|

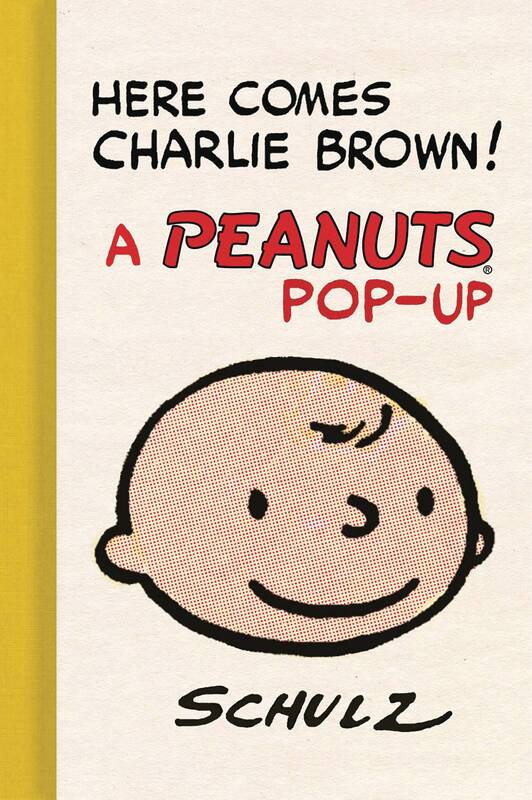

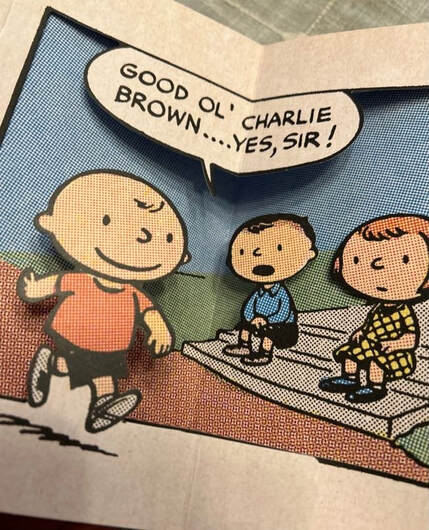

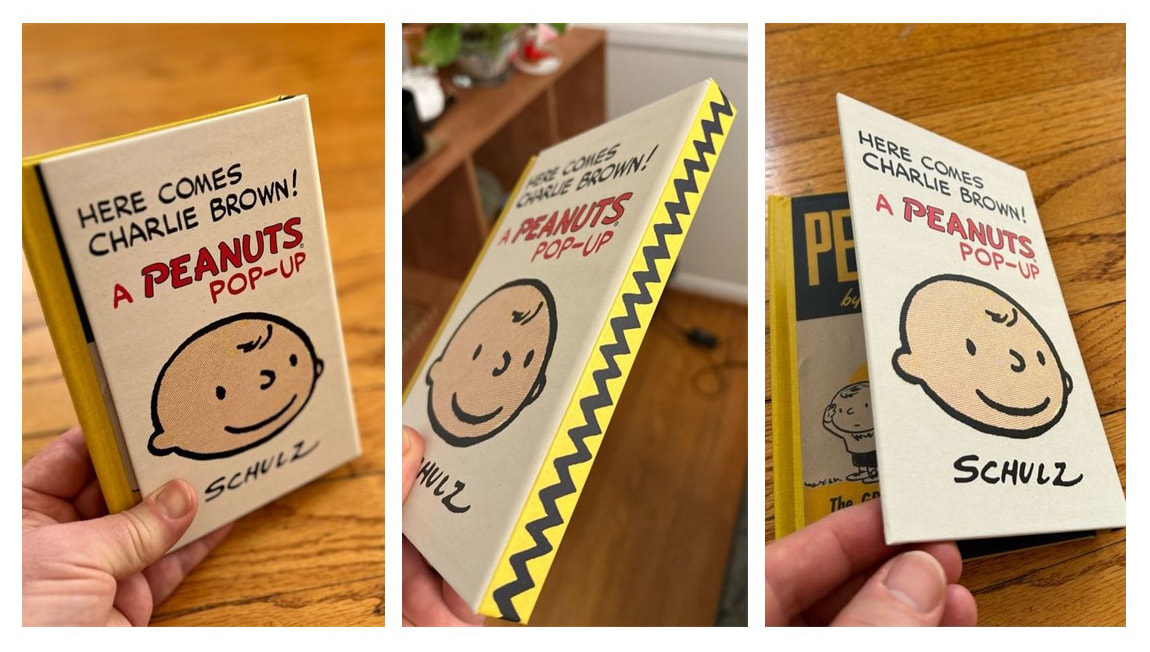

Here Comes Charlie Brown! A Peanuts Pop-Up. By Charles M. Schulz. Paper engineering, coloring, and afterword by Gene Kannenberg, Jr.; design by Shawn Dahl; front cover design by Chip Kidd. Abrams ComicArts, ISBN 978-1419757785, March 2024. US$16.99. 12 pages, hardcover. There are gift books, and then there are gift books. If there is a Peanuts fan in your life, this is for them, full stop. It's definitely for me! This is hardly an objective review. For one thing, I'm a gushing fan of vintage Peanuts stuff. For another, Here Comes Charlie Brown! was brainstormed and engineered by my colleague Gene Kannenberg, Jr., one of my oldest and dearest friends, with whom I've shared countless hours geeking out over comics and bookness. Gene helped me get through grad school with his sympathy and brilliance, and he just keeps on giving! So, I won't pretend to be disinterested this time. Here Comes Charlie Brown! is an ingeniously engineered pop-up book consisting of, mostly, the first-ever Peanuts strip, originally published on October 2, 1950: the beginning of Charles Schulz's famed half-century run. So, it's basically a deluxe reformatting of a single four-panel comic strip. Physically, it resembles a chunky board book, and has just six openings (the last one devoted to a revealing and insightful afterword). Gene K. has colored the originally black-and-white strip, in a subtle, slowly darkening way that matches its acerbic punchline. The coloring, based on Ben-Day dots, feels vintage — as Gene notes, a digital equivalent of mid-20th century comics coloring. What really gets me is the layering of the images: each pop-up opening has three layers, or depths, and Gene shifts the layering with every panel, to, as he says, "amplify" the power of Schulz's original. This effect seemed subtle at first, but becomes more and more forceful with each re-reading. It's super-smart and very much in tune with the complex tone of Schulz's humor. All this may sounds simple — a book re-presenting a single short strip — and it's true that my first reading of the whole book took only a few minutes. Yet Here Comes Charlie Brown! is one of those books that makes you self-conscious about being a book user, and even about the whole idea of bookness. It intensifies the comic strip reading experience while making me think about how books are put together. The overall design is by Shawn Dahl (who often designs for Abrams and has done several books with Mutts creator Patrick McDonnell), and it's striking. The book's heavy cover actually wraps around and encloses the whole thing, making it feel less like a conventional book than a gift box; that is, the back cover reaches around to the front, creating a front flap that, counter-intuitively, you have to open from left to right. I cannot describe it well, but perhaps some pictures will help: This has the effect of creating a sturdy shell for the finely wrought contents inside, strengthening what could otherwise seem delicate. The hand feel of this chunky, pocket-sized object is exquisite. What's more, the visual design of the book is spot-on, with a front cover that consists almost entirely of elements lifted from the original strip. Even Schulz's signature seems to have been repurposed from that strip. So, there are a number of visual rhymes and reinforcements in the total package. Everything resonates. It's a delightful exercise in pure bookness. Here Comes Charlie Brown! is more than a decorative novelty. It's an interpretive act: a sensitive reading and reframing of Schulz's original. I can't stop paging through it! I dearly hope it will be the first of a series.

1 Comment

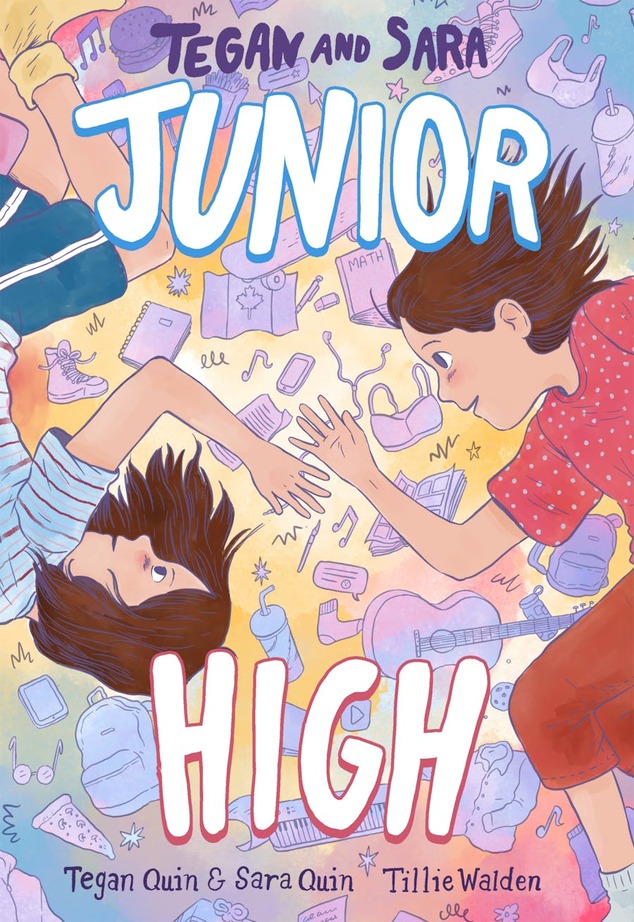

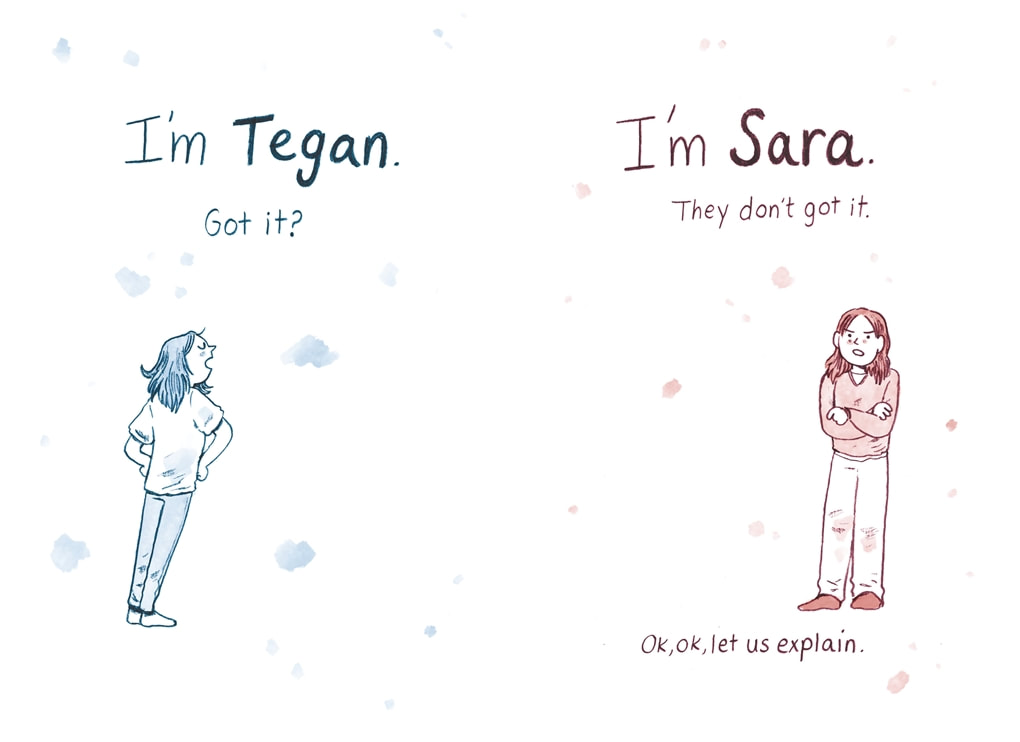

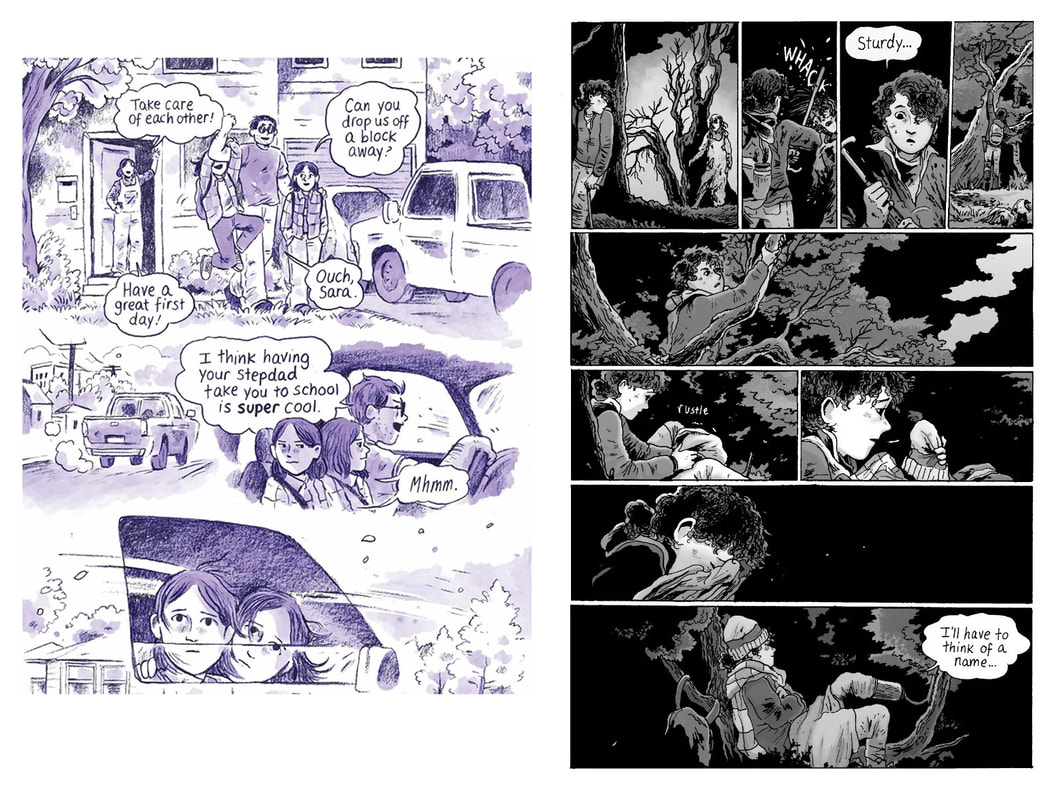

Junior High. By Tegan Quin and Sara Quin (scripting) and Tillie Walden (art). Farrar, Straus and Giroux, ISBN 978-0374313029, 2023. US$14.99. 304 pages, softcover. Tillie Walden strikes again! As ever, I'm excited to see a new book by Walden, one of America's most gifted comics artists and a particular favorite of KinderComics. I realize that this blend of fiction and autobiography (as the publisher calls it) is more likely to be billed as a true-to-life personal story by indie-pop stars and identical twins Tegan and Sara. Of course. Yet I have to admit that, for me, it began as a Tillie Walden book. It was Walden's name that got me to perk up and pay attention, and for that I'm glad. Turns out it's very well-written by Tegan and Sara, and yet another interesting departure for Walden. By now, Walden is hopefully no longer burdened with the wunderkind reputation that seemed to stick to her for her first several books. I mean, that rep was understandable — she was amazingly young for a graphic novelist, it seemed, and fearsomely prolific and good — but Walden has been productive and versatile for years, and is now a teacher at her old school, the Center for Cartoon Studies, so she's a veteran. And it does seem a bit foolish to keep marveling at how very much she has done in a short time. I'm still guilty of doing that, of course! What interests me now is the way she is departing from indy-comics expectations, branching out into different kinds of work. Since her last creator-owned graphic novel, Are You Listening? (2019), she has collected many of her early short works, co-created (with Emma Hunsinger) a collaborative picture book, undertaken a work-for-hire Walking Dead franchise series called Clementine, and now this, another collaborative work. Clementine is a trilogy in progress (the second volume is expected this fall), and Junior High promises to be the first half of a duology, so it looks as if Walden is dividing her work between different serial projects over a fairly long span. Huh. I would not have predicted these things a few years ago, but what do I know? Junior High is, we're told, a "lightly fictionalized" riff on the true story of Tegan and Sara Quin's first year in middle school, which in reality happened in 1991 but here is depicted in the present day, with all the cultural differences that that updating entails. For instance, cell phone use is near-constant here, and word balloons that represent texting are an important storytelling device. At one point (45), Taylor Swift fandom comes up in a conversation, but Swift was born when Tegan and Sara were nine! The Quins are upfront about the fact that the Tegan and Sara depicted here are "fictional" (an afterword explains some of the changes they made to their story). In essence, Junior High conveys the gist of junior-high experience circa 1991 in terms easily relatable to readers of that age in 2023. It's an interesting, if perhaps opportunistic, strategy. What matters is that the Quins write themselves and their schoolmates well, and Walden responds with graceful cartooning and beautiful pages. Briefly, the story follows the formerly inseparable twins into junior high, where their different desires and anxieties pull them apart, until their mutual discovery of music (via their stepdad's guitar, surreptitiously borrowed) brings them back together as a singing and songwriting team. Tegan and Sara are indeed hard to tell apart at a glance, and this becomes a running gag (even they sometimes confuse themselves with each other!). The two are pulled this way and that by budding social and romantic longings, with Sara crushing on one classmate, Roshini, and Tegan trying to win the approval of another, Noa, despite Noa's friendship with a bully who makes everyone feel lousy. Different forms of queer longing are gently explored, and milestones of puberty, such as the onset of periods and shopping for bras, complicate the social pressures the twins already feel. Much of the book concerns social maneuvering, the challenges of shuttling between different peer groups, the betrayal of confidences, and the awakening of desire. The writing is confident, the characterization observant and sensitive. What I love about Junior High is the delicacy that Walden brings to the story through her designs and drawing. The book is distinct from her earlier work, dispensing with framed panels and neat borders in favor of a more open, fluid aesthetic. The panels are separated by, not borderlines, but the deft use of negative space and patches of shading and color. This takes a little getting used to — the pages are still dense and busy — but only a little. Most of the story is colored only in shades of purple, recalling Walden's Spinning, but brief interludes — interchapters or pauses that punctuate the story — depict Tegan in blue and Sara in red, and drop the usual density of detail in favor of open layouts full of uncluttered white. These intervals allow the two sisters to reflect and unload in a symbolic space, underscoring their complex feelings. After Tegan and Sara discover songwriting together, Walden adds a vivid gold to the book's palette, bringing out the joys of music. I can't help but contrast Junior High with Walden's current project, Clementine, a survival horror series toned entirely in greys (by Cliff Rathburn of Walking Dead fame). The pages of Clementine, Book One, consist of tightly packed, sharply bordered panels, with layouts that grow increasingly jagged and dynamic as the story builds, leading to some manga-esque diagonals. The work is fittingly claustrophobic, combining Walden's familiar paneling with thick, atmospheric greyscales that match the story's muted horror, laconic storytelling, and emotionally stunned characters. With Junior High, Walden seems to be exercising different muscles, almost reinventing herself artistically. It's interesting to think about these two very different projects being on the boards at nearly the same time (especially coming after such disparate projects as Are You Listening? and My Parents Won't Stop Talking!, her collaboration with Hunsinger). I note that Junior High was drawn in pencil on watercolor paper, then colored digitally in Procreate, whereas Clementine was penciled in Procreate, then printed out and inked in pen on cardstock, so it appears that Walden is deliberately tacking back and forth between different methods. The penciled shading in Junior High opens up something new in Walden's art — and, as ever, I'm amazed at her hunger for growth and experimentation. In all, Junior High is a quiet joy: a smart, meticulously crafted adaptation, and another fascinating step for a wonderful cartoonist.

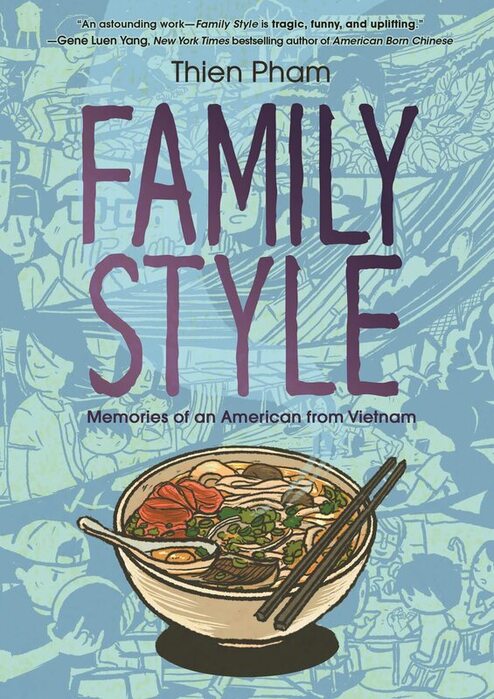

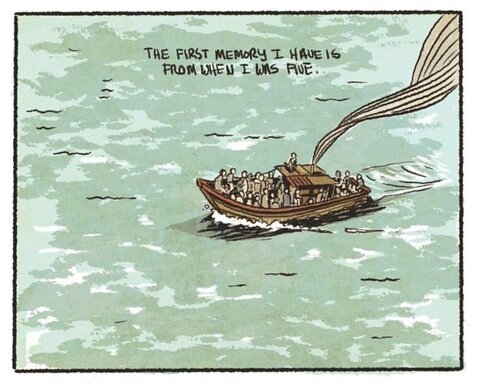

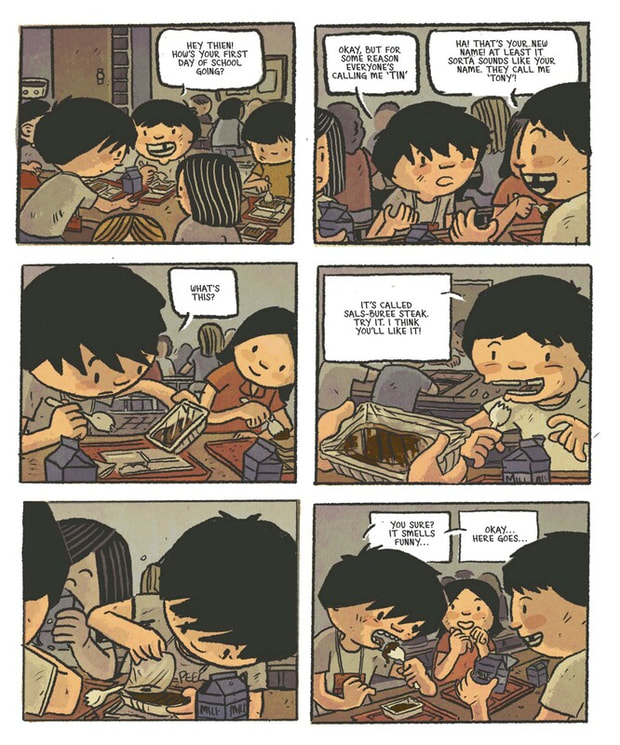

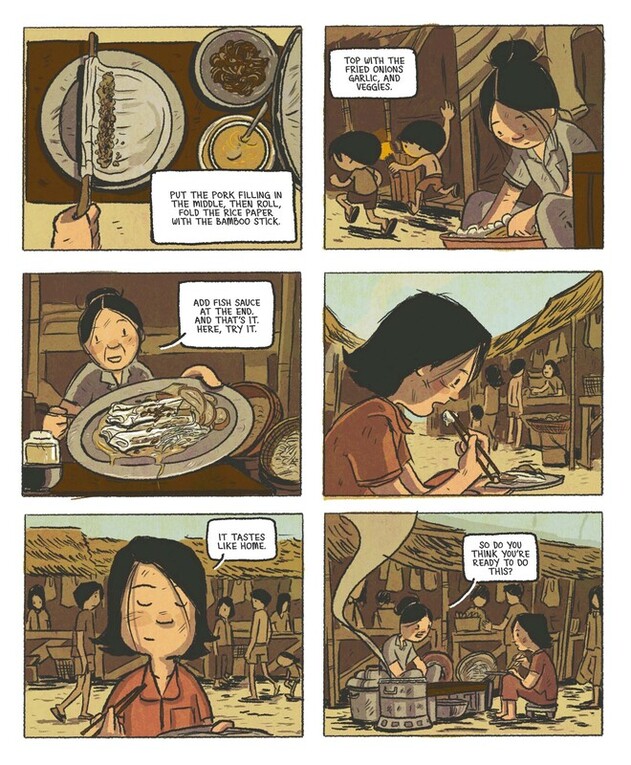

Family Style: Memories of an American from Vietnam. By Thien Pham. First Second, ISBN 978-1250809728, 2023. US$17.99. 240 pages, softcover. Family Style is a fast-moving, elliptical memoir that follows author Thien Pham from about age five to his early forties, starting with his family's emigration from Vietnam circa 1980 as refugees fleeing by sea, and ending with him as a high school teacher in the Bay Area circa 2016, around the end of the Obama presidency — the moment Thien belatedly becomes a US citizen. Through eight chapters, each running roughly twenty to forty pages, Pham follows his and his family's acculturation to the US. Every chapter is titled for a memorable meal, from rice and fish to bánh cuốn and so on, as befits Pham's reputation as a foodie cartoonist/columnist. Each captures a brief snapshot, a moment in time. The early chapters seem to form a smooth continuity, one flowing into the next without pause, but later chapters skip forward abruptly: for example, Chapter 6 depicts him as an elementary student in the mid 1980s, Chapter 7 has him as an adolescent in the late 80s, and Chapter 8 leaps forward roughly twenty-five years. Pham presents the story sans narration, so there is no knowing voice to guide us; we have to pay attention to understand how much time is passing and how Thien is changing. Chapter 5 shows young Thien learning some of his first English words, while Chapter 6 suggests that he has already begun to lose fluency in Vietnamese; Chapter 7 shows him consciously struggling with his in-between status as a somewhat assimilated American teen who is "kinda scared to hang out with other Vietnamese kids" (176). There's an awful lot going on, if you read closely. Pham's fast-moving story is aided by a measured and understated aesthetic that takes everything in stride. Originally published serially to Instagram, Family Style is a blinking narrative, a series of flashes knit together by a steady layout. The pages consist mostly of regular six-panel (3x2) grids, punctuated by occasional single-panel splash pages that bleed out to the book's edge. Pham renders everything in a roughhewn style, with drastically schematized cartoon faces. His digital drawings (created with Procreate on an iPad) are strikingly organic, flecked and a bit scratchy and colored with a muted palette in which colors and tones have a grain and rawness that seems positively earthy. It looks terrific and reads even better. As in the best cartooning, Pham attains a seeming simplicity through complex means — again, if you look closely, there's a lot happening. Some of the most telling details are faraway or half-buried in the mix, waiting to be discovered and puzzled over. Though Family Style begins with harrowing suggestions of violence (only half-glimpsed through a child's eyes), it is really an optimistic, affirming book. Pham is remarkably gracious and funny even as he tells of losses and little betrayals. The story implies the pressure to assimilate and captures Thien's adolescent uneasiness as a cultural outsider or recent arrival, and many little incidents in the book seem sad (for instance, Thien throwing away homemade bánh cuốn so that he can eat Dairy Queen burgers with his mostly White buddies). In this sense, the book is terribly open and revealing. Yet Family Style is quite positive about Pham's process of becoming an American, including the hurdles to citizenship (so, the book's subtitle seems deliberate). Also, Pham's "endnotes," in the form of charming strips about sources and creative process, comically depict him interacting with his parents, who come across as amused informants — lending the book's conclusion a cheerful, settled tone. Even Pham's depictions of privation, as in Chapter 2's patient recreation of life in a Thai refugee camp, are shot through with happy recollections of minor details: a children's game, a small, ingenious life hack, or his mother's unflagging resourcefulness. I'm considering teaching Family Style this fall alongside Thi Bui's celebrated The Best We Could Do, another graphic memoir of Vietnamese American experience (and one I've taught a lot). My reasoning has less to do with commonalities than with differences. In fact, the two books are strikingly unalike. Whereas Bui builds her story alinearly and recursively, moving fluidly from present to past, Pham works in something closer to a straight line. Whereas Bui narrates reflectively, Pham simply shows. Bui excavates family history and recounts Vietnam's decolonization, while Pham concentrates on what he would have seen firsthand. Pham's book is much shorter, and uses a regular layout and blocky cartoon aesthetic in contrast to Bui's dynamic pages and fluid brush inking. Finally, The Best We Could Do is melancholy, introspective, and ambivalent, but Family Style is comparatively high-spirited, even playful (though it hints powerfully at loss and dislocation along the way). What the two have in common is that they are simply great comics. Pham has said that he'd like to follow Family Style with a story about traveling back to Vietnam and recovering family history there. I would happily read that.

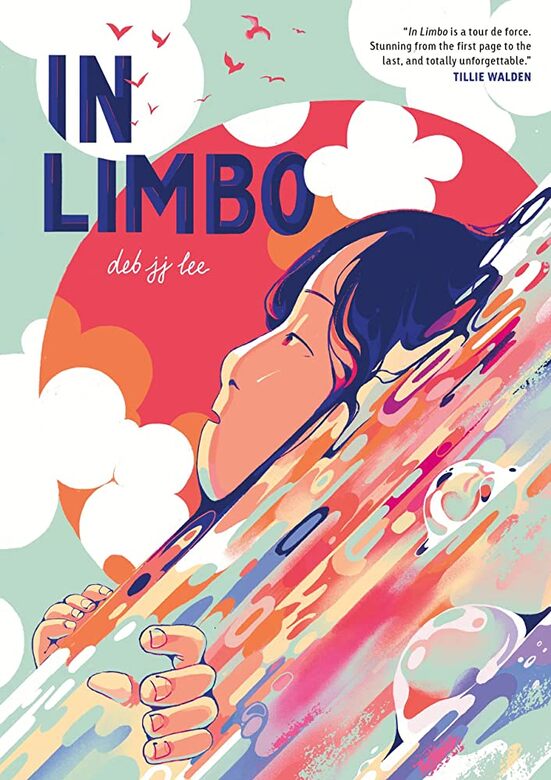

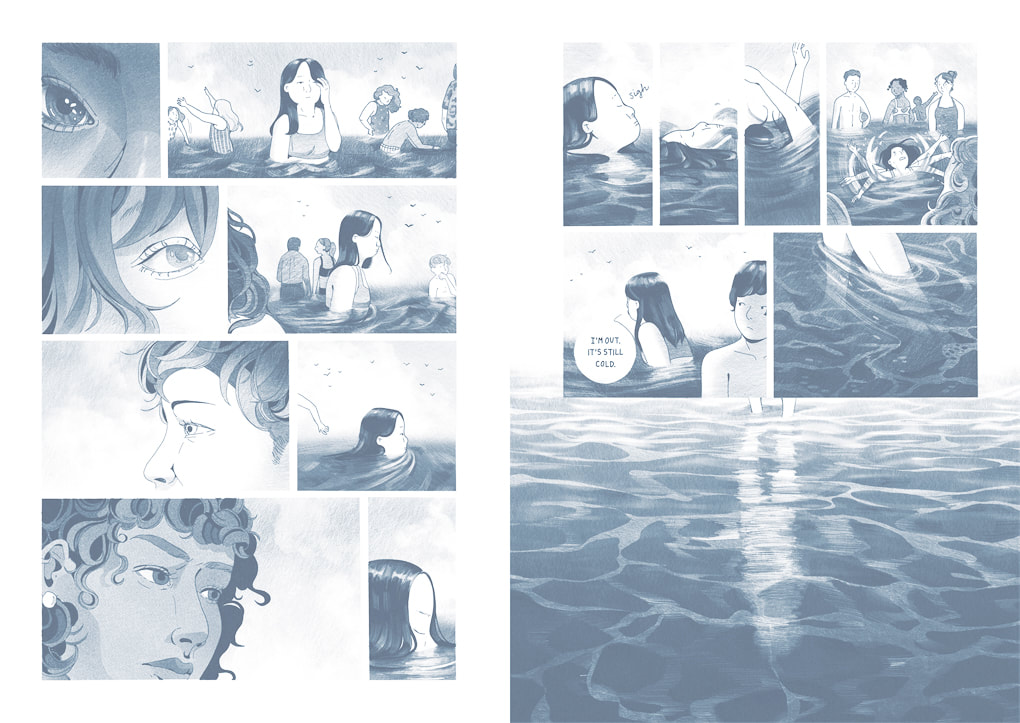

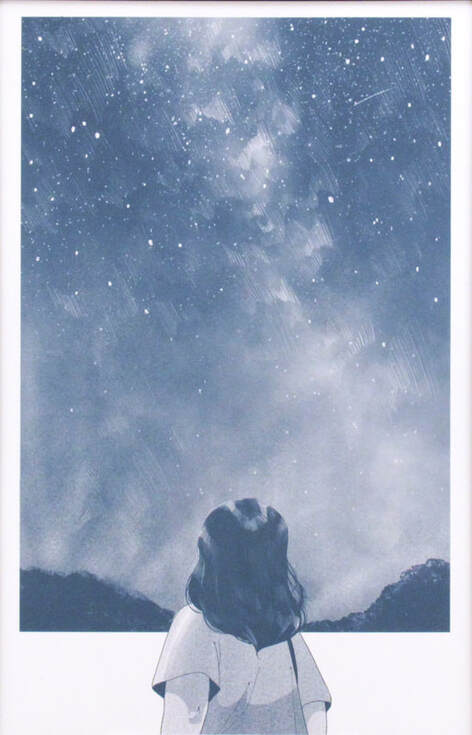

In Limbo. By Deb JJ Lee. First Second, ISBN 978-1250252661, 2023. US$17.99. 352 pages, softcover. I lost sleep over In Limbo. Foolishly, I started to read it late one night, when I was in a sticky, sort of unhappy mood that had nothing to do with the book and much to do with work. I needed to read something that was utterly different than the work I was obsessing over; I needed a way out of my spiraling. So, I thought I would start In Limbo before bed. Just start it, you know? Get my feet wet. But no — once I started, I had to finish. Damn. There was something quietly harrowing about the book, something that frustrated and gnawed at me. I think maybe I was angry with the book's protagonist, and her mother? Or maybe bothered by the evocations of racism, bullying, or depression? Struck by the contrast between the book's elegant, quiet style and its dark undertow? Whatever it was that got to me, I felt pretty helpless about it. I mean, I did put the book down for a few minutes, about a third of the way in, but then I grabbed it up again, anxiously, and plowed on. As the story got deeper and darker, I was all in. When I finished, it was well after midnight — and of course I had the story on my mind as I tried to get some shuteye. Again, damn. In Limbo is a graceful and refined graphic book, a beautiful feat of design, and a moody, enveloping story. It's also observant and brave. Thematically, the book treads some familiar ground: a high school memoir; a Korean immigrant's story; an exploration of familial tensions, crushed friendships, cultural in-betweenness, mental and emotional fragility, suicidal thoughts. The protagonist is a version of author Deb JJ Lee, and the story tracks her four years of high school, leading up to graduation and college after a long spell of desperation and loneliness. Okay, none of that feels unprecedented. But In Limbo is bothersome and riveting, a tough, involving work. I couldn't read it complacently. It pulled me in with its long silences, layered, emotionally telling details, fraught conversations, and occasional shocks. Its cloudy, blue-grey palette, monochrome yet somehow endlessly varied, feels soft, yet Lee uses it to create sharp, crisply defined pages — despite their refusal of black frame lines and their frequent use of bleeds. (Note that in life the author goes by they, but the book genders Deb as she, which, Lee says, more accurately reflects who they thought they were in high school.) Their layouts are often dense and maximally detailed, yet the overall impression is dreamlike, entranced. At first blush, it looks like a book that should be calm. But calm is not what the book is about, and reading it often hurts. What I'm trying to say is, this is a great and hard book. Briefly, In Limbo follows Deborah (Jung-Jin), or Deb, through her four years of high school as she tries to love and understand herself, embrace art as her vocation, and get out from under her family's expectations, especially the relentless needling of her very driven, at times abusive, mother. Her mom, as a character, hews perilously close to the "tiger mom" stereotype (as the book itself acknowledges). Their relationship is full of jagged edges and cruel scenes — and it's one of the things, I think, that caused me to read on, after midnight, in hopes of relief or understanding. Deb's father and brother don't register as strongly; In Limbo is very much a daughter/mother story. Yet it's also about friendships, sometimes fraught, overburdened ones. Deb's feelings for her friend Quinn, to whom she has a sort of desperate, proprietary attachment, lead to surprising reversals. Officially, In Limbo is described as "a cross section of the Korean-American diaspora and mental health," and that seems right, but it is Lee's depiction of complicated, ambivalent relationships that yields the greatest shocks. Lee doesn't show young Deborah as a good friend; instead, they show her taking friends for granted, or reading them strictly through the lens of her own anxiety, or laying terrible responsibilities on them. In this sense, the book seems self-accusatory. Deb doesn't understand what she's doing, of course, and the story is partly about her coming to grips with how she hurts both her friends and herself. Some relationships outlive the end of the book, others don't, but the book is remarkably generous in the home stretch, as Deb opens out from the tortured inwardness of the first half and learns to see more clearly. To say that the book's characterizations are complex would be a measly understatement. In Limbo doesn't resolve every problem it raises. This is probably partly by design; Lee has acknowledged in interviews (again, see this one) that their life, past and present, is more complex than a single book can cover, and the book seems anxious to show Deborah as a work always in progress. There are things in the book I'd have liked to know more about. Some relationships and threads are still nagging me, even now. Some readers may finish the book wanting to know more about Lee's understanding of internalized racism and the pressure to assimilate. Some may wonder about the connection between those things and the book's tormented mother/daughter dyad (cf. Robin Ha's graphic memoir Almost American Girl). Some readers may be anxious to know more about the mother's abuse, what prompts it, and how Deb lives with it (cf. Lee's own short comic from 2019, "Dear CPS," readable on their website). Some may wish that the Künstlerroman aspect of the book came through more strongly, that they were left knowing more about Deb's artistic vocation. Some may wonder about Deb's implicit queerness or perhaps about gender nonconformity. I've been thinking about all those questions; the book feels a bit tentative about what to include, what to leave out, and how to balance things. That said, I don't expect complete "closure" in memoir, and when I do get it, I worry that I'm being sold a bill of goods. In Limbo has honesty and emotional rawness despite its delicately finished surface, and I dig that. That "surface" is going to draw in and mesmerize a lot of readers, I expect. The book's rapturous reception has a lot to do with Lee's virtuosity as an illustrator and designer (indeed, the many blurbs on the cover note their lush, meticulous art). In Limbo is visually extraordinary; the book is gorgeous and transporting, a master class in narrative drawing and sustained mood. That mood is melancholy almost the whole way through, but In Limbo is vital and ravishing enough to make one fall in love with melancholy. (My images here don't do the book justice.) I'm grateful to this book for introducing me to a singular and gutsy artist. Most highly recommended: another high watermark for autobiographical comics about adolescence. <3

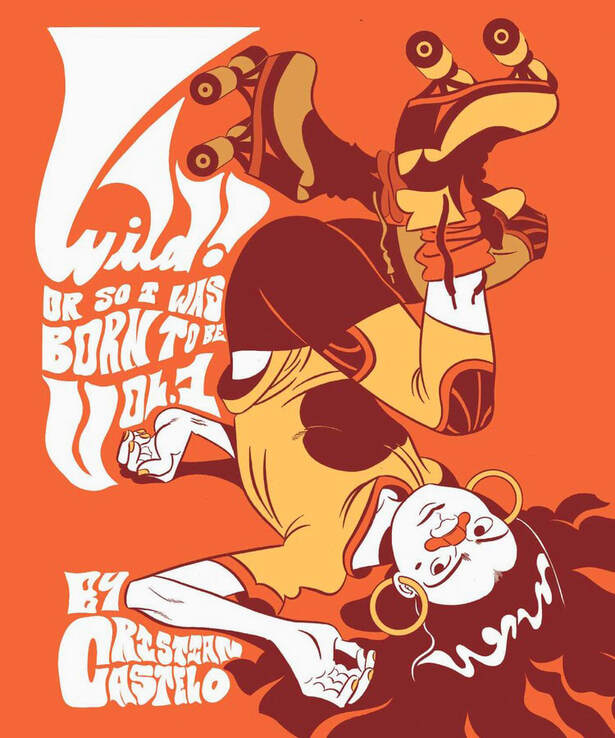

Wild! Or So I Was Born to Be, Vol. 1. By Cristian Castelo. Oni Press, ISBN 978-1637150931, 2022. US$29.99. 208 pages, oversized softcover. Wild is a delightful yet frustrating comic. Delightful because artist Cristian Castelo cartoons the hell out of it, with an energetic, superflat, ultrabright style. The pages sing. The story's 1970s roller derby milieu and fearsome all-girl cast (reminding me a bit of Jaime Hernandez's wonderful luchadores) grant him license to do colorful, braggadocious roller rink action and cartoon violence. It's a gas, full of fierce posing, trash talk, and big, mythic characters. The sizzling red/orange/gold palette, outsized format, and inventive layouts practically gave me a contact high! So, yeah, I enjoy rereading and poring over this comic. OTOH, Wild is confusing as hell. Beyond protagonist Wild Rodriguez and a couple of hard-bitten, superheroic roller divas, the cast is indistinct. Supporting characters blur into each other, and everybody lurches off-model. In fact, some characters don't seem to have a consistent model (in one scene, a very minor bit player ends up looking like four different people). The settings lack a 3D sense of habitable space, and action does not flow logically from panel to panel. Locales are gestural at best, and the high-throttle action scenes don't actually communicate anything about roller derby as a game. There is snarling and there is hitting, but what else is the sport about? The plot lunges here, then there; eccentric narrative doglegs turn out to be crucial (the accumulated effects of serialization are all too easy to see). Cross-cutting between different locales and different bouts makes the book's home stretch dizzying, and not in a good way. Castelo's elastic cartooning works somewhat against narrative coherence. His style has shifted a lot since this project began. In 2019, I bought one of the riso-printed, handbound collections of the unfinished Wild (then a work in progress) at comicartsla.com, and I can see remnants of that draft here, in panels that are not quite as crisp as the rest of the book. The newer style is razor-sharp and fairly staggering. At times, Castelo seems to have worked over (and around) the older stuff, punching it up, adding new connections, rethinking and complicating the story — but the end results don't add up narratively. Problems in simple legibility are made the worse by Castelo's expressionistic, ever-shifting use of his limited color palette; the characters' costumes are not taggable by color, because a yellow outfit in one panel becomes a red outfit in another. That may sound like a petty complaint, but it becomes a problem due to the sheer density of the pages, indistinctness of minor characters, and ill-advised cross-cutting between scenes. The book is just plain hard to follow. But man, what cool things are hiding in here: Wild Rodriguez's mixed family and ambivalent ethnic identity; the roller divas' complicated, nuanced backstories; the way the major characters bear the weight of cultural politics; the sheer unabashed ass-kicking comic fury of the story. One aspect that makes the reading even harder — the difficulty of parsing "dream" from "reality" — strongly appealed to me. So did the overwhelming style. I'm glad to see such a vaulting, ambitious, and, yes, wild comic touted as a YA book. Castelo may yet deliver a great all-around comic. I bet he will. In any case, I'll happily queue up for the next volume of Wild. My complaints notwithstanding, Volume One is a gorgeous, headstrong, gutsy experiment. I think it fails narratively, but it fails in such a way that I long to see what Castelo does next.

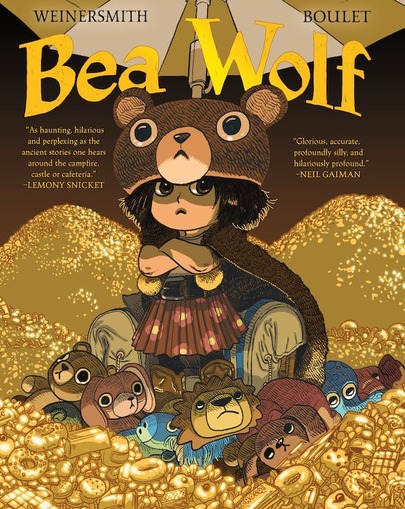

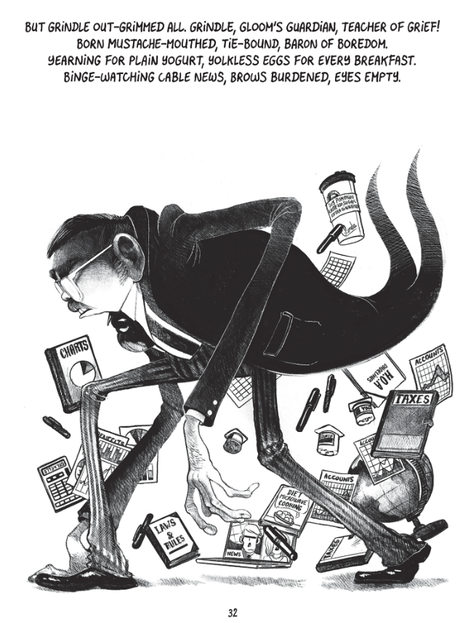

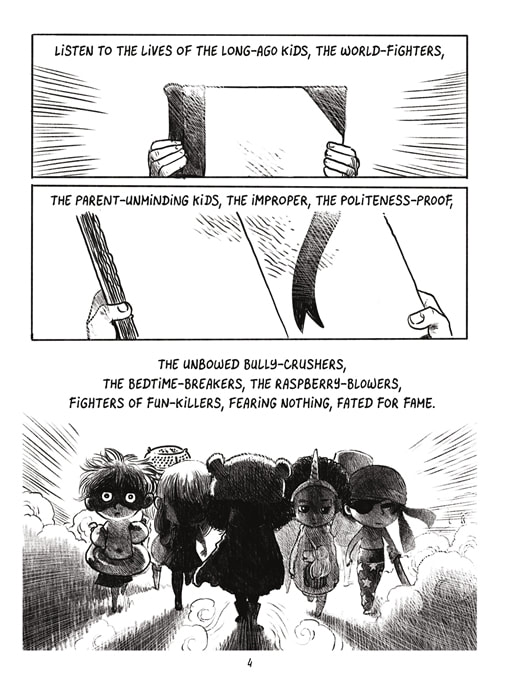

Bea Wolf. Written by Zach Weinersmith. Art by Boulet. First Second, ISBN 9781250776297, 2023. US$19.99. 256 pages, hardcover. Bea Wolf is brought to you by the same team that did the illustrated book Augie and the Green Knight some years back: Zach Weinersmith and Boulet. It's a graphically sumptuous retelling of Beowulf as a battle between rowdy, joyous kids and tedious, joy-sapping adults. Its proper soundtrack would be the number, "I Won't Grow Up," from the 1954 musical Peter Pan. That is, Bea Wolf assumes a world where kiddom is matter of keeping adulthood at bay. This raises the question of whether kids really want to continue being kids forever (a common fantasy among adults) or whether they want to, you know, gain more agency and autonomy in their lives. Bea Wolf has its cake and gobbles it too, depicting kids who have plenty of agency, of a fierce, ass-kicking kind, yet remain very much kids: big-eyed, neotenic, button-cute, and round. They're ruthless in claiming a certain kind of childhood: the kind that is all about performing irresponsibility, about waywardness, wildness, messiness, junk food binges, rude joke-telling, and wearing your underwear on your head. Their Grendel is "Mr. Grindle," a neighborhood Gradgrind who specializes in cleaning up, sanitizing, and disciplining, and in aging children with his deadly, withering touch. Of course, the kids have to fight him. Bea Wolf, then, is a celebration of childhood's anarchic side, even though, oddly, it features a kid "kingdom" with rulers and dynasties and national heroes. The "monster," in this case, is adulthood, and heroism consists of resisting it. There's a touch of Roald Dahl in all of this, and of course Peter Pan, and quite a bit else besides: familiar stuff. So, Bea Wolf is an elaborate, prolonged joke. Really, it's a bit of a soufflé, the sort of thing that needs to stay light and airy if it's going to work at all. Heaviness, ponderousness, would be deadly. The thing is, spoofing Beowulf usually does involve some heavy lifting. The language is technical and hard to ape; the world evoked is remote and strange. This is esoteric stuff by current children's book standards. Happily, Bea Wolf finds smart 21st-century analogs for the poem's beasts and heroes, and stays light enough to elicit chuckles from start to finish. I even laughed aloud at several points, early and late, which is unusual for me when reading a long comic. Part of what makes this work — for me, it may be the biggest part — is that Weinersmith is very good at parodying the "voice" of Beowulf: the rugged prosody, loping parataxis, alliterative phrasing, and vivid kennings of the old Old English. I mean, he does this hilariously well, from the start: The book has a firm voice, full of flavor, that stays the course despite the odd moment of deflation or comic anachronism (e.g., "Dawn rose, like a jerk"). Sometimes the verse rises to truly affecting poetry, like Bea's great last line on this page: Another thing that makes all this work — and I confess, this is what drew me to the book in the first place — is the cartooning of Boulet (Gilles Roussel). Boulet draws up a storm, makes the risible setting believable (enough), and transforms cliched, doll-like children into ferocious heroes. His digital renderings (drawn on iPad via Procreate) mimic the look of pencil and charcoal and brush, with, at times, a texturing so dense as to recall scratchboard — yet somehow he manages to maintain the necessary lightness and energy. Every spread is different, and many are quite elaborate. Layouts are dynamic, grids are avoided, and frame lines are using sparingly, so that each page-turn brings up another compositional treat. Man, he's good. In all, Bea Wolf is a charming book that may appeal most to lit nerd adults and the children who share their pleasures. Reading it feels a bit like playing an adult-centered but kid-styled game (Unstable Unicorns, maybe?). I dug it, and, er, I Iive in that kind of household. So, yay!

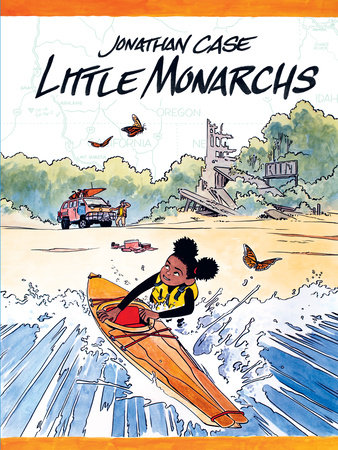

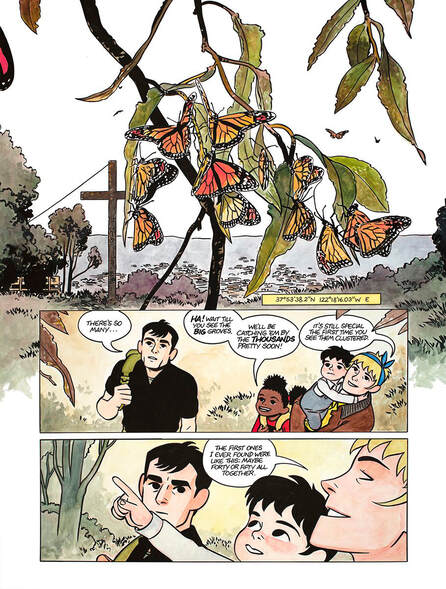

Little Monarchs. By Jonathan Case. Holiday House/Margaret Ferguson Books , ISBN 9780823442607 , 2022. US$22.99. 256 pages. A Junior Library Guild Gold Standard Selection. This post comes belatedly and is not much more than a mash note. A few days ago, I called the Eisner Award-nominated Little Monarchs, by Jonathan Case, "an extraordinary piece of worldmaking, ... dense, involving, subtle, and beautiful." I stand by that. It is one of the best graphic books for readers of any age I've read in a while (and I've been reading a lot of good ones lately, now that school is out). I dove into Little Monarchs hurriedly, without doing my usual obsessive reading of paratexts, indicia, and so on (I'm usually a bit compulsive about how I crack open books that are new to me). I had the book out from my local branch of LAPL and was bingeing before casting my annual Eisner votes, so I was rushing. I hadn't even read the jacket copy. So, it wasn't until I finished the first of the book's dozen chapters that I began to realize that the story was set in a world I did not quite recognize, or a changed version of our world where something had gone wrong (I overlooked a detail given on the first page: that the date is 2101). In fact, Little Monarchs is a post-apocalyptic survival story, though officially a middle-grade (ages 8-12) sort of book. In it, a ten-year-old girl, Elvie, and her guardian, a forty-something biologist named Flora, drive through a drastically depopulated North America in which most people dwell underground, unable to travel safely in sunlight. Elvie and Flora mostly avoid encounters with these "deepers," preferring to go it alone. They dread attacks by "marauders," that is, scavengers who would pirate their stuff.  So, the world of Little Monarchs is different. In it, about fifty years have passed since a "sun shift" has killed off most mammal life. Prolonged exposure to direct sunlight (more than a few minutes) can be fatal. Most human survivors are socked away in underground bunkers, and only a few crepuscular or nocturnal mammals, such as bats, can hope to survive. Flora and Elvie are able to live topside because Flora has developed a medicine that keeps them safe from "sun sickness" for up to about a day and a half at a time. The medicine derives from the milkweed within monarch butterflies, so Flora and Elvie follow the yearly path of the monarchs' migration, catching butterflies, harvesting scales from their wings, releasing them, and creating ever more batches of meds. At the same time, Flora seeks a more permanent solution in the form of a heritable vaccine. Little Monarchs, then, is the story of an never-ending road trip and a scientific quest. Remarkably, this survival story reads less like horror and more like an adventure. That has everything to do with the character of Elvie, a Black girl who is resourceful, eagle-eyed, courageous, decent, and funny. Elvie explores and improvises and above all uses her head. She can face down her fears and make do when disaster strikes. The heart of Little Monsters is the bond between Elvie and Flora, her White caregiver, who is something like a mom, big sister, tutor, and friend all at once, and whose quirks Elvie knows and forgives. You can believe that these two understand and love each other. The book gains heft from Elvie's journal entries: expository interludes that serve to orient the reader while showing off her smarts. These entries combine Elvie's home-school assignments (given by Flora), drawings, reflections, and tips. Elvie knows how to live in the wild world Jonathan Case has imagined, and her entries impart a great deal of knowledge. Case has mapped her story onto real locations, using real geographic coordinates, and included a wealth of fascinating detail about everything from knot tying to the monarchs' life cycle. The story-world fits this girl to a tee, and vice versa. Little Monarchs takes interesting risks. As a survivalist story in a broken world, it delves into the hard ethical questions that such scenarios tend to pose: What are you willing to do to survive? Do the ethical constraints of civil society apply when the world has been upended? Must you be willing to hurt others to protect yourself? The story kicks into gear when Elvie finds another, much younger child wandering in the sunlight and has to take him in, which leads to Elvie and Flora nervously weighing the risks of involvement with other people. At first, Flora seems somewhat mistrustful, even phobic, about taking that risk, but, as things turn out, she has good reason to be. There are reversals, betrayals, and shocks in the story. The last act depicts hard things — and Elvie has to do some hard things, too. Little Monarchs isn't The Road, of course (RIP to the brilliant Cormac McCarthy), but does ask its readers to weigh questions of ethics and risk in the face of grave danger. Somehow it does this and remains a thrilling adventure and credible middle-grade story about a plucky ten-year-old kid. And the visual artistry of it! Little Monarchs is a feast of lovely images made by hand, from the lettering to the gorgeous watercolors. Reading it against a backdrop of other recent graphic novels for young readers, even good ones, I was reminded of how seldom I get to see work at this scale that is handcrafted even down to its finest details. Case is a terrific comics artist, designing dynamic pages, drawing believable characters and environments, pacing and punctuating riveting sequences of high-stakes action as well as quiet scenes of discovery, and making every detail count. As I said a few days ago, he cartoons with an economy and grace that recall Alex Toth as well as latter-day classicists who have drunk from the same well: Jaime Hernandez, R. Kikuo Johnson, and Chris Samnee. His character designs, breakdowns, staging, and layouts are equal to his terrific writing. Little Monarchs urges engagement with the natural world and offers readers all sorts of potential adventures off the page as well as on. You could take this book on the road with you and learn a lot. More than anything, it is a classic quest story, pulled off with warmth, wit, and bravery, surprising and gutsy right up to its very last page. After reading so many well-intended moral and political fables for children in which messages are reliably delivered and conclusions are just what one would expect, I took delight in its splendid eccentricity. Highest recommendation!

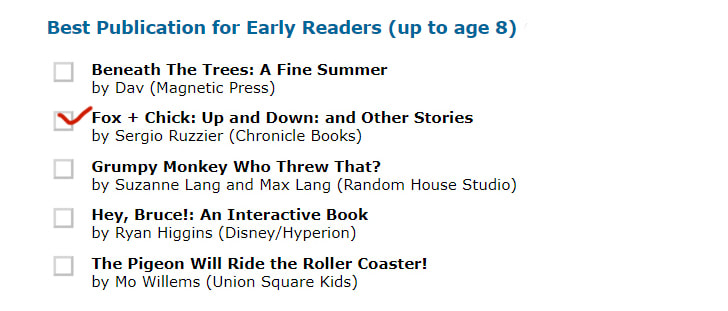

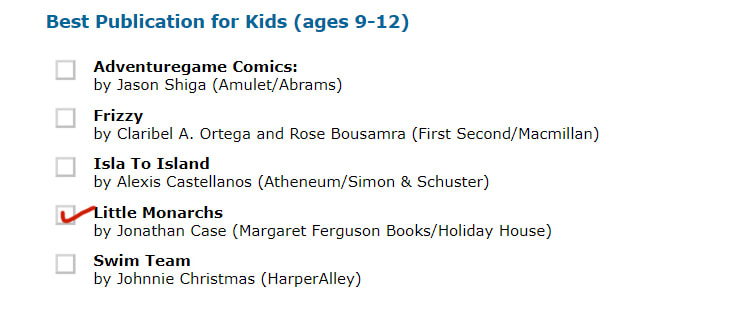

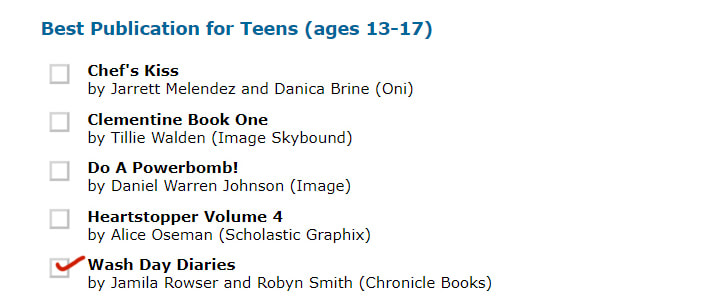

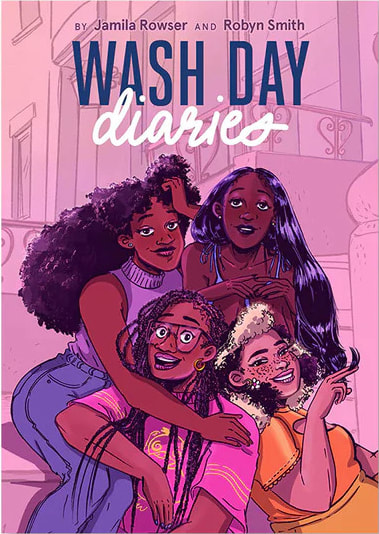

I like to keep up with the Eisner Awards. I'm a former judge, I value recognitions of excellence in the comics world (even when they're contentious), and I like staying in touch with the process. Honestly, it can be hard to find and read every single nominee, but each year I pay particular attention to, and try to spend time with, all the nominees in the young readers' categories. Currently, that means three categories: Early Readers, Kids (ages 9-12), and Teens. Over the past week, I've read about ten books to get up to speed! I'm told that today, June 9, is the last day to cast votes (officially, the vote is "open until June 10, 2023 12:01 AM (GMT-05:00) Eastern Time"). So, this evening I'm going to vote in as many categories as I feel qualified to vote in! This year's Eisner process has been especially vexed and controversial (leading to a retroactive withdrawal from the ballot). The ballot has been a bit mystifying to me, with some, IMO, startling omissions and puzzling categorizations. But controversy is in the nature of the awards, and I still appreciate the heuristic value of this, let's say, yearly exercise. Here are my thoughts on the Early Reader, Kids, and Teens categories:  Early Readers: I admit, this is not a category that interests me much this year. There are some lovely images here (for sheer sumptuousness, Dav's Disneyesque watercolors are hard to beat), and some nice comic bits (the page-turns of Higgins, the pacing of Willems), but for the most part these books strike me as pat and aesthetically undaring. There's a lot of shtick here, which tires me out. I miss seeing some good TOON Books in this category; 2022 seems to have been fallow for them. That said, my choice here is this charming, quietly ironic, aesthetically delicate take on friendship and learning:  Kids (9-12): This is a more interesting category by far, in fact one of the deepest in this year's ballot. The craft on display is impressive (dig the cartooning in Frizzy and Swim Team), and the ambition (dig the near-wordless storytelling of Isla to Island, a complex tale of immigration, loss, and discovery; or the interactive, formally ingenious Adventuregame). But my hands-down choice is Little Monarchs, an extraordinary piece of worldmaking, which is cartooned with an Alex Toth-like economy that reminds me of elegant classicists like Jaime Hernandez, R. Kikuo Johnson, and Chris Samnee. An amazing book, so dense, involving, subtle, and beautiful: Teens: It's nice to see Tillie Walden in this category, for a book that is a change of pace for her. But I think the outstanding title here is the already much-talked about, groundbreaking Wash Day Diaries, a suite of stories about four Black women and the strength of their friendship and interconnection. Every character in this book has a backstory, but Rowser and Smith smartly leave us guessing, focusing on the energy, grace, and good humor of the four. Darkness marks the edges of the story, but joy wins out. The book seems casual, the way eavesdropping on good friends can, but that's deceptive; there's a lot going on. The chapter devoted to their "group chat" is a wonder of form as well as characterization. I admit that I didn't see this as a YA book at first, but then, I usually have that reaction to books that turn out to be very good YA books! A few observations:

This summer, for the first time, I'm teaching a course for UCLA's California Rare Book School (CalRBS). Titled "The Social and Material Lives of Comic Art, or, How Comics Get Around," the course is part of a new partnership between CalRBS and the Smithsonian Libraries and Archives in Washington, D.C. I'm thrilled to be doing this! As I envision it, the course will be a hands-on workshop that will draw upon the Smithsonian, the Library of Congress, and other D.C.-area resources, involve several site visits or field trips, and bring in multiple guest speakers. If you'd like to know more about it, or would like to apply, visit: Popular yet personal, branded as trivial yet rich with meaning, comics are more than cultural scraps or leftovers. In fact, comics are everywhere: they are art objects, storying machines, readable games, tools for disseminating knowledge, and platforms for worldbuilding and political argument. Whether viewed as historical artifacts or distinctive literary and artistic works, comics carry culture with them. In this workshop, we will study how comics move through the world, socially and materially, how they can make a difference in the world, and how we, as teachers, researchers, and creators, can use them. Comic art has a complex social life. Comic books, graphic novels, strips, and cartoons come in varied material (and now digital) forms and reach diverse readerships. Many are thought to be ephemeral, as disposable as yesterday’s newspapers or tweets; some are built to last. Many last despite their seeming ephemerality, archived by collectors, fans, and, increasingly, archiving professionals and research libraries. Conserving, organizing, and accessing these artifacts can be a challenge but also a profound pleasure; comics offer us opportunities for creative engagement as well as deep research. Our workshop will study how comics come to be, how they circulate, where and how they are archived, and how we may teach with them. We will focus on comics’ physical materiality, on firsthand experience and “show and tell.” Our hands-on sessions will mix varied forms of nineteenth, twentieth, and twenty-first century comic art, from newspaper pages to comic magazines, from graphic novels to minicomix, zines, and webcomics. Drawing on the resources of the Smithsonian Libraries and Archives, we will explore the material and social histories of comics, the idiosyncrasies of comics production, including differences among American, European, and Japanese traditions, and how comics have been shored against time by collectors. We will consider comics as products of various industries, cultures, and social scenes—as historic artifacts, yes, but also urgent dispatches from the here and now. Participants will come out of this workshop knowing:

Do visit the CalRBS website, above, to find out more about requirements and credits! Also, please spread the word to anyone you think might be interested!

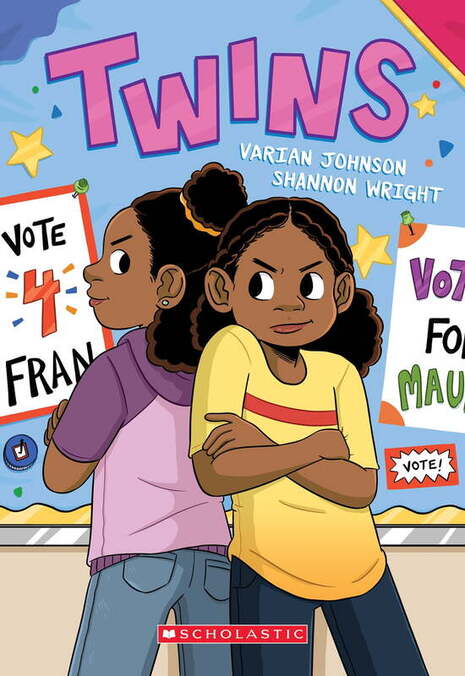

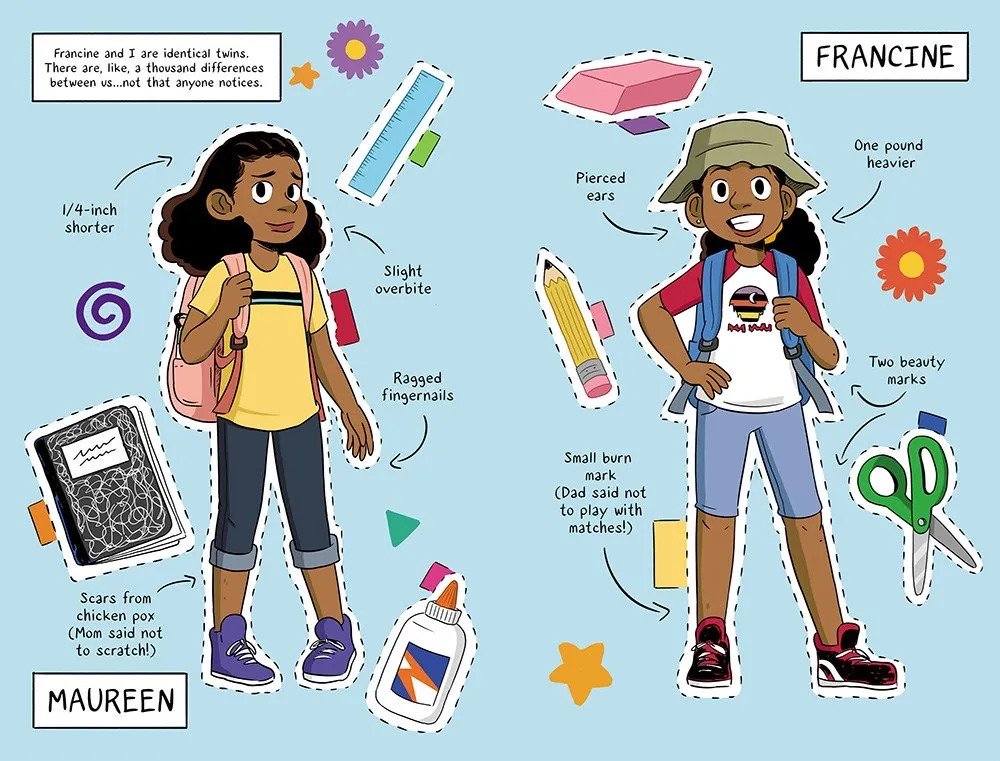

Twins. By Varian Johnson and Shannon Wright. Scholastic/Graphix, ISBN 978-1338236132 (softcover), 2020. US$12.99. 256 pages. Last week I belatedly read Twins, a much-praised middle-grade graphic novel published by Scholastic in 2020 — a first graphic novel for both writer Varian Johnson, who is a prolific novelist, and artist Shannon Wright, who has illustrated a number of picture books (most recently, Holding Her Own: The Exceptional Life of Jackie Ormes). Twins is good, but left me wanting more. The plot concerns identical twin sisters, Maureen and Francine, who have always been close but begin to pull apart as they enter sixth grade. They end up running against each other in a student body election, a rivalry driven by mixed or confused motives that hurts their relationships with friends and family. The book boasts many nicely observed, sometimes poignant, details: novelistic good stuff. The plotting balances the twins' need for individuation against their strong bond, with a sense of earned insight for both sisters. There are astute cartooning choices along the way, including full-bleed splash pages that capture moments of struggle, hurt, and growing realization. Compositionally, Wright delivers, with emotive characters, startling page-turns, and a confident grasp of what's at stake dramatically. Twins, I admit, strikes me as more reassuring than challenging. It's on familiar middle-grade turf, with a story of girls becoming tweens and growing more sensitized to social nuances and strained friendships. There are soooo many graphic novels currently working this turf. The setting is anodyne: a comfortably middle-class suburbia with dedicated students, supportive teachers and families, wise parents, and lessons on offer about self-discipline, self-confidence, and leadership. Loose ends are tied and every arc resolved, or at least reassuringly advanced, by book's end, with no one coming off the worse. Some elements, however, seem under-thought or cliched — for instance an ROTC-like "Cadet Corps" at the school, a plot device that allows for a fierce, drill sergeant-like teacher and moments of tough discipline for the more timid of the two sisters, who of course comes out the stronger (but oh the unexamined militaristic overtones). The book is inclusive and aims to be progressive, focusing on protagonists of color (Maureen, Francine, and their family are Black) while downplaying the usual generic thematizing of racism and classism as "problems" to be suffered through (a tendency expertly spoofed by Jerry Kraft in New Kid). One scene deals with shopping while Black and implies a critique of unspoken racism, but that thread isn't woven through the whole book. That in itself might be refreshing; the book thankfully avoids potted depictions of racialized suffering and trauma. Yet for me there is too little sense of social or institutional critique; the twins' relationship and personal growth are the main things, to the point of presenting adult choices uncritically and tying up the story without any lingering sense of mystery or depths remaining to be plumbed. In a word, it's pat. Perhaps I'm guilty of wanting this middle-grade book to be more YA? That wouldn't be fair, of course. But Twins is one of so many recent graphic novels that, from my POV, appear boxed in by children's book conventions, more specifically by the rush to affirm and reassure. The contours of this kind of book are starting to seem not just clear, but rigid. Young Adult books too have their conventions, one being skepticism of adult choices and institutions, and I don't know if I'm asking for that. Perhaps what I'm wishing for is something else: a touch of mystery, maybe, or a respect for the unfinished business of living. Twins is a traditional tale well told, with all its arcs well finished and its major characters affirmed and advanced. I just can't imagine re-reading it for pleasure. Some readers will stick to the book like glue, I expect. The characterization of the twins is complex, and Maureen, who is the book's focal character and real protagonist, is especially well realized: a socially anxious nerd and academic overachiever but not a shrinking violet, not a cliché. Johnson and Wright know these characters and treat them kindly; their dialogue clicks. Plus, the art is full of smart touches, and Wright offers clear, crisp cartooning and dynamic layouts throughout. Some moments registered very strongly with me: for example, the scene early in the book where Maureen and Francine get separated at school and a page-turn finds Maureen stranded in a teeming crowd of other kids, lost. Yet the book's brightness and formulaic coloring, which favors open space, solid color fields, abstract diagonals, and color spotlights, strike me as simply functional, and in the end more busy than harmonious. While Wright excels at characters, the settings appear textureless and a bit bland. Her page designs are restless, inventive, and clever, the storytelling clear, yet the governing sensibility seems, again, generic to my eyes. It's right in the pocket for post-Raina middle-grade graphic novels, but doesn't grip me. The middle-grade graphic novel is one of the most robust areas in US publishing, and the novel of school, friendship, and social navigation is its nerve center. Twins is a fine example of that. I think I'm becoming more and more jaundiced about that kind of book, though. I can now see the outlines of a formula, and I'm getting jaded. I admit, this realization has me rethinking the bright burst of enthusiasm with which I began Kindercomics five years ago.

|

Archives

June 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed