|

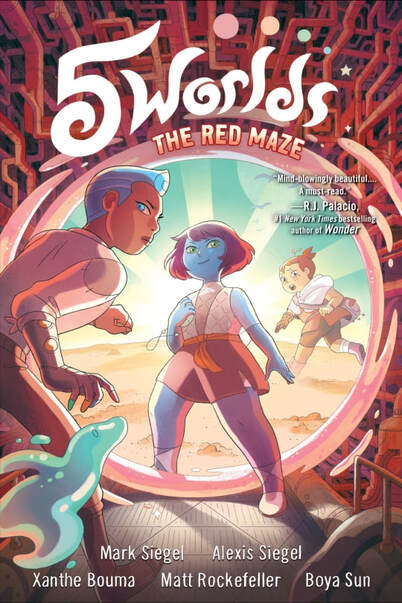

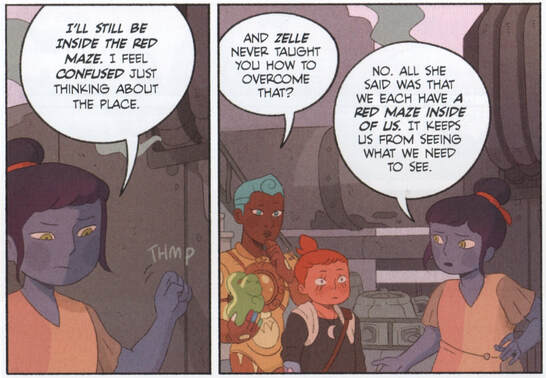

5 Worlds: The Red Maze. By Mark Siegel, Alexis Siegel, Xanthe Bouma, Matt Rockefeller, and Boya Sun. Random House, May 2019. Paperback: ISBN 978-1101935941, $12.99. Hardcover: ISBN 978-1101935927, $20.99. 256 pages. 5 Worlds — the epic science fantasy series by brothers Mark and Alexis Siegel and the artistic team of Xanthe Bouma, Matt Rockefeller, and Boya Sun — has been overstuffed with invented worlds, scenic wonders, and dizzying plot twists from the start (that being 2017’s The Sand Warrior and its 2018 followup, The Cobalt Prince). The series has bounded from one setup to another with a breathless energy and worked up a sprawling, spiraling plot. Its delights are many, but its confusions too, inspiring mixed reviews from yours truly (the first here, the second here). It’s a labor of love, obviously, and the complex collaboration behind it has wrought visually seamless results: a remarkable artistic and editorial feat. There have been times, though, when 5 Worlds has seemed to rush narratively from one thing to another: this world, and then that; a tip o’ the hat to this influence, then that one; another disclosure of tangled backstory, another "huh?" moment. I’ve sometimes wondered if the influences were going to cohere into something distinct, and if the long game wasn’t getting in the way of the individual volumes. But no longer. The recently-released third book, The Red Maze, gathers up, extends, and deepens 5 Worlds with confident character and thematic development, careful pacing, and a troubling relevance. It’s the strongest, most sure-handed of the three books to date, also the sharpest and most topical. An ambitious entry, it gains depth on rereading, while still pulling this reader eagerly on, toward the next volume. Now we’re talking. Briefly, 5 Worlds depicts a system of five planets (to be visited over the series’s five volumes) that are dying of heat death and can only be saved by the lighting of a series of ancient “Beacons,” one on each world. Each new volume of the series focuses on one of the worlds and uses an integrated color scheme implying the dominant culture(s) of that world. The protagonists, a classic heroic triad, are Oona, trained in the ancient discipline of “sand dancing,” who is tasked with reigniting the Beacons; An Tzu, a street urchin of unknown origins and powers, still coming into his own; and Jax, a sports star and (secretly) an android, though archly nicknamed “The Natural Boy.” Each has an unfolding origin story full of twists and surprises, from Oona’s true heritage (revealed in The Cobalt Prince) to the newfound humanity of the Pinocchio-like Jax (who was waylaid for most of the second book but returns and grows more complex here), to An Tzu’s “vanishing illness” (i.e. disappearing body parts) and newly discovered oracular powers. All three have nonstandard, stereotype-defying qualities and hail from vividly realized cultures (carefully imagined in terms of ethnicity and class). In The Red Maze, all three have arcs, problems, and discoveries, without any one of them being overshadowed by the others. From the book's opening, a frantic action scene that reintroduces Jax, to its final pages, which tease the forthcoming Volume Four, the plot rockets along, and yet, more so than in past volumes, makes room for quiet, character-building exchanges and epiphanies. The Red Maze made me want to reread all three volumes with an eye on that proverbial long game. If the second book improved on the first, this new volume overleaps them both. The Red Maze’s special power comes partly from its pointed political relevance. The book allegorizes the current politics of our world in a way that's pretty much on the nose, and crackles with urgency. At last, it seems that 5 Worlds is discovering (or perhaps I am just belatedly discovering?) its themes, which include, broadly speaking, fighting impending ecological disaster while speaking truth to power, and finding one’s identity in principled resistance without losing the joy of life. The Red Maze depicts its heroes saying "hell no" to the short-sightedness and greed of oligarchs and false populists who have vested interests in denying that anything is wrong. Along the way, of course, it tells multiple coming-of-age stories, as each of our three heroes has self-discoveries to make — but it's the constant backdrop of world-threatening climate change that sharpens everything and raises the stakes. This particular volume takes place on “the most technologically advanced of the Five Worlds,” the supposedly free and democratic Moon Yatta, against the background of, ah, an election campaign that pits the ordinary mendacity of a self-serving incumbent politician against the demonic scheming of a populist gazillionaire challenger, a demagogue boosted by authoritarian media and keen to exploit xenophobia. Both would like to silence our heroes’ message of looming environmental collapse. Basically, we’re dealing with climate change denial here, as well as a stew of political chicanery, nativism, and bigotry. Familiar? There’s more. The Yattan regime, we learn, suppresses a minority of protean “shapeshifters” who have the ability to change bodily form (and gender) but who are subdued by “form-lock” collars (clearly, signs of enslavement). Signs of oppression are everywhere, most obviously in a diverse crew of rebellious street kids who become an intriguing if perhaps under-developed new supporting cast. Despite the kids' help, though, our heroes' attempts to penetrate the industrial complex or “maze” around Moon Yatta’s Beacon come to nothing. So, desperate measures are called for. Jax, athletic superstar, is coopted to play in a much-hyped televised championship that becomes a propaganda coup for the challenger, supported by the obscenely wealthy “Stoak” brothers. And if all that doesn’t come through clearly enough, allegorically, consider this blurb on the book’s inside front cover: ...Moon Yatta is home to powerful corporations that have gradually gained economic control at home and on neighboring worlds... [Its] democratic system of government is widely admired in the Five Worlds, but there is increasing concern that it may be undermined by the political influence of its corporations. Indeed, a cabal of super-rich profiteers, aided by the rantings of a Limbaugh or Alex Jones-like media blowhard, works to undercut the Yattan democratic system. Everything, it seems, is about money, even health care: a hospital scene depicts a boastful, tech-savvy doctor determined to leech every penny from his patients. Other scenes show populist xenophobes towing the oligarchs’ line and condemning the shapeshifters for threatening the social order. Racism and homophobia are implicitly evoked (you have to read between the lines, but what’s there isn’t that hard to see). Unsympathetic readers might call this propaganda, but children's fiction, including fantasy fiction, has always been value-laden if not didactic. My description may make The Red Maze sound less like a story than a screed, but it actually is a story, and a thrilling one, a rattling good yarn. At its heart is a spiritual crisis for Oona: the weight of expectation on her is so great that it crushes her joy in dancing, in using her near-magical art. She falters, bewildered and panicked by the retreat of her powers. (This recalls, for me, Kiki’s temporary loss of confidence and magic in Miyazaki’s adaptation of Kiki’s Delivery Service.) Late in the book, a training sequence, that is, a mentor-mentee sequence, allows Oona — and the story — a calming and refocusing moment, a catching of breath. Thus Oona is able to take a perspective beyond that of the looming crisis, and learn a crucial new power. Her dilemma has to do with finding ways to sustain her spirit in the face of overwhelming environmental and political odds: how do you keep going when things are so terrible? That’s a kind of dilemma, and story, that needs telling right now. Oona's mentor Zelle (one of a long line of mentor or donor figures in 5 Worlds) tells her, “We each have our own red maze. We can be lost there.” What’s needed, Zelle suggests, is joy and inspiration: some delight in the doing, right now, whatever the odds against us. Oona, though, admits that she feels stuck “inside the red maze. I feel confused just thinking about the place.” She has to look for other perspectives on her task, other angles on the problem. Out of that crisis comes the through-line that gives The Red Maze its depth and integrity. This third volume of 5 Worlds makes everything click. It's aesthetically dazzling, of course; 5 Worlds has always been beautifully designed, rendered, and colored. The Red Maze is another master class in revved-up graphic storytelling, the pages at times bursting into frenzied action, during which bleeds, diagonals, and unframed figures spike the book's ordinarily measured and lucid delivery (dig, for instance, the ecstatic climax). The series has always been good at that sort of thing. Yet now 5 Worlds is jelling narratively and thematically. The Red Maze builds smartly on the previous books, and brings fresh nuances to its heroes, growing each into a deeper, more interesting character. The myriad artistic influences are still there, but the world-building no longer feels, say, stenciled from Miyazaki; instead the story-world has gained enough heft and momentum to draw this reader into its own singular orbit. And the stakes feel genuinely high. I expect that, when 5 Worlds is completed, rereading it all and watching it come together is going to be a very rewarding experience. Granted, The Red Maze won't make sense to those who haven't read the first two volumes: though 5 Worlds has a modular structure (one world per book), it is definitely one continuing story, not an episodic series. (Start with The Sand Warrior.) But this third volume is a terrific reward for those who've been following along: a timely, urgent, artfully layered adventure. I think we’re looking at some kind of monument in the making. Random House provided a review copy of this book.

0 Comments

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

Archives

June 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed