|

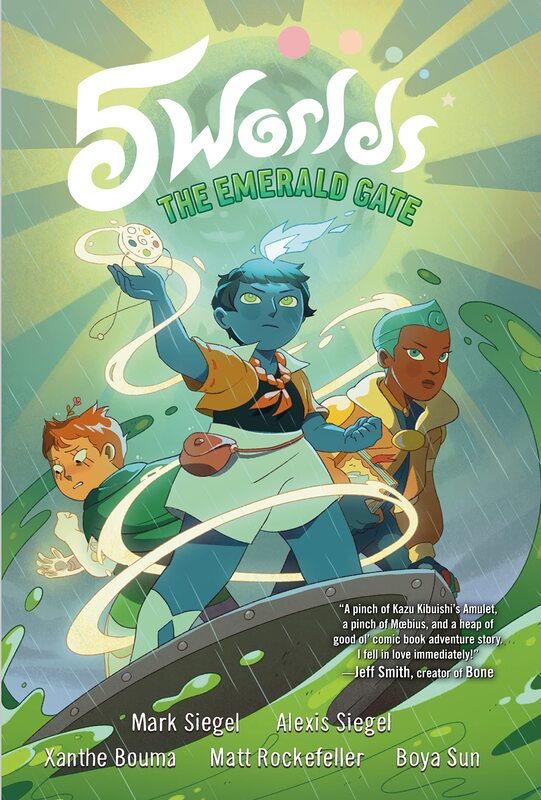

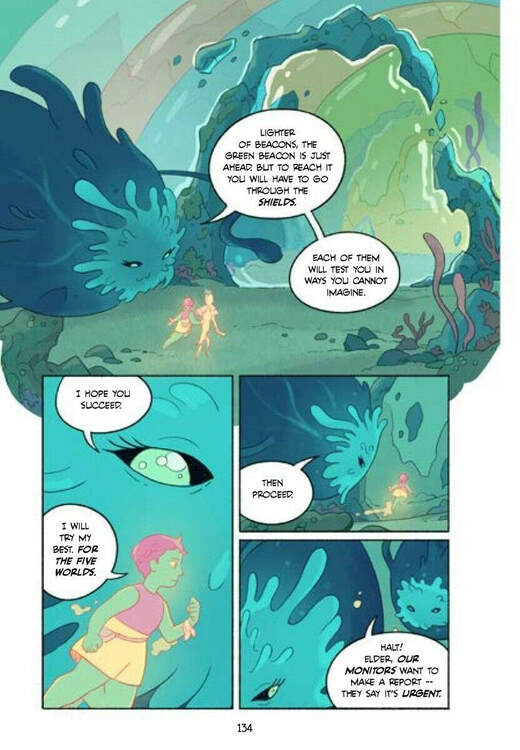

5 Worlds: The Emerald Gate. By Mark Siegel, Alexis Siegel, Xanthe Bouma, Matt Rockefeller, and Boya Sun. RH Graphic/Random House, 2021. The 5 Worlds series (five books set on five planets, published over roughly five years) has always been a high-wire act, balancing space fantasy, ecofiction, and Miyazaki-esque tropes with allegorical broadsides against neoliberalism and right-wing populism—all of this served up by a complex collaborative team consisting of five geographically dispersed co-creators. The way they have all worked together is a bit of a miracle. I’ve reviewed every volume (one, two, three, four) and keenly followed the evolving story of heroes Oona, An Tzu, and Jax and the many co-revolutionaries and loved ones they’ve gathered along the way. The series reaches it big finish with The Emerald Gate, and it’s a corker of a climax. Overall, the series has proved smart, bold, and very good—though I must admit it has left me with a sort of gnawing dissatisfaction, somehow. Pointedly allegorical from end to end, 5 Worlds has targeted egotism, greed, environmental carelessness, demagoguery, and (most clearly in Book 5) gradualism and hidebound deference to tradition, as its youthful heroes throw off the shackles of what has been done in favor of what can be done. The story is unabashedly progressive, topical, and on the nose. The Emerald Gate, dedicated to “the young people not waiting for permission to bring long overdue change to our world,” casts lead heroine Oona as a Greta Thunberg-like climate activist who must defy authority and take big risks to make big changes. The Five Worlds of the title are suffering a gradual ecocide—that is, dying of heat death—but an oily Trumpian oligarch (possessed by an ancient dark force) is trying his damnedest to smother that fact. Only drastic measures can save the day. This final volume’s signature phrase, Green doesn’t wait for permission to grow, signals Oona’s shift from diffidence to absolute certainty; she is done questioning, and now knows the way. Though the book takes time to sow little seeds of doubt (What if Oona’s plan only plays into the villain’s plan? What if the perfect solution turns out to be perfectly disastrous?), there really is no doubt: Oona and her fellow heroes must do something radical, must play for the highest stakes, if they are to save the Five Worlds. They must rebel. Oona must rebel. Above all, she must embody moral and political certitude. The Emerald Gate, more than its four predecessors, reveals an odd tension: between the radically egalitarian and democratic spirit to which the series aspires, and, on the other hand, the near-deification of Oona, the fated heroine who must give her all for the cause. In the home stretch, Oona undergoes a sort of ritual testing, running a gauntlet of five “filters” or “shields,” that is, moral and psychological trials, so that she can recognize “the truth.” Through this ritual, Oona rejects tradition and hierarchy, factionalism and rage, egocentrism, and personal desire. In effect, she rejects the novel’s version of neoliberalism. But this renunciation is the key to her final apotheosis; even as she rejects crude individualism, she is affirmed as The One who can channel the virtues and energies of all Five Worlds. While every member of Oona’s team plays a vital part in the novel’s ending, their final success depends on deferring to Oona’s vision and artistry (“Do not tell me your plan. I trust you”). In this way, the story uneasily mixes the political and the mythic—and remains, perhaps in spite of itself, a heroic fantasy in awe of individual gifts, somewhat at odds with its collectivist ethos. What makes all this work is that there is a price to pay. I won’t get into the details; suffice to say that Oona’s apotheosis entails a change of state and a goodbye—though also a sort of opening into ineffable new possibilities. Her transformations are so dramatic that she cannot return to ordinary life. Nor can she be quite understood. To resolve the story, Oona must escape the containment of the story, must step outside the frame her friends (and we readers) understand. Channeling the powers of the Five Worlds means being more than a person, and so there is lovely sense of consequence to the ending. What I’m talking about is not quite the wounded bittersweetness of Frodo Baggins at the end of The Lord of the Rings, but at least something that surprised me and made me reread the last few pages with care. The Emerald Gate well and truly finishes the story of Oona that began in 2017 with The Sand Dancer. I look forward to rereading this series all at one go. Aesthetically, it’s remarkably cohesive, a seamless collaboration despite the complex interworking it so clearly required. The Emerald Gate is (as I’ve come to expect) a sumptuous feast of worldbuilding and of deft, surehanded cartooning. The payoff in the end is rousing and full of feeling, enough to knock me for a loop. Overall, the book comes across as a paean to the indomitable spirit and visionary energy of the young—though this is one of those texts that, in my Children’s Literature classes, we’d be cross-examining to see what its construction of youth says about the hopes and needs of adults. While 5 Worlds depicts young people as radically free, it follows a didactic agenda that tries to teach young readers to be those free spirits, and to save us all. Ultimately, it rejects the shaded, tragically complex vision of one its avowed inspirations, Miyazaki, in favor of an unequivocal ending in which hesitation and gradualism can be identified with a hated Dark Lord and summarily banished. It’s all about the certainty of Truth. Yet the skeptic in me wants something a shade more tangled and complicated. In the end, I found myself wondering if the utopianism of 5 Worlds conflicts with some of the messages it has been trying so hard to convey. But, oh, what a rapturous five-year ride.

0 Comments

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

Archives

June 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed