|

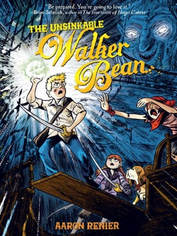

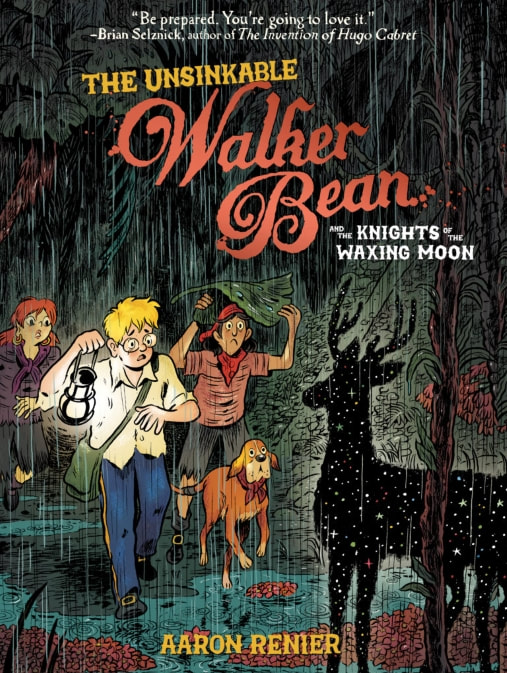

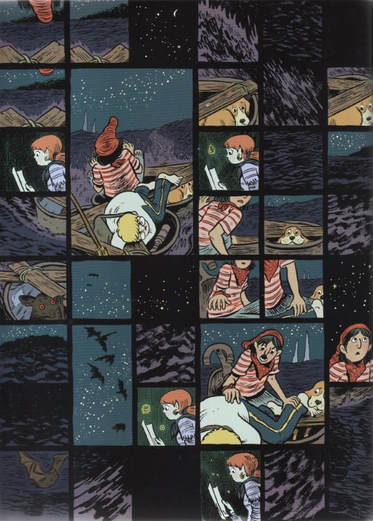

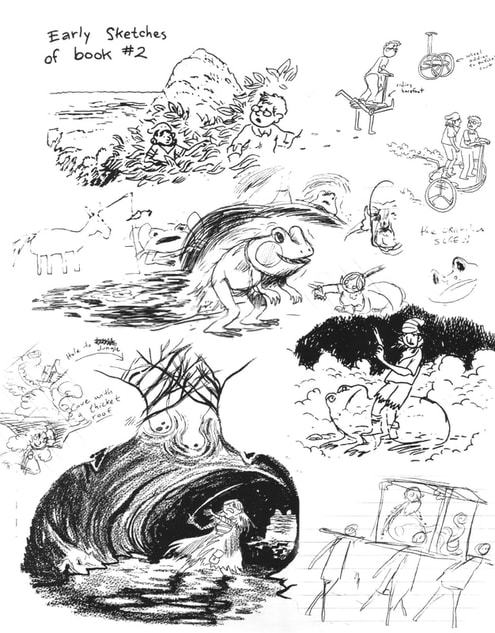

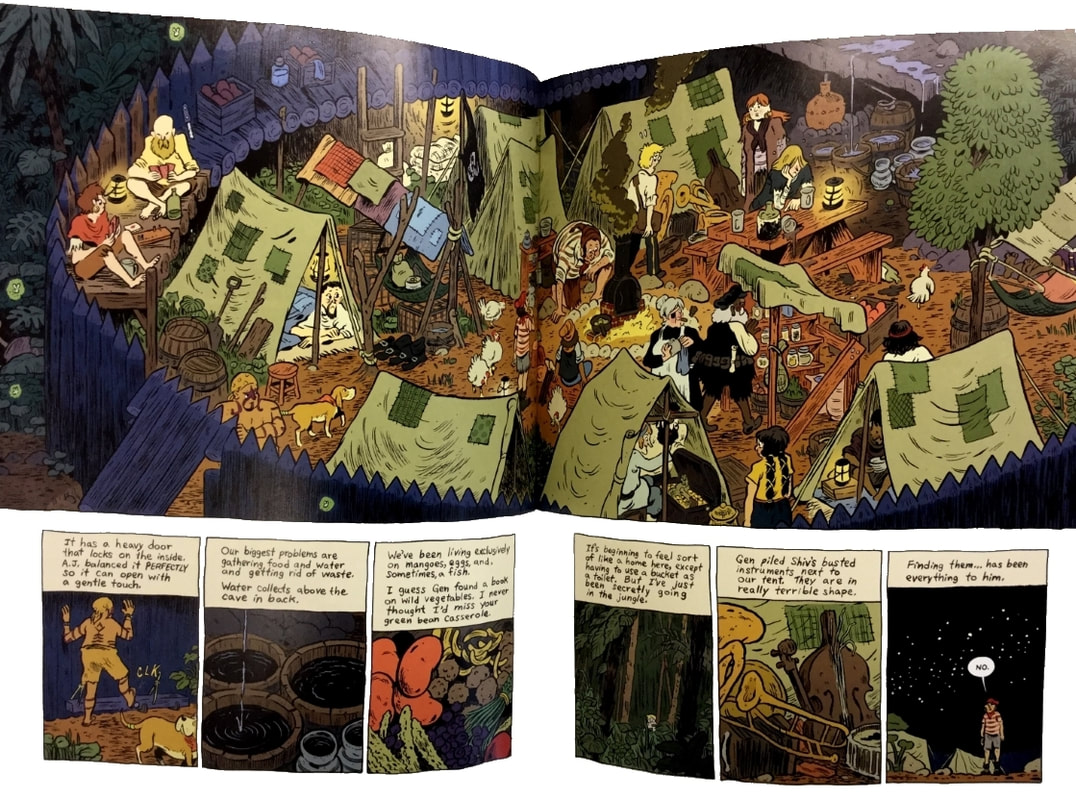

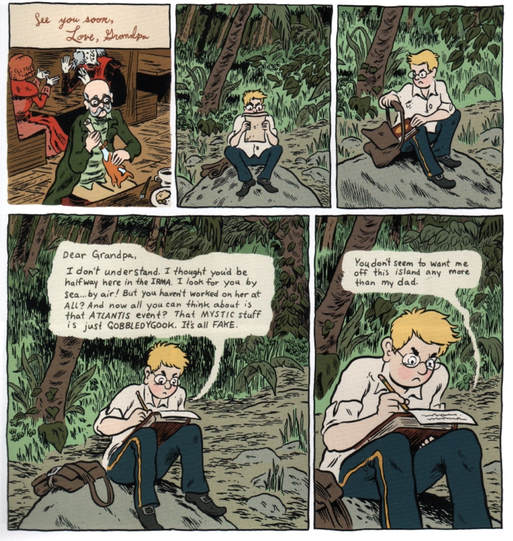

The Unsinkable Walker Bean and the Knights of the Waxing Moon. By Aaron Renier. First Second, 2018. ISBN 978-1596435056. 288 pages, softcover, $18.99. Colored by Alec Longstreth. Eight years ago—my gosh, eight years ago—author-artist Aaron Renier and colorist Alec Longstreth gave us The Unsinkable Walker Bean, a gobsmacking pirate yarn and reckless feat of cartooning. It was, is, absurd and terrific, overfull and bursting with notions. Far-fetched and outrageous, rigged to the point of obsessiveness, it’s also generous and heartfelt, and a gushing testimony to Renier’s love of world-building. Reviewing it was a thrill. Now Renier and Longstreth are, yes, back with a second Walker Bean book that I can only describe as more of the same, but longer and even more ambitious: The Unsinkable Walker Bean and the Knights of the Waxing Moon, an adventure at once hectic and transporting, overbusy yet oddly soulful. When I first read it, it drove me a bit nuts, so mazy and bewildering is its plot. When I re-read it, though—well, I think I got it. The world of Walker Bean consists of salty pirate tales (in the Stevenson tradition) blended with high fantasy. It takes place in an odd variation on the known world that mixes real and invented geography, in an unspecified period that feels like a dreamlike rewriting of the nineteenth century. Walker is a shy, bookish boy, frankly a nerd: brilliant, but fragile and sensitive. People treat him as a softy, but he has steel in him; on the other hand, he can be a bit of a pill. Most unwillingly, Walker gets pressed into nautical adventures that carry him far from his home on Winooski Bay and introduce him to supernatural forces and secret histories. The first book concerned a magical skull, two monstrous “sea-witches,” and a seafaring quest, much of it aboard a tricked-out ship called the Jacklight, which could travel over land as well as wave. In that one, Walker was joined in his travels by Shiv, a powder monkey, and Genoa, an intense and mysterious adventuress. They are still together in the new book, and make for a sturdy triad (in a sort of Harry-Ron-Hermione way). Knights of the Waxing Moon shares the spirit of its predecessor, and offers continued treasure-hunting, with many of the same characters (as well as many new ones). But there’s less sailing, now, because the story takes place mainly on the same haunted archipelago where Walker and friends were stranded at the end of the first book: the Mango Islands. Basically, this is a “mysterious island” tale. Something happened on the archipelago long ago, something that still casts a long shadow. Competing treasure-hunters, some much older than they appear, seek a source of power—a magical metal—and again supernatural agents and occult histories are high in the mix. Mistaken identities play a part, as do bemusing visits to the past. Mysterious shadow-beasts that guard the islands add a whiff of Miyazaki: the environment seems neither benign nor malevolent, but sublime and indifferent. As in the first book, the stakes are high, the violence consequential, and the scares properly scary; Walker and friends experience sadness, anxiety, and loss along with ripsnorting adventure. If I faulted the first Walker Bean for getting lost in its unlikely, careening plot, I have to say the same of the second. Plot-wise, Knights is the equivalent of juggling cutlasses and cannonballs—tricky, that is. I confess that on first reading I had trouble following the story’s logic, its links and reversals, its mad, ambitious sprawl and ballooning cast of characters. In fact, I finished my first reading—a breathless, late-night binge—in a knot of frustration. For a moment, I thought of the book as a failure: a dream that had gotten hopelessly blurred en route. Hallucinatory flashbacks, inscrutable clues, magical MacGuffins, and sudden, disorienting setpieces, not to mention the many new characters, make Knights a challenging, even frustrating tangle. Transitions are often abrupt, and essential details and connections are sometimes left for the reader to intuit. The relationships among the characters are not easy to chart: motivations are shaded, and alliances form or fail on the spur of the moment. Doppelgangers and ghosts abound. Our three young heroes are called upon to change, and Genoa in particular goes through a startling self-discovery. So, there’s a lot to take in. A lot. So confounded was I by my first reading that, in defiance of my schedule and good sense, I reread the book immediately—and reread the first book too. The second time around, Knights seemed to click: I grasped a number of hints and foreshadowings, better understood certain transitions, and, in sum, could more easily negotiate the plot-rigging. If on the first pass Knights seemed jumbled, with a hiccoughing rhythm and befuddling climax, on second read the book revealed an insinuating story with elaborately braided details, a designing shape, and knowing callbacks to its predecessor. As a self-standing graphic novel, Knights may seem overdense, or over-egged, but as one leg in a longer journey, a further unveiling of a big, big world, it’s a marvel.  Although Knights spins its own distinctive yarn, it does require readers to know the first book intimately (not for nothing did First Second reprint the first a few weeks ago). It refers back to its forerunner constantly, in ways both obvious and subliminal—and this was part of my problem on first reading, because I needed the first book in front of me in order to follow the second. Some of these callbacks fulfill mysteries teased out in the first book, while others deepen the mystery, or extend the original’s meaning. Knights, in short, asks to be read alongside its predecessor. At the same time, it outdoes the first book for scale and strangeness: for one thing, it’s about a hundred pages longer. Even then, it seems more compressed, with (often) denser layouts and too-small balloon text. Still, it’s an organic outgrowth of the first book. Revisiting the first, I notice that its back matter includes teasing “sketches of book #2,” and sure enough I do see elements that made it into Knights: Renier clearly had some of this second book in mind more than eight years ago. Knights, then, is both a close sequel and yet its own strange animal. The trickiness of the book’s plot may prove a trial for readers. Yet I take some delight in the way Renier refuses to talk down to us. Clearly, he digs a nested, baroque plot. In fact, his approach to story recaps, on a larger scale, the complicated maps, diagrams, and inventions that he so lovingly draws into the book. I like that. Still, I’d say that the plot is too compacted, and its logic a bit too implicit; this 280-page yarn packs in 500 pages’ worth of complication. At times Knights surrenders clarity for momentum, and, like the first book, sprints through transitions and critical moments that rather beg for a long double-take. What’s more, certain details are left dangling--bait for the next sequel, presumably, but maddening. For example, one of the book’s narrators, a crucial source of exposition, is left shadowed and unidentified, and Walker’s unscrupulous father, briefly glimpsed, remains a nagging loose thread. (I dearly hope it won’t take another eight years to tie off that thread.) More than anything, a passion for worldmaking through drawing animates the Walker Bean books, and on that score Knights of the Waxing Moon matches its forerunner. It piles up, graphically, vividly, a surplus of environments and space, creatures and ships, devices and talismans, all rendered with breathless excitement. Renier, as he zooms ahead, leaves behind a trail of small delights: details that pop out upon rereading, to be savored or puzzled over. In fact the galloping momentum of the story and the luxurious world-building are at odds, making the book at once a sprint and a sightseeing tour, a plot-driven adventure and a dungeon master’s guide (oh man, Walker Bean is a role-playing game just waiting to happen). Judged by the standards of tight, Tintin-esque adventure, the book is a failure—it packs in too much stuff to attain that kind of crystalline form—but as a celebration of drawing worlds into being, man, it’s something. Renier and Longstreth once again turn out beautiful pages and spreads, with a loose, feeling line and sumptuous palette; at the same time, Renier tries out new things in layout, pacing, juxtaposition, and braiding. A labor of love, I cannot help but think. Love and feeling are big for Renier. Both Walker Bean books brim with emotion: characters weep, fret, and startle—gulping, gasping, reacting. They sometimes panic. They get on each others’ nerves too, reproving and arguing with one another. They worry for each other. Walker and his cohort, and even the heavies, wear their emotions near the surface, and many scenes are raw with feeling. Even the quietnesses can be supercharged. Take for instance this loaded moment from early on, as Walker, feeling abandoned, starts an angry letter to his beloved Grandpa, but then thinks better of it: Scenes like these show that Renier values not only the pleasures of drawing but also the vital emotive connection between characters and reader. Some of the relationships in Knights are tumultuous—in fact, testing or reaffirming friendship in the face of severe trials is a large part of what the book is about. The sheer feelingness of Walker Bean is a necessary balance to the baroque plotting and ecstatic drawing. Renier cares about his adventurers, and faithful readers will too. Structure-wise, Renier may be aiming for the kind of unfolding epic that Jeff Smith crafted in Bone. Feels like it. But he isn’t working within the same serial format, one that allowed Smith an unhurried pace, a gradual unspooling and deepening of his imagined world. Nor is Renier publishing with the same momentum as, say, Kazu Kibuishi, whose Amulet series has yielded eight roughly 200-page volumes in a decade. The Walker Bean books are different: jam-packed, overstuffed, sort of obsessive. They bespeak, again, a love of drawing and knotty, puzzle-like storytelling. Renier, I think, loves world-building in a way that can barely be corralled into sensible, well-structured volumes (though he does strive mightily after an overarching structure). His penchant for overstuffing recalls, for me, Mark Siegel et al.’s elaborate 5 Worlds series, except it’s less mediated, more personal: not the result of a carefully managed collaboration that subsumes individual quirks, but the result of one artist running wild. And, you know, I kind of love him for that. Readers who loved the sheer outrageous overspill of the first Walker Bean will also dig the second. Me, I’ll reread these books and take pleasure in them, again and again. In this age of well-shaped, well-behaved, and precisely marketed graphic novels for children, Walker Bean is exceptionally weird, hence wonderful. My gosh, I hope for a third volume. And more.... First Second Books provided a review copy of this book.

0 Comments

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

Archives

June 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed