eighty-year sleep, from which he has only just awoken. He is filled with regret for the years he has missed. Rinn takes responsibility for helping Aedhan get to know her people and acculturate to village life — so, once again, the story revolves around the sharing of memories, as Aedhan moves from outsider to trusted villager. Though longer and more ambitious than the first book, then, Festival takes up the same concerns and exhibits the same qualities. I like O’Neill’s work for emphasizing, as I’ve said before, loving connection and tender gestures. But I have to repeat another observation too: this book’s delicacy left me wanting more complication, more trouble. I wanted a harder story, something that would show the characters’ values when put to a fiercer test. It’s easy to love the world O’Neill has created, one of sharing and openness, indeed a queer, feminist, anti-capitalist utopia. Clearly, she herself loves the world and its characters. I particularly like the inclusion of signing (American Sign Language) as a plot element, which sharpens O’Neill’s already impressive sense of (in this case literal) body language. The story, though, gives no sense that the apple cart has ever been upset, or the people’s equanimity challenged, by the ordinary work of survival. O’Neill seems to prefer quieter dilemmas, smaller stakes. Festival is sweet and affirming, but its plot evanesces soon after reading, leaving behind an impression of a personal wonderland, exquisitely tended and mostly about the pleasure of its own rendering. I’ll happily read more by O’Neill: she’s a gifted cartoonist and book artist. Each time I read her, though, I become terribly aware of my own cynicism. Harrumph!

0 Comments

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

Archives

June 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed