|

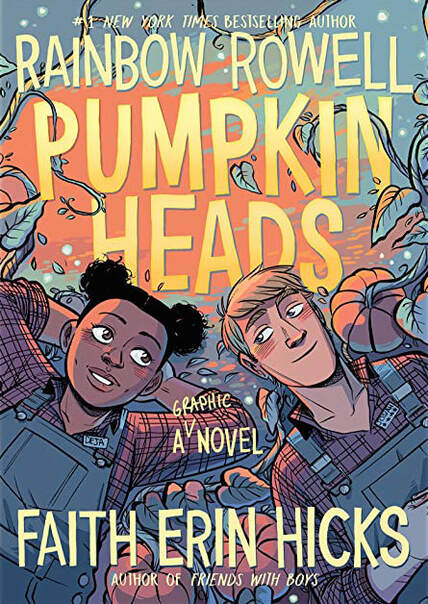

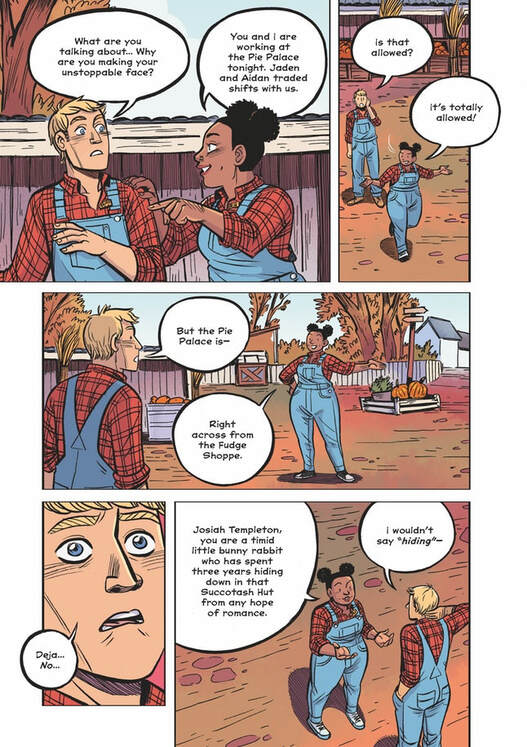

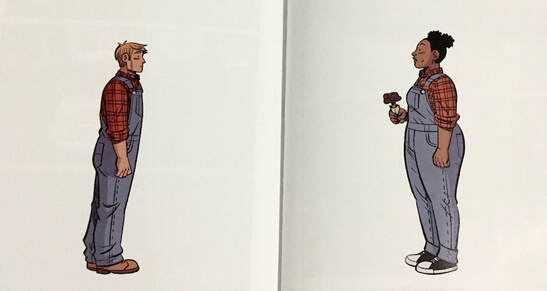

Pumpkinheads. By Rainbow Rowell and Faith Erin Hicks. Color by Sarah Stern. First Second. ISBN 978-1626721623 (softcover), $17.99; ISBN 978-1250312853 (hardcover), $24.99. 224 pages. Pumpkinheads is a breeze of a graphic novel: a busy, boisterous story of roughly six hours shared by two high school seniors one Halloween night. It follows Deja and Josie (Josiah), two seasonal workers at a Midwestern pumpkin patch (replete with corn maze, hayrides, petting zoo, etc.). Deja and Josie are wistfully anticipating graduation and goodbyes, but insist on sharing this “last” Halloween together, which turns out to be a bit of a crazy night. What starts with a gesture of farewell ends by hinting at the possibility of shared times to come. Deja, who seems to have dated every other girl and boy at the patch, comes across as the more socially conscious and proactive of the two, while Josie, a “most valuable” employee and pumpkin geek, is shy, passive, and obtuse. Deja aims to help Josie talk to another patch worker, a girl he’s been mooning over fecklessly for the past three years—this may be his last chance to break out of his shell and strike up a relationship with her. Yet finding that girl in the big sprawl of the patch proves a challenge, as the two run into one colorful mishap after another. Outwardly, the suspense has to do with getting Josie to that girl, but what really matters is the relationship right in front of us: Josie and Deja. The book hints and hints at the special nature of their friendship—will they recognize it before the night is through? Deja and Josie are complementary opposites, but both love, in an unselfconsciously nerdy way, the corniness of the pumpkin patch and its attractions. Where they differ is in their attitudes toward sociability. Josie is the type to wait for good things to come to him — he doesn’t know how to initiate a relationship — but Deja tells him that he must make choices and act on them if he is to get anywhere with anyone. The plot consists mainly of their walking, talking, and solving minor crises at the patch: together they run into various of Deja’s “exes,” navigate the fudge shoppe, s’mores pit, and corn maze, and reunite a lost child with her mom. There’s a lot of funny, rowdy action, but, again, what matters is their dialogue, which telegraphs an unacknowledged depth of feeling between the two. We readers perhaps get to know them better than they know themselves. Scriptwriter Rainbow Rowell captures the offhand, familiar quality of friendly banter; you can believe that Deja and Josie have known each other for a long time. Cartoonist Faith Erin Hicks supplies (as the book’s back matter makes clear) the layout and rhythms, pacing and punctuating the action with wordless panels full of significant glances and sly, well-observed business. Theirs is a felicitous collaboration, intently focused on the two leads, their comical backdrop, and their dawning self-awareness. The results are seamless and fun to read. Pumpkinheads is perhaps thematically slight, reflecting Rowell’s stated desire to do something “light and joyful.” It may be utopian; certainly it's idyllic and matter-of-factly progressive. Tonally, the book echoes many middle-grade stories that anticipate high school without the critical awareness of social power and inequity typical of YA fiction. Set in an idealized Midwest, it skirts questions of racism and homophobia (Deja, a queer young woman of color, is treated as wholly accepted and socially unremarkable). Implicitly, the book promotes body positivity: Deja is (as Rowell describes her) chubby, and one scene deals subtly with fat-shaming, but her beauty and vivacity are never in doubt. Josie, in contrast, is the very image of cornfed white Midwestern handsomeness. The supporting cast is discreetly diverse (though we learn little about them). Mainly, this is a charming story about discovering the depth of a relationship, equal parts ebullient comedy and quiet romance. Rowell and Hicks understand and love their characters, and Hicks draws their interplay with a keen eye for pauses, insinuations, and unspoken currents of feeling. In the end, Pumpkinheads is succinct, pleasant, and remarkably well crafted: a model middle-grade graphic novel, thematically unexceptional maybe, but sweetly human.

0 Comments

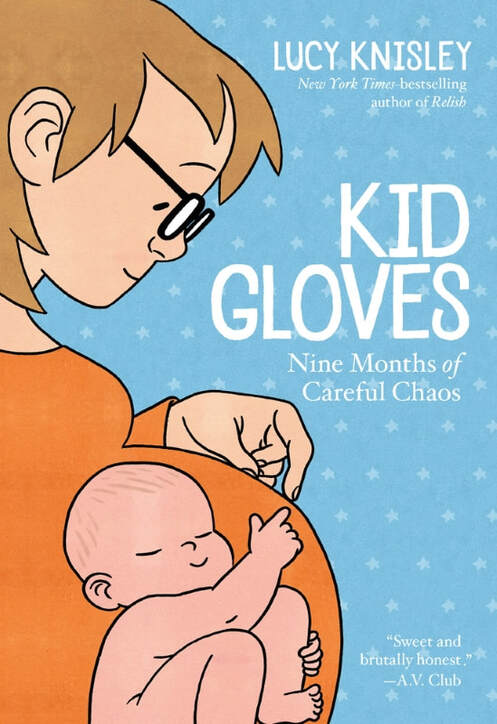

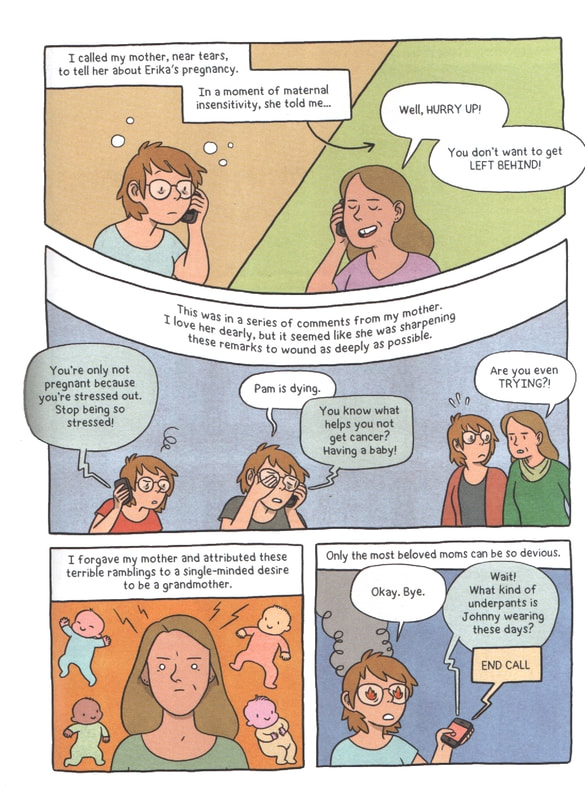

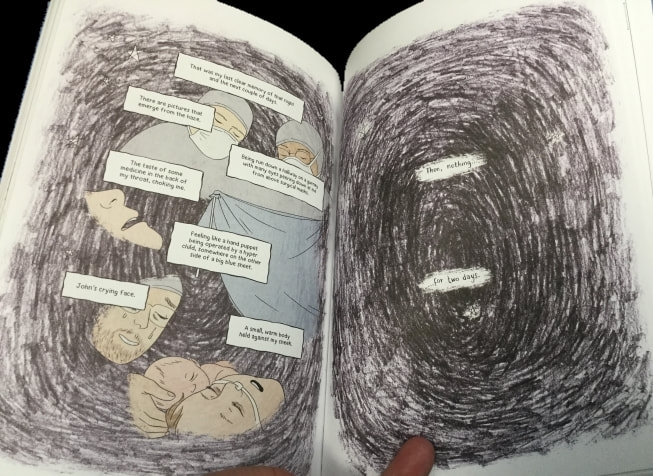

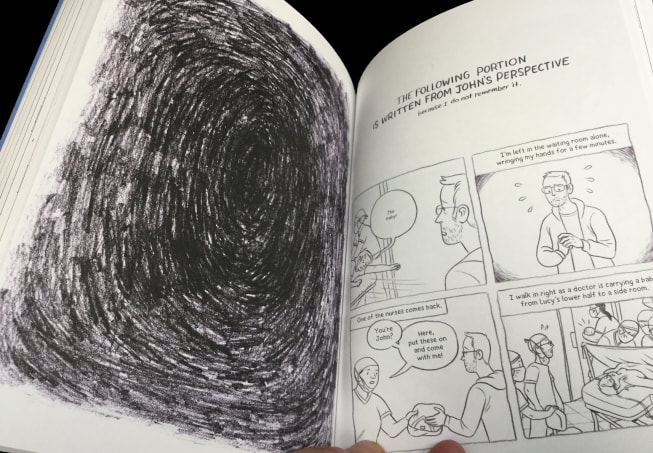

Kid Gloves: Nine Months of Careful Chaos. By Lucy Knisley. First Second. ISBN 978-1626728080 (softcover), $19.99. 256 pages. Kid Gloves tells of author Lucy Knisley’s pregnancies and miscarriages, and finally the birth of her and her husband’s child. Blending memoir, childbirth education, and self-help, the book also offers, at times, sharp criticism of both sexist birthing institutions and natural childbirth truisms. Between chapters of personal narrative, Knisley inserts brief interchapters devoted to “pregnancy research”—actually, a mix of contextualizing details and Knisley’s pointed editorializing: often humorous, sometimes exasperated. These interchapters are didactic but droll, and not impersonal; they resonate with Knisley’s own story. The larger personal narrative takes us through Knisley’s miscarriages and resulting depression, then on through the conception, bearing, and delivery of her child—itself a traumatic, life-threatening event (due to eclampsia and seizure). A lot of scary stuff is replayed in this story, but also a great deal of joy and good humor. Knisley comes across as a friendly but not uncritical guide to the vagaries of pregnancy, opinionated, blunt, and confidential. She relays her story from a safe retrospective distance: her introduction shows Lucy and the baby, weeks after delivery, doing okay, and the narrative captions reassuringly carry us along. That is, the story is recounted in hindsight, rather than rawly dramatized. All this is delivered (sorry!) via Knisley’s reliably excellent, toothsome cartooning, dynamic yet readable layouts, and beautiful colors—signs of her offhand mastery of the craft. Wow, can she make comics. I admit I approached Kid Gloves a tad nervously, unsure of whether Knisley’s writing would be equal to her subject. My first experience of her work, her memoir Relish (2013), had frustrated me with what I took to be its unexamined entitlement, skirting of emotional complexity, and preference for glib affirmation over fierce self-examination. Knisley does not do raw confessionalism or self-damning underground memoir. While her work does take on hard things, she tends to adopt a position of earned confidence and matter-of-factness (again, self-help is a useful point of reference). Her rhetorical construction of self is not the fractured self of Green or Kominsky-Crumb, nor the compulsively self-questioning, reflexive self of Spiegelman or Bechdel (though she does indulge here in comically grotesque caricatures of her changing body and its trials). Knisley the narrator seems secure even when Kid Gloves depicts the depths of depression or the harrowing trials of illness and emergency. It is a reassuring sort of memoir that offers a sane perspective-taking rather than an unsettled, open-ended questioning (in this, it reminds me of what Ellen Forney has done in her memoirs of bipolarity). Indeed, at times Kid Gloves skates over complex things much as Relish did. For example, in a sequence that my wife Michele called to my attention, Knisley recalls the aftereffects of one of her miscarriages, and what she characterizes as her mother’s insensitive response: You might think that this characterization would lead to a considered treatment of her mother throughout the remainder of the book, one that would balance daughterly love and forgiveness against frustration and critique. But Knisley accepts this tension between mother and daughter as an unresolvable, and moves on, not revisiting these hard feelings but tucking them away. (You won’t find here, for example, the extended, ambivalent treatment of parent-child relationships that you’ll see in Thi Bui’s The Best We Could Do.) I worried that this key moment, which comes early in the text, would cancel Knisley’s piercing depictions of depression, that she would paper over complexities in the quest for a feel-good equanimity such as we so often see in popular memoir and self-help books. Knisley, however, proved me wrong. Her narrative goes on to address challenging issues, including her and her husband’s anxieties, her triggers and preoccupations, the wrenching bodily demands of pregnancy, and her tense relationship with childbirthing dogma. The actual birth of her son, accomplished by cesarean and blurred out by medication, brings an explosive change to Knisley’s pages, suggesting lingering trauma and loss. Further, when her own life hangs in the balance, Knisley switches focalization to her husband, with drastic changes in her technique. There are moments when her always decorous, conspicuously well-designed pages become unsettled and the delivery of her story becomes most piercing. The book’s climax moved me beyond my expectations. Michele read Kid Gloves before I did, and told me frankly that the book raised up some difficult memories for her. This was perhaps another reason why I approached the book with a bit of dread. It’s true that reading it brought up some of my own memories of how Michele and I wrestled with medicalized childbirth and its outcomes. Frankly, I was surprised by how much Knisley criticizes natural childbirth rhetoric and embraces what she calls “hospital-based interventions” (even as she recounts what were arguably cases of medical malpractice). Kid Gloves, it's fair to say, takes a jaded view of the power struggles between obstetrics and traditional midwifery. These notes brought up memories of our own childbirthing experience; they also got me to question Knisley's wisdom. At times, the old feelings of impatience regarding her writing came back to me. There was a whiff of unexamined entitlement about Knisley's weighing of women’s “choices” in childbirth (“as long as everyone’s healthy”), and behind her settled self-presentation I sense a certain hardheadedness. But, still, Kid Gloves is a forthcoming and bracing story, one that will surely prove inspiring to many readers going through the childbirthing experience or seeking to put it into perspective afterward. By book’s end, I felt grateful for the ride. In sum, Kid Gloves uses the all-at-onceness and richness of the comics page to tell a story that is at once personal, instructive, and political. I don’t quite love it the way I love comics that tell of childbearing from a rawer, less protected place (check out Lauren Weinstein’s superb Mother’s Walk), and I note that Knisley continues to walk the knife’s edge between personal exploration and tidy, marketable endings. But Kid Gloves marks a step forward for her as a writer, and I recommend it.

KinderComics, alas, has been away for too long. This spring and summer, I have had to channel my energies elsewhere. I hate to admit it, but my academic-year workload does not make room for frequent blogging, and when the summer or intersession comes around, well, then I end up having to advance or complete other long-simmering projects. Lately I’ve had to cut back, refocus, and make a point of not driving myself nuts! Still, I am going to push for several reviews this summer; I want to keep KinderComics alive. The field of children’s comics is too important, and my interest in it too intense, to let go. I’ll have a review of 5 Worlds: The Red Maze up later this week, and then a few (probably short) ones between now and Labor Day, in order to keep the engine humming. Thank you, readers, for checking out or revisiting KinderComics. I’ll keep pushing. There has been a great deal of news on the children's comics front during my four-month absence. Would that I could go into all these stories in detail:

Besides all that news, awards have been given out:

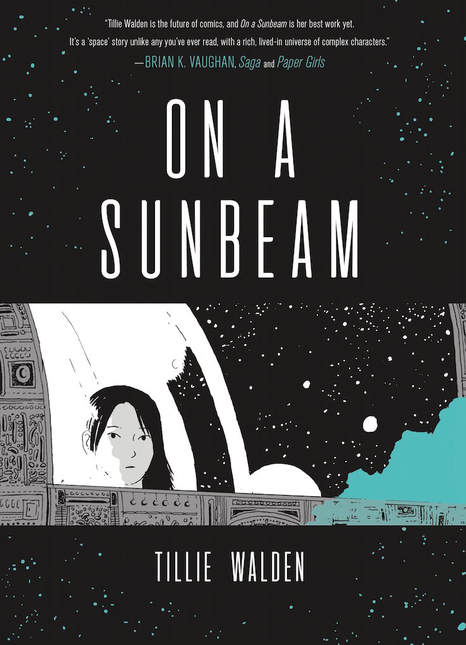

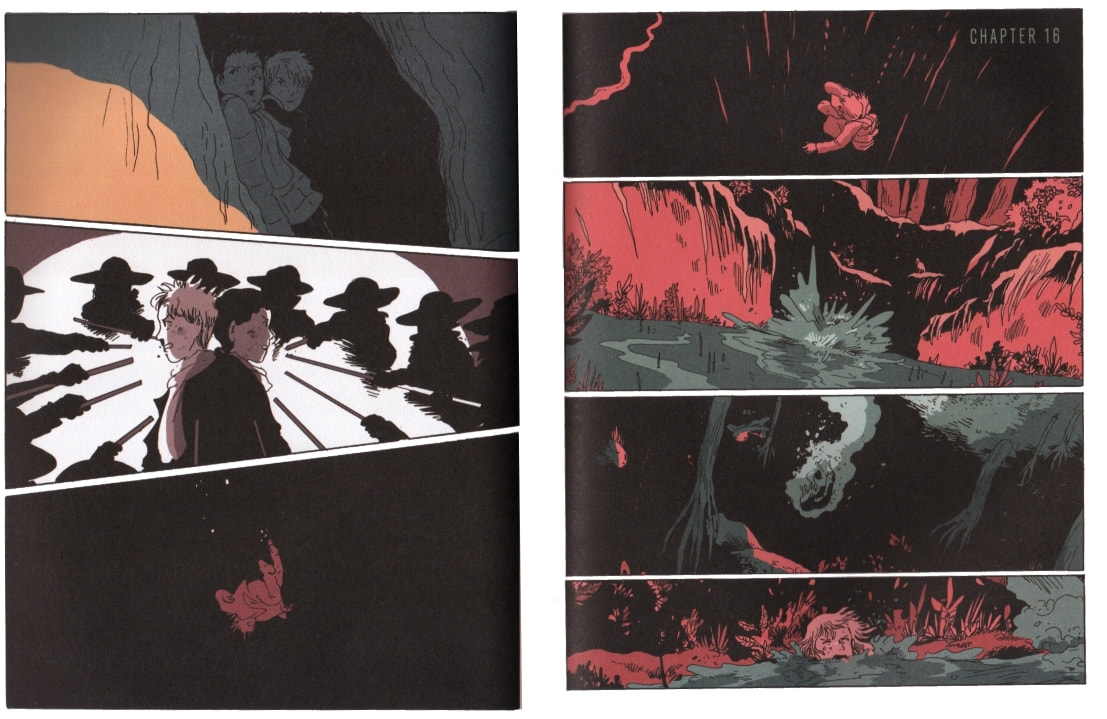

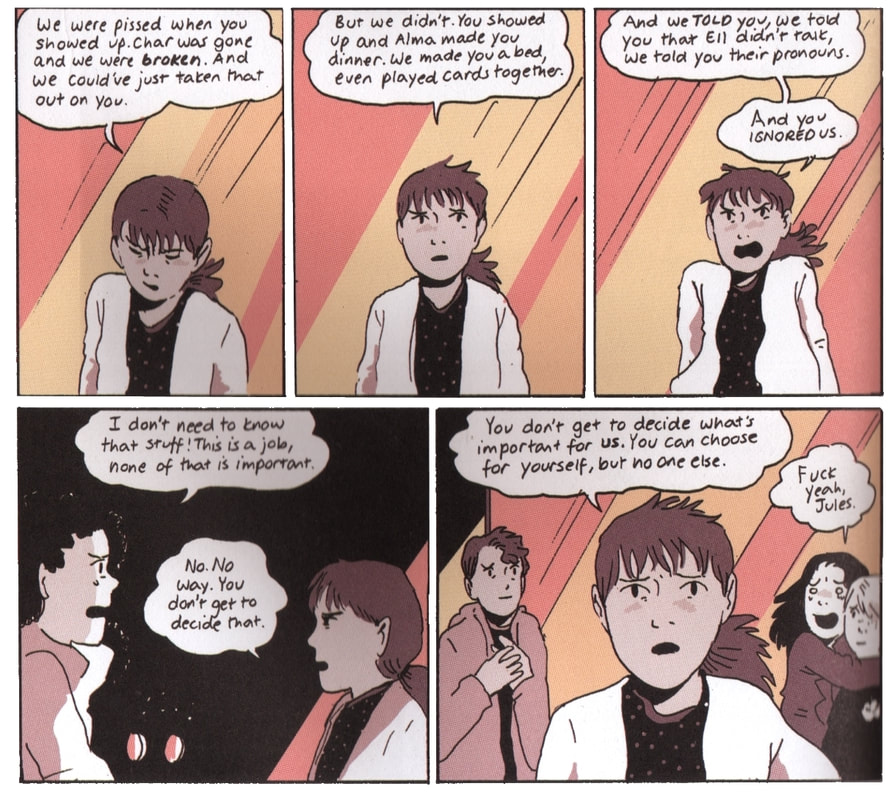

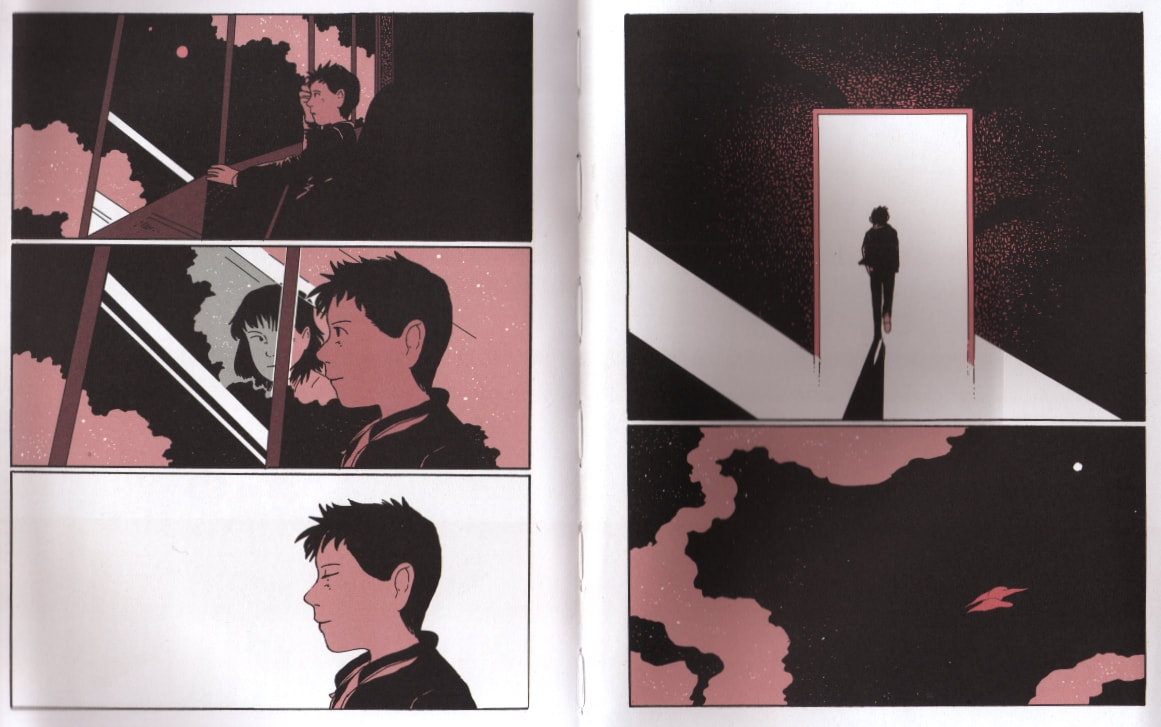

My gosh, what a busy and exciting field. Keeping up is a challenge! I hope to do a better job going forward. A sad postscriptWhen it comes to public-facing scholarship and comics criticism, one of the most inspiring figures to my mind was the late Derek Parker Royal, co-creator, producer, and editor of The Comics Alternative podcast. Derek, a major critic of Philip Roth, Jewish American literature and culture, and graphic narrative, passed away recently, leaving a grievous sense of loss in the hearts of many. He was a scholar, innovator, and facilitator of a rare kind, generous, engaged, and prolific, and will be greatly missed in the comics studies community. He brought many people into that community; for example, at the Comics Studies Society conference in Toronto last weekend, his longtime collaborator Andy Kunka spoke movingly of how Derek encouraged him to enter the field. I will think of Derek whenever I post here, and the soaring example that he set. RIP Derek. Thank you for your scholarship, your advocacy, and your spirit.On a Sunbeam. By Tillie Walden. First Second, 2018. ISBN 978-1250178138. 544 pages, softcover, $21.99. Tillie Walden has an uncanny gift for, and dedication to, comics. Her newest book On a Sunbeam (compiling and adapting her 2016-2017 webcomic of the same name) is a gift in itself: a queer romance that starts as a young adult school story—an acute exploration of tenderness, social anxiety, and the keeping of secrets—but then blossoms into a breathless adventure tale. At the same time, it's a paean to queer community and found family, while also being, wow, a space opera. I'm not kidding. In other words, On a Sunbeam is a miracle of genre-splicing and of unchecked, visionary cartooning—one in which Walden does whatever she wants, while yet upholding a traditional, eminently readable form. As soon as I got a copy, I was pulled along, pretty much helpless, for an ecstatic 540-page ride. The story ought not to work, in theory. On a Sunbeam is galaxy-spanning science fantasy in an undated future, one governed less by grounded scientific extrapolation, more by poetic metaphor. The spaceships resemble fishes, swishing across the skies and through the cosmos on fins. Buildings float through space looking exactly like earthbound buildings: a church, say, or a schoolhouse. This is deliberate; Walden treats space like terrestrial geography, only bigger. Ditto architecture. Much of the action involves the repair of damaged or derelict buildings out in space, by a "reconstruction" team whose job falls somewhere between renovation and archaeology. They deal in statuary, stone, and tile as well as high tech. Often the settings don't feel like "space" at all—until they do. No one wears spacesuits, though everyone's bodies must somehow adjust to being in deep space. Oh, and the cast seems to consist solely of women and genderqueer characters. What sort of universe is this? To hell with what would work "in theory." The story, for its first 2/3 or so, shuttles back and forth between two main settings: an upper-crust boarding school (in space), and the Aktis (or Sunbeam), the reconstruction team's spaceship. But it also shuttles back in forth in time, across a gap of years: the "school story" part of the plot happens in flashback, five years past, while the story's "present" follows Mia, formerly of the boarding school, now a (green) member of the Aktis crew. Walden skillfully uses layout and coloring variations to set these two timelines apart (and ultimately to bring them together). What really ties these timelines together is the bond between Mia and her schoolmate Grace, a socially withdrawn girl of unknown origins. Grace and Mia share a romance that is tender and profound: a genuine love story. However, their bond breaks when Grace is mysteriously summoned home from school. Her home is an enigma. Mia longs to see Grace again, but the years go by and a reunion seems impossible. About midway through the book, though, Mia and her Aktis family undertake a fantastical quest for Grace's homeworld, tying the book's several plotlines together. The final third brings the Aktis (and us) to an otherworldly setting worthy of Jack Vance or Keiko Takemiya. On a Sunbeam has tremendous emotional and tonal range. The anxious school scenes of the first half capture budding relationships, first steps toward intimacy, and uneasy social maneuvering, resonating with Walden's great memoir Spinning. The bonding of Mia and Grace recalls, for me, the lyrical evocation of young and growing love in the book that introduced me to Walden, the dreamlike I Love This Part. Walden is great at conjuring the rivalries and vulnerabilities of young women in social groups, the tension between ringleaders and outliers, and the no-bullshit demeanor of girls among girls, at once strong and fragile. On a Sunbeam carefully builds the relationship of Mia and Grace, two believably different young women, into a deep, unqualified love; their unspoken understandings and gestures of mutual care and self-sacrifice make them a couple to root for (and the book, delightfully, suggests that queer romance is common in their school and world). Yet Mia's later initiation into the Aktis crew creates other deep relationships, both among the crew and between Mia and every other member. The tenderness of the Grace/Mia dyad suffuses everything that comes after, and what begins as a rough, contentious team gradually becomes, emphatically, a family, one of Mia's own choosing yet defined by complex bonds with and without her. The book's range broadens dramatically in its final third, as the plot upshifts with a vengeance: Walden leaps headlong into phantasmagorical SF, but also abrupt, jolting violence, frenzied cross-cutting, and nail-gnawing suspense. This is the very stuff of pulp adventure, yet made more urgent by a reservoir of earned emotion. Lives are risked, a world uncovered, and secrets revealed (my favorite being the backstory of Ell, the ship's non-binary mechanical whiz). I could hardly hold on to my chair during the last hundred pages! Yet mostly On a Sunbeam is a story about love. The word that keeps coming back to me is tenderness, and Walden hits the tender spots again and again, not with cynical knowingness but with the thrilled self-discovery of an explorer who has just realized what her explorations are about. Relationships deepen, and at some point we realize—that is, Walden shows us—that On a Sunbeam is not simply the story of a single idealized love but of loving community, and of what it means to take others as they are. It's a story about unlike people forging bonds of mutual respect and care. Among the many exciting climaxes in the book, the most important ones, to me, are embraces. On a Sunbeam wears its heart on its sleeve. All this is delivered with the utmost grace, with a style whose delicacy reminds me of C.F. (Powr Mastrs) and whose out-of-this-world gorgeousness calls to mind Takemiya and Moto Hagio, those masters of shojo manga SF. Remarkably, Walden's style hardly ever betrays signs of underdrawing; the characters and panels seem to have found their perfect form without hesitation. Her style might be considered a variation on the Clear Line—clean contours, no hatching, and the use of contrasting solid blocks of color to solidify form—but without the cool meticulousness and literal, mimetic colors that such a comparison would imply. She's freer, and her light, unfussy lines are elegance itself. This is the more remarkable because her characters, emotionally, are all about undercurrents and anxiety; Walden renders their struggles with an unerring economy even as they're going through hell. Open white space, blocks of color and of darkness, the selective paring of background details—all these artistic strategies bring the story into crystalline focus. The spareness and cleanness of Walden's pages belie, or rather render all the more piercingly, the struggles going on among and within her characters: In my comics classes, I like to say that every book of comics teaches you how to read it, becoming its own instruction manual. That is, no generalized understanding of "comics" as a whole is going to make every new comic you encounter easy to understand, because comics aren't as formally stable and consistent as that. Instead, the form shifts, or artists shift it, toward new strategies and purposes—but attentive readers will learn how to read in a comic's particular way. I think about this when I see pages like the above, or On a Sunbeam's climactic pages: Coming at these pages unprepared, sans context, I would hardly know how to read them. But it's a testament to Walden's skill, and the gripping human story she tells, that these spare pages speak volumes to me now. On a Sunbeam is full of payoffs like this; it's masterful. It's also moving and exhilarating. As I said, uncanny. PS. I was sorry to miss Walden's conversation with Jen Wang at L.A.'s Chevalier's Books on Oct. 8. But I look forward to her signing and exhibition at Alhambra's Nucleus gallery on Feb. 22. First Second Books provided a review copy of this book. (Note: It was particularly challenging to scan pages from On a Sunbeam, a roughly 6 x 1.5 x 8.5 inch brick!)

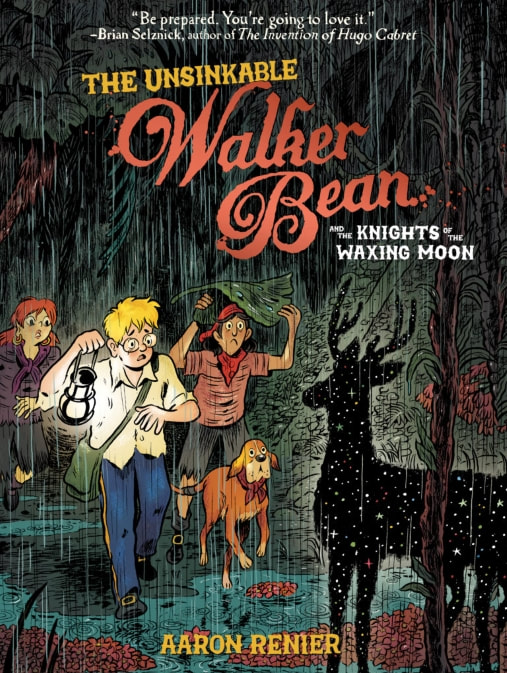

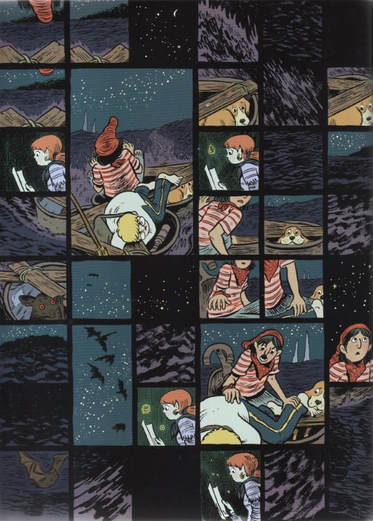

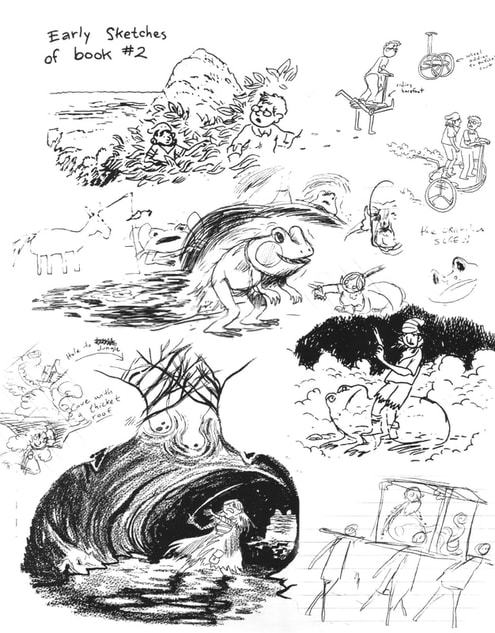

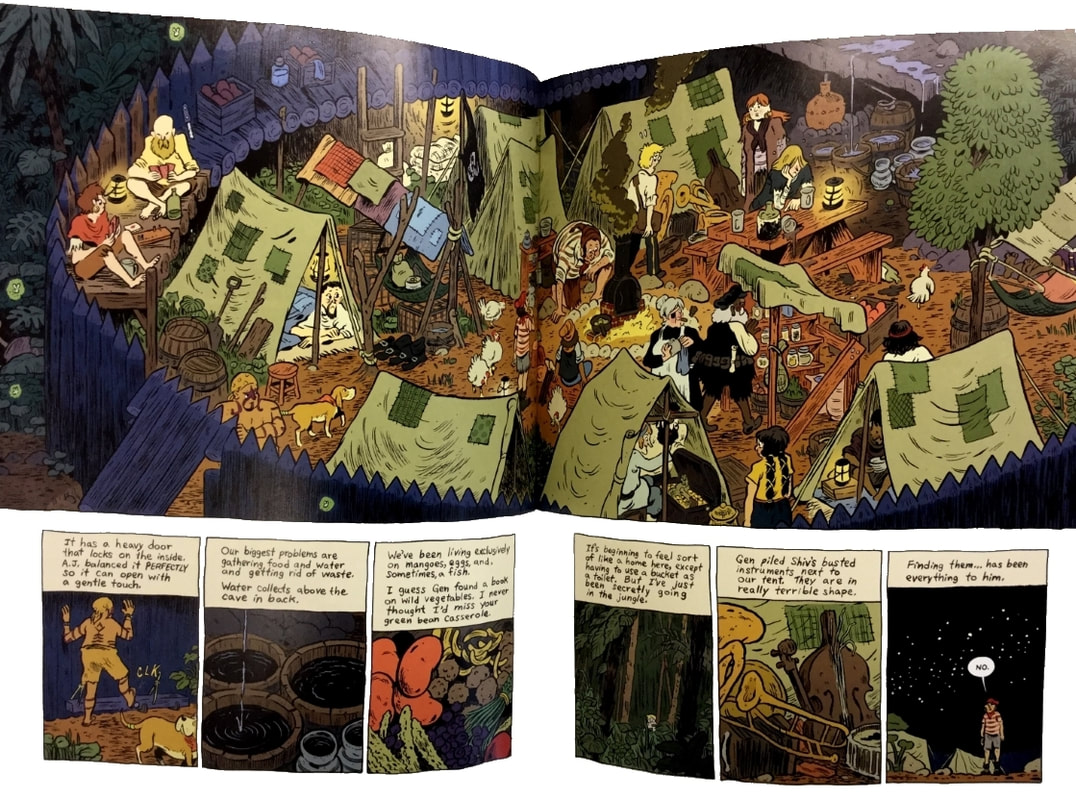

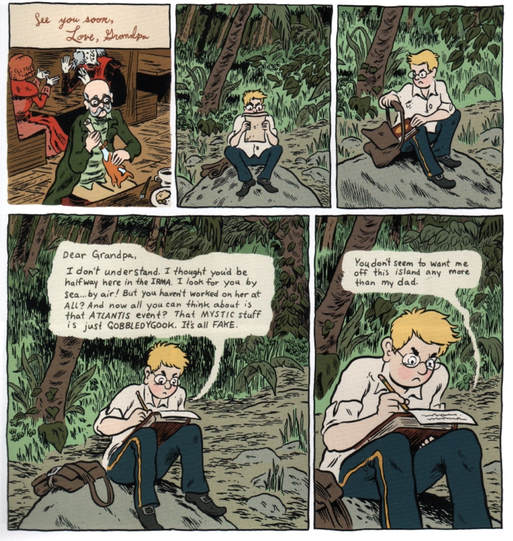

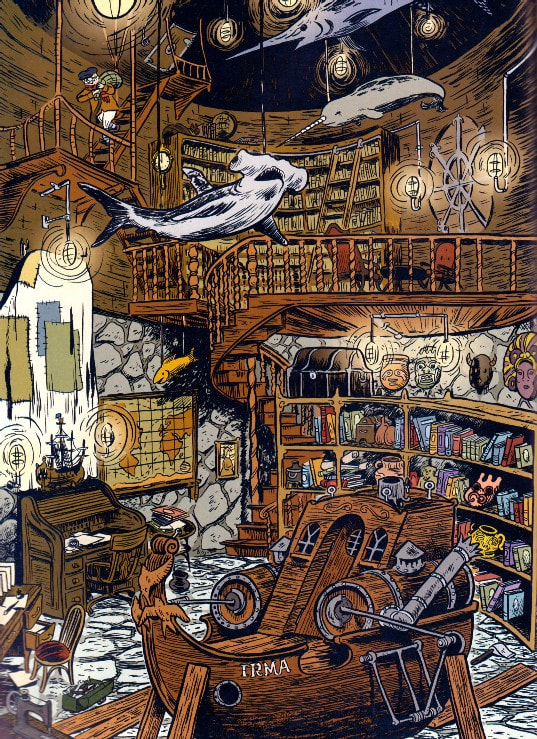

The Unsinkable Walker Bean and the Knights of the Waxing Moon. By Aaron Renier. First Second, 2018. ISBN 978-1596435056. 288 pages, softcover, $18.99. Colored by Alec Longstreth. Eight years ago—my gosh, eight years ago—author-artist Aaron Renier and colorist Alec Longstreth gave us The Unsinkable Walker Bean, a gobsmacking pirate yarn and reckless feat of cartooning. It was, is, absurd and terrific, overfull and bursting with notions. Far-fetched and outrageous, rigged to the point of obsessiveness, it’s also generous and heartfelt, and a gushing testimony to Renier’s love of world-building. Reviewing it was a thrill. Now Renier and Longstreth are, yes, back with a second Walker Bean book that I can only describe as more of the same, but longer and even more ambitious: The Unsinkable Walker Bean and the Knights of the Waxing Moon, an adventure at once hectic and transporting, overbusy yet oddly soulful. When I first read it, it drove me a bit nuts, so mazy and bewildering is its plot. When I re-read it, though—well, I think I got it. The world of Walker Bean consists of salty pirate tales (in the Stevenson tradition) blended with high fantasy. It takes place in an odd variation on the known world that mixes real and invented geography, in an unspecified period that feels like a dreamlike rewriting of the nineteenth century. Walker is a shy, bookish boy, frankly a nerd: brilliant, but fragile and sensitive. People treat him as a softy, but he has steel in him; on the other hand, he can be a bit of a pill. Most unwillingly, Walker gets pressed into nautical adventures that carry him far from his home on Winooski Bay and introduce him to supernatural forces and secret histories. The first book concerned a magical skull, two monstrous “sea-witches,” and a seafaring quest, much of it aboard a tricked-out ship called the Jacklight, which could travel over land as well as wave. In that one, Walker was joined in his travels by Shiv, a powder monkey, and Genoa, an intense and mysterious adventuress. They are still together in the new book, and make for a sturdy triad (in a sort of Harry-Ron-Hermione way). Knights of the Waxing Moon shares the spirit of its predecessor, and offers continued treasure-hunting, with many of the same characters (as well as many new ones). But there’s less sailing, now, because the story takes place mainly on the same haunted archipelago where Walker and friends were stranded at the end of the first book: the Mango Islands. Basically, this is a “mysterious island” tale. Something happened on the archipelago long ago, something that still casts a long shadow. Competing treasure-hunters, some much older than they appear, seek a source of power—a magical metal—and again supernatural agents and occult histories are high in the mix. Mistaken identities play a part, as do bemusing visits to the past. Mysterious shadow-beasts that guard the islands add a whiff of Miyazaki: the environment seems neither benign nor malevolent, but sublime and indifferent. As in the first book, the stakes are high, the violence consequential, and the scares properly scary; Walker and friends experience sadness, anxiety, and loss along with ripsnorting adventure. If I faulted the first Walker Bean for getting lost in its unlikely, careening plot, I have to say the same of the second. Plot-wise, Knights is the equivalent of juggling cutlasses and cannonballs—tricky, that is. I confess that on first reading I had trouble following the story’s logic, its links and reversals, its mad, ambitious sprawl and ballooning cast of characters. In fact, I finished my first reading—a breathless, late-night binge—in a knot of frustration. For a moment, I thought of the book as a failure: a dream that had gotten hopelessly blurred en route. Hallucinatory flashbacks, inscrutable clues, magical MacGuffins, and sudden, disorienting setpieces, not to mention the many new characters, make Knights a challenging, even frustrating tangle. Transitions are often abrupt, and essential details and connections are sometimes left for the reader to intuit. The relationships among the characters are not easy to chart: motivations are shaded, and alliances form or fail on the spur of the moment. Doppelgangers and ghosts abound. Our three young heroes are called upon to change, and Genoa in particular goes through a startling self-discovery. So, there’s a lot to take in. A lot. So confounded was I by my first reading that, in defiance of my schedule and good sense, I reread the book immediately—and reread the first book too. The second time around, Knights seemed to click: I grasped a number of hints and foreshadowings, better understood certain transitions, and, in sum, could more easily negotiate the plot-rigging. If on the first pass Knights seemed jumbled, with a hiccoughing rhythm and befuddling climax, on second read the book revealed an insinuating story with elaborately braided details, a designing shape, and knowing callbacks to its predecessor. As a self-standing graphic novel, Knights may seem overdense, or over-egged, but as one leg in a longer journey, a further unveiling of a big, big world, it’s a marvel.  Although Knights spins its own distinctive yarn, it does require readers to know the first book intimately (not for nothing did First Second reprint the first a few weeks ago). It refers back to its forerunner constantly, in ways both obvious and subliminal—and this was part of my problem on first reading, because I needed the first book in front of me in order to follow the second. Some of these callbacks fulfill mysteries teased out in the first book, while others deepen the mystery, or extend the original’s meaning. Knights, in short, asks to be read alongside its predecessor. At the same time, it outdoes the first book for scale and strangeness: for one thing, it’s about a hundred pages longer. Even then, it seems more compressed, with (often) denser layouts and too-small balloon text. Still, it’s an organic outgrowth of the first book. Revisiting the first, I notice that its back matter includes teasing “sketches of book #2,” and sure enough I do see elements that made it into Knights: Renier clearly had some of this second book in mind more than eight years ago. Knights, then, is both a close sequel and yet its own strange animal. The trickiness of the book’s plot may prove a trial for readers. Yet I take some delight in the way Renier refuses to talk down to us. Clearly, he digs a nested, baroque plot. In fact, his approach to story recaps, on a larger scale, the complicated maps, diagrams, and inventions that he so lovingly draws into the book. I like that. Still, I’d say that the plot is too compacted, and its logic a bit too implicit; this 280-page yarn packs in 500 pages’ worth of complication. At times Knights surrenders clarity for momentum, and, like the first book, sprints through transitions and critical moments that rather beg for a long double-take. What’s more, certain details are left dangling--bait for the next sequel, presumably, but maddening. For example, one of the book’s narrators, a crucial source of exposition, is left shadowed and unidentified, and Walker’s unscrupulous father, briefly glimpsed, remains a nagging loose thread. (I dearly hope it won’t take another eight years to tie off that thread.) More than anything, a passion for worldmaking through drawing animates the Walker Bean books, and on that score Knights of the Waxing Moon matches its forerunner. It piles up, graphically, vividly, a surplus of environments and space, creatures and ships, devices and talismans, all rendered with breathless excitement. Renier, as he zooms ahead, leaves behind a trail of small delights: details that pop out upon rereading, to be savored or puzzled over. In fact the galloping momentum of the story and the luxurious world-building are at odds, making the book at once a sprint and a sightseeing tour, a plot-driven adventure and a dungeon master’s guide (oh man, Walker Bean is a role-playing game just waiting to happen). Judged by the standards of tight, Tintin-esque adventure, the book is a failure—it packs in too much stuff to attain that kind of crystalline form—but as a celebration of drawing worlds into being, man, it’s something. Renier and Longstreth once again turn out beautiful pages and spreads, with a loose, feeling line and sumptuous palette; at the same time, Renier tries out new things in layout, pacing, juxtaposition, and braiding. A labor of love, I cannot help but think. Love and feeling are big for Renier. Both Walker Bean books brim with emotion: characters weep, fret, and startle—gulping, gasping, reacting. They sometimes panic. They get on each others’ nerves too, reproving and arguing with one another. They worry for each other. Walker and his cohort, and even the heavies, wear their emotions near the surface, and many scenes are raw with feeling. Even the quietnesses can be supercharged. Take for instance this loaded moment from early on, as Walker, feeling abandoned, starts an angry letter to his beloved Grandpa, but then thinks better of it: Scenes like these show that Renier values not only the pleasures of drawing but also the vital emotive connection between characters and reader. Some of the relationships in Knights are tumultuous—in fact, testing or reaffirming friendship in the face of severe trials is a large part of what the book is about. The sheer feelingness of Walker Bean is a necessary balance to the baroque plotting and ecstatic drawing. Renier cares about his adventurers, and faithful readers will too. Structure-wise, Renier may be aiming for the kind of unfolding epic that Jeff Smith crafted in Bone. Feels like it. But he isn’t working within the same serial format, one that allowed Smith an unhurried pace, a gradual unspooling and deepening of his imagined world. Nor is Renier publishing with the same momentum as, say, Kazu Kibuishi, whose Amulet series has yielded eight roughly 200-page volumes in a decade. The Walker Bean books are different: jam-packed, overstuffed, sort of obsessive. They bespeak, again, a love of drawing and knotty, puzzle-like storytelling. Renier, I think, loves world-building in a way that can barely be corralled into sensible, well-structured volumes (though he does strive mightily after an overarching structure). His penchant for overstuffing recalls, for me, Mark Siegel et al.’s elaborate 5 Worlds series, except it’s less mediated, more personal: not the result of a carefully managed collaboration that subsumes individual quirks, but the result of one artist running wild. And, you know, I kind of love him for that. Readers who loved the sheer outrageous overspill of the first Walker Bean will also dig the second. Me, I’ll reread these books and take pleasure in them, again and again. In this age of well-shaped, well-behaved, and precisely marketed graphic novels for children, Walker Bean is exceptionally weird, hence wonderful. My gosh, I hope for a third volume. And more.... First Second Books provided a review copy of this book.

The Unsinkable Walker Bean. By Aaron Renier. First Second, 2010. ISBN 978-1596434530. 208 pages, softcover, $15.99. Colored by Alec Longstreth. (This review originally ran on the now-defunct Panelists blog in June 2011. I've revived it here and now because a sequel to Walker Bean is promised this fall. Ever the fusspot, I have not been able to avoid the temptation to trim and update, albeit slightly. - CH) Piracy on the high seas—storybook piracy I mean, the kind we know mostly from echoes of Stevenson and Barrie—remains an adaptable, nigh-bottomless genre. The piratical yarn lends itself to the dream of an infinitely explorable world, to lusty romance, oceanic myth, and shivery deep-sea terrors, all of it salted with enough bilge, filth, and real-world cynicism to sell even the flintiest skeptic. The golden age of Caribbean piracy, which even as it happened was a set of facts angling to become a myth, helped redefine the pirating life as radically democratic, an anarchic space of freedom—ironic, since it grew out of colonialism and the Thirty Years’ War. That age bequeathed us a roll call of larger-than-life persons, Calico Jack, Anne Bonny and Mary Reade, Blackbeard, and the rest: real-life opportunists from whence Stevenson distilled his great, demonic “Sea-Cook,” Long John Silver, Treasure Island’s indelible villain. Silver’s slipperiness lives on, I suppose, in Johnny Depp’s Jack Sparrow, ever scheming, ever sidling away to scheme another day. Pirates of the Caribbean reinvigorated the old genre, but with a heaping dose of hypocrisy. For example, in Bruckheimer, Verbinski, and Depp's third Pirates film (2007), the multinational juggernaut that is Disney pits globalization, in the person of the über-capitalistic East India Company, against scrappy piratical “freedom,” represented by Sparrow and his fellow rum-soaked scumbags. Huh? Couched in terms of post-9/11, post-Patriot Act resistance to a neoliberal mercantilist New World Order, that movie of course made shiploads of money. Such irony. So, the myth of the high-seas pirate carries on, its popularity an index of how we feel about the tug o’war between hegemonic authority and the individual will to live and indulge. Cartoonists in particular seem to love pirate tales and other nautical yarns, maybe because such tales make the world feel larger, maybe because they give license for scruffiness and odd character design (think Segar), maybe simply because the high seas invite so much gushing ink. A fair handful of graphic novels from recent times either plunge into the deep sea or sail off to faraway places: Leviathan, That Salty Air, Far Arden, The Littlest Pirate King, Blacklung, Set to Sea, et cetera (I bet readers can name a few others). Aaron Renier’s The Unsinkable Walker Bean (released, what, eight years ago now?) dives into the genre with a hectic, dizzying 200-page story and a surplus of delicious inky craft. Written and drawn by Renier and colored by Alec Longstreth, Bean is a beautiful, odd book aimed squarely at young readers, the first of a promised series that, it seems to me, aims to mix a carefully rigged Tintin-esque plot with the jouncing unpredictability and eccentricity of Joann Sfar, whose organic approach to both plotting and drawing probably provided inspiration. The materials are familiar enough, but the execution is, wow, crazy. The results strike me as imperfect but delightful. Walker Bean (a cartoonist’s surrogate?) is an unlikely pirate: a nervous, sensitive boy prone to doodling and mad invention, slightly pudgy and bespectacled to make him seem an unexpected hero. His emotions are worn near the surface. The plot tests his ingenuity and bravery, offering plenty of swashbuckling and catastrophic violence in the bargain. It’s sometimes bloody and boasts some real scares. Walker’s world looks like a farrago of eighteenth and nineteenth century elements—costume, settings, ships—but frankly it’s unreal, a synthetic alternate world. Per the map on the frontispiece, that world is like a distorted view of ours but bears fanciful names (e.g., Subrosa Sound, the Gulf of Brush Tail, and cities like New Barkhausen and Tapioca) alongside real ones like the Atlantic and Mediterranean. Anachronisms abound, such as a middle class child’s bedroom casually appointed with books. Stops along the way, such as the colorful port of Spithead, teem with diverse character types who lend the storyworld a distinctly postcolonial vibe. The plot, a mad, churning mess, begins with mythical backstory: a child’s bedtime story about the destruction of Atlantis. Then it veers sharply into pure breathless adventure. Young Walker, to save his ailing grandfather, must brave the high seas in order to return a maleficent artifact to its home in a deep ocean trench. That artifact is a skull of pearl formed in the nacreous saliva of two monstrous sea “witches”: huge lobster-like monsters who caused Atlantis’s fall. The skull is itself a character, evil, cackling, and seductive. One glimpse of it can send a person into shock or even death. Walker’s grandfather, an eccentric, bedridden admiral, entreats the boy to dispose of the skull, while Walker’s father, Captain Bean, a vain, greedy fool, plots to sell the skull for maximum profit, egged on by one “Dr. Patches,” a fraud and a fiend. The action, which zigzags unpredictably, includes long stretches on a pirate ship called the Jacklight. There Walker becomes an unwitting crew member, working with a powder monkey named Shiv and a girl named Genoa—an able thief and fighter who more than once nearly kills Walker. That's as close as the book gets to the excitements of courtship. The pearlescent skull is said to be a source of great power, of course, but keeps tempting would-be possessors to their doom (there’s a strong hint here of Tolkien’s one Ring). Donnybrooks and sea battles alternate with creepy scenes of the skull exerting its influence and big, splashy encounters with the horrific witches. Pages vary from minutely gridded exercises to explosive full-bleed spreads. Plot-wise, there are double-crosses, shipwrecks, and weird critters aplenty, a burgeoning cast of supporting players, and moments of tenderness, confusion, and self-realization. Walker, Gen, and Shiv are all well realized. Walker himself becomes the true hero that the title promises. In the end, things are resolved but other things left open, setting up Volume Two. Renier has not worked out his story perfectly. Honestly, I didn’t retain most of the plot details after reading through the first time; the story ran by me at a mile a minute, and I couldn’t catch it. The plot twists confusingly like a snake underfoot, and logical stretches are many; even for a pirate yarn, the book strains belief. At one point, the remains of a smashed ship conveniently drift into port. At another, the Jacklight, having been completely wrecked, is rebuilt and transformed into an overland vehicle (with wheels) in the space of a single day. In short, Renier leans on plot devices that don’t convince. What’s more, the storytelling is at times more exuberant than clear; certain double-takes and surprises confused me. Pacing and story-flow sometimes hiccup. What we’ve got here is a patently rigged plot set in an overstuffed story-world that is still in the process of being worked out. Walker Bean is a generous story, almost risibly full, but sometimes it's hard to believe. Ah, but how it testifies to the love of craft! The book’s colophon describes in detail Renier’s process of drawing and hand-lettering (on good old-fashioned Bristol board) and then the shared process of coloring (where the digital takes over). All tools and techniques are duly described, even razor-work and the use of Wite-out to vary texture. The descriptions are aimed at any reader; no prior knowledge of technique is assumed. It’s as if Renier and Longstreth wanted to let young readers in on their trade secrets. The book’s coloring, it turns out, began collaboratively: Using some old, faded children’s books for inspiration, Aaron and Alec created a custom palette of 75 colors, which are the only colors used in this book. Coloring a big book is easier when one has only a limited number of colors to choose from, and it makes the colors feel very unified. The results do exhibit an aesthetic unity, without disallowing the occasional eruption of tasty graphic shocks. In any case, the blend of line art and color—handiwork and digital—is gorgeous. Renier, if not yet a surefooted storyteller, is a terrific cartoonist. Vigorous brush- and pen-work, lush texturing and atmosphere, dramatic staging, complex yet readable compositions, and even formalist games—all these are in his ambit. Examples are legion. For instance, check out this panel depicting a bumpy ride: Or this much quieter one, depicting a secret hideout: Renier’s commitment to the work and talent for conjuring strange places and characters show in every page—and every page is different. This is first-rate narrative drawing, stuffed with beauty and promise; it takes the gifts shown in Renier’s first book, Spiral-Bound, and boosts them to a new level. Finally and most importantly, Walker Bean has soul. It makes room for emotional complexity. Minor epiphanies and finely observed silences, scattered across the book, make it much more than an opportune potboiler. Behind the book is a thumping heartbeat that testifies to a reckless love of comics and adventure. This is a yarn without a whiff of condescension: mad, high-spirited, and cool. (Volume Two is due this October. Hmm, what difference will eight years make? Also, note that KinderComics will be on summer break between now and Monday, August 20, 2018.

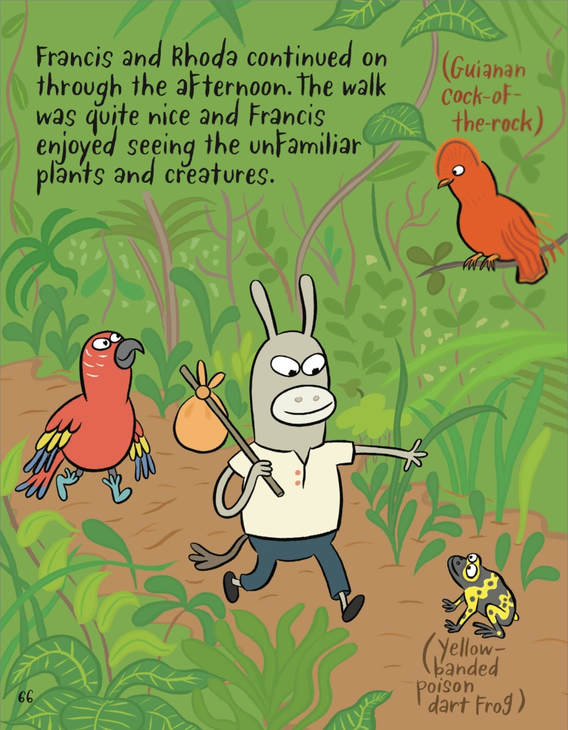

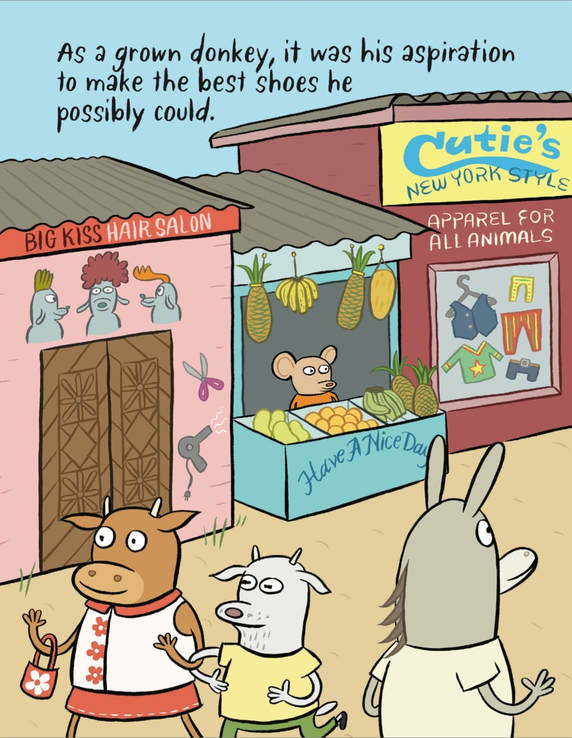

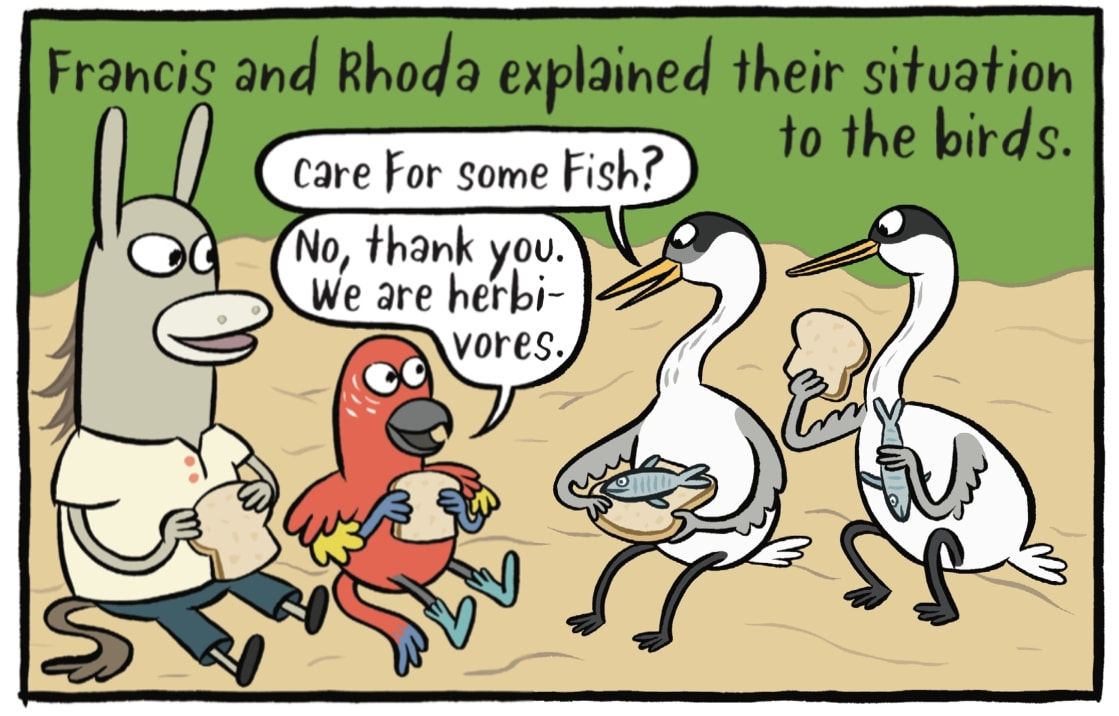

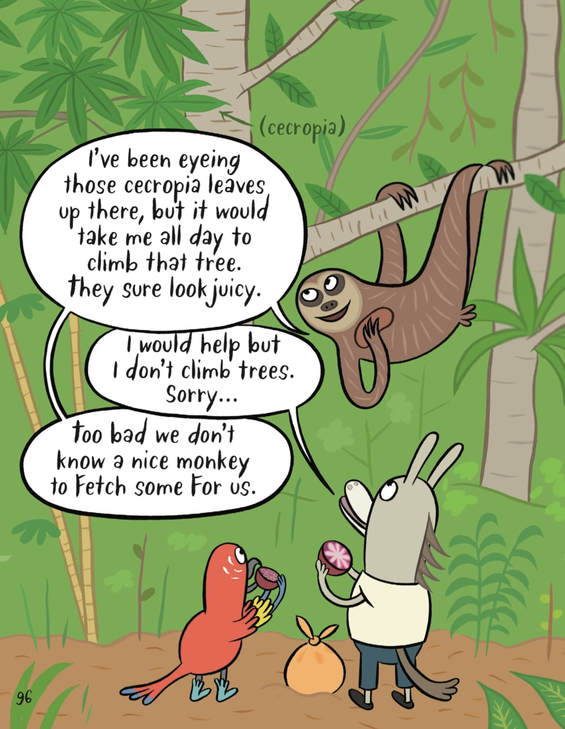

New Shoes. By Sara Varon. First Second Books, March 2018. Hardcover, 208 pages. ISBN 978-1596439207. $17.99. Book design by Danielle Ceccolini and Sara Varon. New Shoes, a genial, unlikely fable, follows a cobbler named Francis who wants more than anything to make the perfect pair of shoes for his favorite singer, a pop star who is coming to his town. To that end, he hopes to enlist his traveling friend, Nigel, to secure the needed supplies—but Nigel, it turns out, is missing. So Francis, aided by another friend, Rhoda, embarks on a quest to get the supplies himself (and find Nigel). The thing is, Francis is a donkey, Nigel is a squirrel monkey, Rhoda is a macaw, and the singer, Miss Manatee, is just that. New Shoes is an animal fable—and not in the purely metaphorical sense of, say, Spiegelman’s Maus, in which human characters wear mask-like animal faces. No, these animals are meant to be animals, even though they’re anthromorphized. Francis, despite wearing clothes and shoes, is emphatically a donkey. Rhoda is a bird (she flies). And so on. In this world, varied animalness is the point. Once again, Sara Varon (Bake Sale, Robot Dreams, Chicken and Cat, Sweaterweather, etc.) has created a funny animal comic that is, yes, funny, but more than that. New Shoes takes place in a tropical world inspired by Guyana. Francis and Rhoda’s quest entails journeying into “the jungle,” i.e. equatorial rainforest, and the book lovingly details Guyanese flora and fauna. Varon gives labels for myriad critters: black curassow, golden-handed tamarin, three-toed sloth, and so on. Ditto for plants: cecropia, philodendron, bromeliad. In other words, the book packs in a lot of zoological and botanical information. More than that, New Shoes implicitly reflects Guyanese culture: an Anglophone Caribbean mix with a complex colonial history and diverse population. Signs in Francis’s village are in English, village buildings are small, colorful, and individual, and Varon’s myriad animal types may stand in, allegorically, for Guyana’s mingling of East Indian, African, Amerindian, and other peoples. Miss Manatee, “the River Queen,” is a calypso singer, and listening to calypso on phonograph records seems to be a cultural constant (record players are an important prop throughout). Varon’s version of Guyana is perhaps utopian but based on direct experience: her husband, John Douglas, former boxer and Olympian (1996), is from Guyana, and her visits there, specifically to the town of Linden, seem to have shaped if not inspired the whole book. The specific cultural and geographical influences of Guyana make New Shoes stand out among Varon’s animal tales—and the characters’ varied animalness implicitly celebrates Guyanese diversity. Thus New Shoes espouses cooperation and harmony-in-difference without dealing explicitly with race, ethnicity, or postcoloniality. This charming fable rests on a complex, if largely implied, cultural foundation. I was struck by the book’s depiction of labor and economy. Even as it extols friendship and community, New Shoes focuses on acts of exchange: goods for goods, goods for work, and work for work. Yet money plays no role; barter and trade are everything. Rhoda agrees to help Francis on his quest in return for a pair of shoes. Francis offers bread to passing herons, who in return counsel him to seek help from some capybara. Later, Francis trades bread to the capybara and some river otters in return for swimming lessons and advice. Later still, he settles a debt with Harriet, a jaguar, by offering her his guidebook to rainforest animals, and then the two make a further exchange: some of Harriet’s plants, and advice on how to take care of them, in return for a pair of Francis’s shoes. While the book also depicts acts of spontaneous, uncompensated kindness—say, a neighbor helping a neighbor—much of its action involves establishing reciprocity and trust through barter. Tellingly, these exchanges are not merely economic but also build goodwill and community. If some characters seem altruistic, others, by contrast, appear self-interested—yet all of them come together civilly through the act of trading. What’s more, the worst offense in the book turns out to be thievery, when a character decides to take something for nothing rather than making an honest trade. Varon’s utopia, then, is not without practical considerations of trade and work, but couches those in terms of communal ethos rather than capital. New Shoes could spark some fascinating exchanges with young readers about use value, exchange value, and perhaps even alternatives to commodity capitalism! Varon’s work has a distinctive charm. Her stories, as New Shoes amply demonstrates, tend to be about not only moving the plot forward but also taking an interest in the world, imparting information about geography, culture, or beloved pastimes. They represent the work and the pleasure of learning. At the same time, Varon uses animals and other “nonhuman” characters to convey feelings of friendship, love, and loss (most piercingly, I think, in her breakthrough book Robot Dreams). Along the way, she scatters moments of droll, deadpan humor: Varon's telltale graphic style is very readable. Her character designs are distinct and unmistakable; every character looks different from every other one (and I can see some influences she has cited, including Jay Ward and William Steig). The figures are clean and shadowless, yet outlined by robust brush-inking. Her bright, unshaded pages boast discrete forms and solid, eye-popping colors, yet also a complex mixing of hues (as in the varied shades of green that make up New Shoes’s rainforest). Inked on Bristol board but then colored in Photoshop (as is Varon's SOP), New Shoes happily blends old-school and digital methods, combining springy linework with subtle coloring. Layout-wise, Varon alternates between framed and unframed images, favoring big, open spreads and full bleeds. Often, single images take up a page or spread; alternately, Varon may go for a page of two or three (or, very rarely, four) panels. Clarity and momentum are all, and New Shoes fairly carries the reader along. Sara Varon has become one of First Second’s signature authors. I had the privilege of interviewing her, back in 2009, at the International Comic Arts Forum in Chicago, and it has been a pleasure to see more and more of her work—work that explores friendship and community for the benefit of young and old readers alike. New Shoes charmed me right off, but keeps growing in my estimation as I think about it—another delightful, subtle, low-key triumph. First Second provided a review copy of this book.

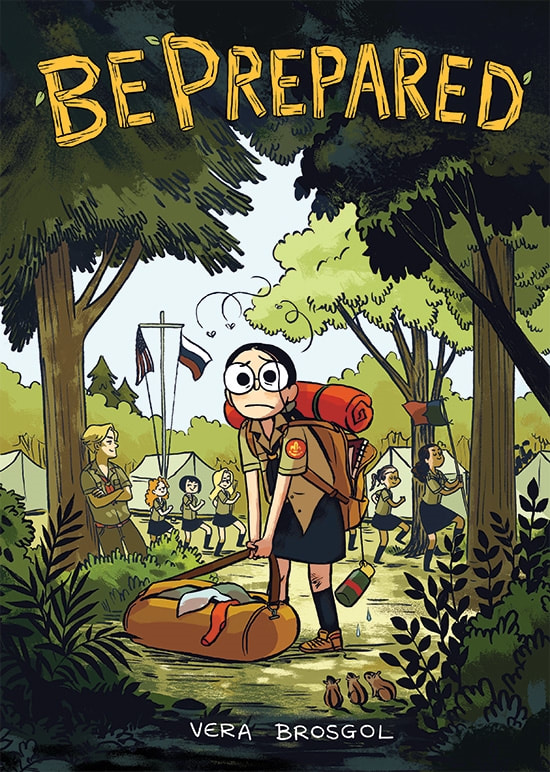

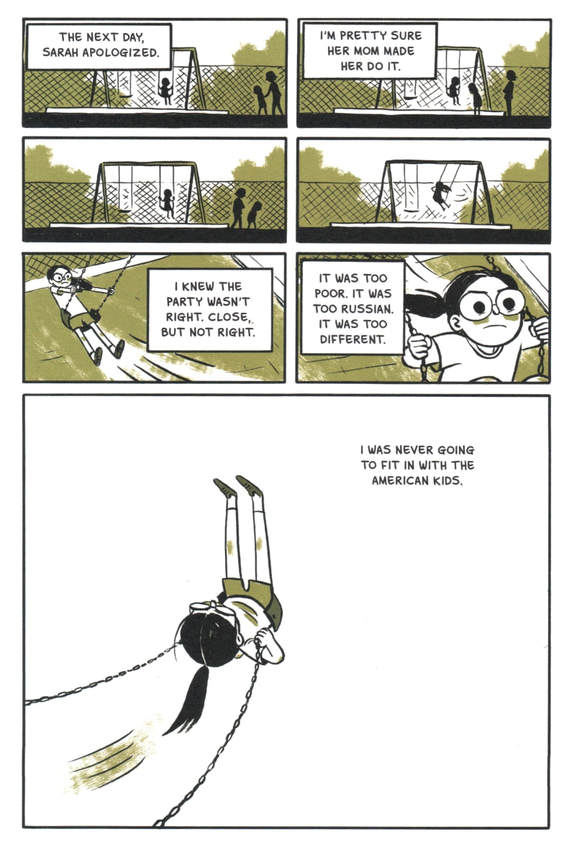

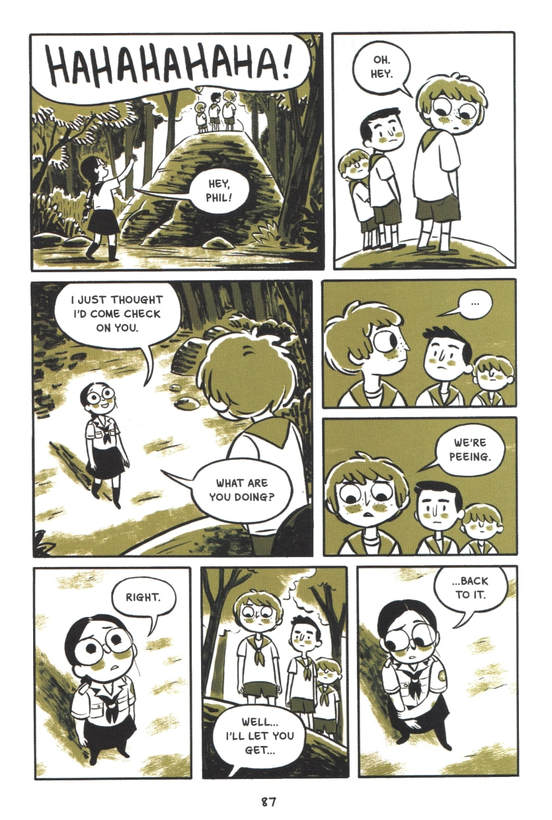

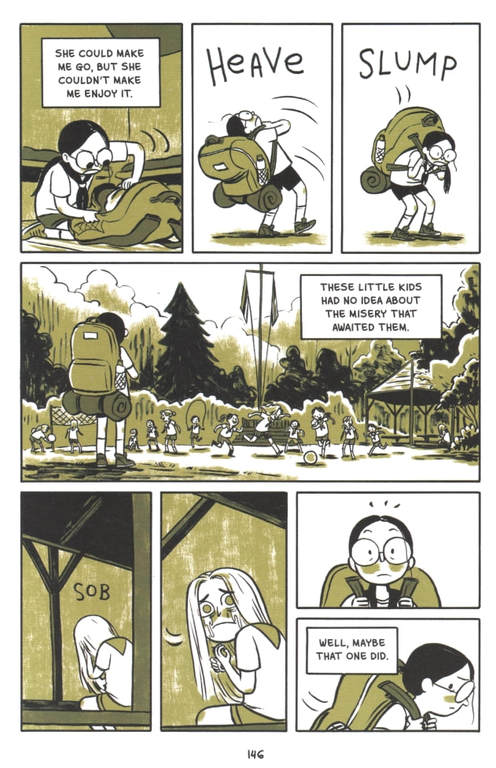

Be Prepared. By Vera Brosgol. Color by Alec Longstreth. First Second Books, April 2018. 256 pages. Hardcover, ISBN 978-1626724440, $22.99. Softcover, ISBN 978-1626724457, $12.99. Book design by Danielle Ceccolini and Rob Steen. About seven years ago, animator and storyboard artist Vera Brosgol entered the world of graphic novels with a walloping big success: Anya's Ghost, a supernatural fantasy rooted in the experience of being a Russian immigrant girl struggling to fit into American life. Brosgol knew this struggle firsthand, having moved from Russia to the US at age five. Anya's Ghost changed Brosgol's life: rapturously reviewed, the book went on to win Eisner, Harvey, and Cybil Awards. Its theme of trying to disavow one's cultural roots resonated with Gene Luen Yang's epochal American Born Chinese, which had been published some five years earlier (both were published by First Second). The two books drew upon popular genres—myth fantasy, superheroes, ghost stories—to fashion nervy fables of complex and ambivalent identity. In that sense, Anya's Ghost appears to have struck a nerve. Now Brosgol, having also authored a Caldecott Honored picture book (2016's Leave Me Alone!), has just released her second graphic novel: the autobiographical Be Prepared, in which a nine-year-old Vera, again a self-conscious Russian immigré, goes to summer camp. Be Prepared is in the same vein of comic memoir as Raina Telgemeier's hugely popular Smile (2010) and Sisters (2014), and indeed the book is being promoted in that light (and has been blurbed by Telgemeier herself). Thematically, however, it pairs with Anya's Ghost, as it mines Brosgol's experience as an immigrant to tell another story of the struggle for identity. This time, though, the story happens in the company of many other Russian kids, in the context of a Russian immersion camp with Orthodox roots. From this intriguingly specific setting, Be Prepared builds a book that turns out to be, tonally, quite different from Anya's Ghost, yet is just as wonderful. Be Prepared begins with, once again, the discomfort, or even humiliation, of being a markedly Russian girl in a suburban American world dominated by unmarked middle-class Whiteness. Yet, whereas Anya's Ghost centers on a somewhat sullen and alienated adolescent, and thus tacks in the direction of Young Adult fiction, Be Prepared's Vera is naive, hopeful, and intimidated by teens. Yet she is worldly-wise enough to know that she sticks out like a sore thumb, that she is too ethnic, "too different," to fit easily into her town and school in Upstate New York. Indeed Vera is painfully aware of being "too poor" and "too Russian" to blend in with her schoolmates. However, whereas Brosgol's Anya seemed determined to shed her Russianness, Vera thrills to the prospect of attending an all-Russian camp in the New England woods. Most of her schoolmates go away to camp every summer, leaving Vera adrift and bored, but when she learns of a camp where "everyone would be Russian like me," she dares to hope that it will ease the pain of being different. "I had to go," she says. "I had to go." Vera and her little brother Phil do go, and here is where Be Prepared takes off, as it conjures the distinctive setting of a Russian scouting camp, dotted with Russian signage and Orthodox icons. The setting appears to be (guesswork here) based on a real-life camp run by the Organization of Russian Young Pathfinders (Организация Российских Юных Разведчиков, or ORYuR) or some similar Russian Scouting in Exile group. It's all about being Russian, all the time. Camp songs are sung in Russian; Russian speech (a constant) is represented by English within brackets; and each week the boys and girls compete in a capture-the-flag contest called napadenya (attack). The problem is, camp sucks. Vera's hopes of fitting in are dashed: she is placed with older girls who patronize her, her Russian is too tentative, and roughing it freaks her out. Too late: she is committed, and has to stay. Thence comes much of the book's poignancy and humor. I appreciate the frankness, and sometimes rawness, of Brosgol's humor. As she did in Anya's Ghost, here again she tests what a young reader's book can get away with. The young campers of Be Prepared are emphatically people with bodies, and much of the book's comedy stems from putting those bodies under duress, as happens when you go camping. Bites, stings, toileting, and adolescent growing pains are all played for laughs, and many of the gags involve visits to the dreaded latrine. There's some pain behind the laughs. Brosgol's humor has a salty matter-of-factness that will likely ring true for just about anyone who's ever been to summer camp, as in this sequence where Vera pays her brother a rare visit: Or this mortifying moment between Vera and her two tent-mates: There is more to Be Prepared than these moments of rough humor and embarrassment. There's testing, growth, and self-recognition. There's struggle and loneliness, but ultimately affirmation (though thankfully no platitudes). And, man oh man, is there great cartooning. Be Prepared is a delight because Brosgol is an ace artist with a gift for designing characters, pacing stories, and building pages. The characters, as one might expect of a skilled animator, are clearly tagged, i.e. graphically distinct. Young Vera herself, moonfaced, with coke-bottle glasses and big, dark dots for eyes, is unmistakable: a live antenna of a character, veering from joy to misery, anticipation to disappointment. Brosgol cartoons her (that is to say herself) with comic brio, ruthless insight, and, yes, empathy. Other characters are vivid types, from Vera's teenage tent-mates, both named Sasha, to the cocky alpha male they compete over, to Vera's camp counselor, at first harried and remote, later sympathetic. Brosgol steers these characters and more through shifting moods, reversals, sometimes betrayals, and oh so many moments of cringing social awkwardness. Further, Brosgol's way with a page, her rhythmic sense of how to make each page build to a payoff, gag, shock, or suspenseful breath, is exhilarating. Her dynamically gridded pages, avoiding tedium but seldom grandstanding, serve the elastic rhythms of the storytelling, and wow does the story move. Though her methods are entirely traditional and convention-bound, Brosgol's sheer fluency is something to behold. Be Prepared is visually masterful, from exacting body language, to precisely observed physical business (camping, hiking, sneaking around), to the rare moments of, whew, calm. Much credit must go to the gorgeously worked surfaces of the pages, completed by the sumptuous coloring of Alec Longstreth, who works wonders with a riotous mix of greens (my scans, here, are too dull to do his work justice). For a strictly "two-color" book, green and black, Be Prepared is replete and ravishing, an opulent outlay of textures. Be Prepared is beautiful, gutsy, and funny. Granted, it does not have the Gothic horror of Anya's Ghost, and does not resonate quite so unnervingly. Rather, it's a breeze of a book, a charming, vivid comedy. Yet a closer look reveals moments of trouble and complexity that, as usual for Brosgol, are not tidily resolved but instead allowed to hang, unfinished and provoking. There are still doses of painful honesty behind the bright, emphatic delivery—and the ending somewhat short-circuits the expected lessons of growth and acceptance, to my delight. If Be Prepared isn't nominated for several awards next year, I'll eat my hat. Need I say that it comes highly recommended?

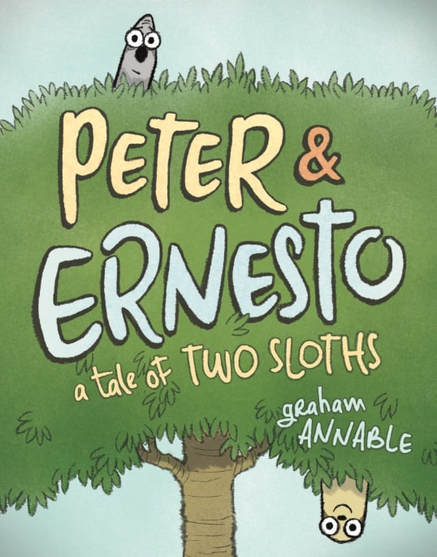

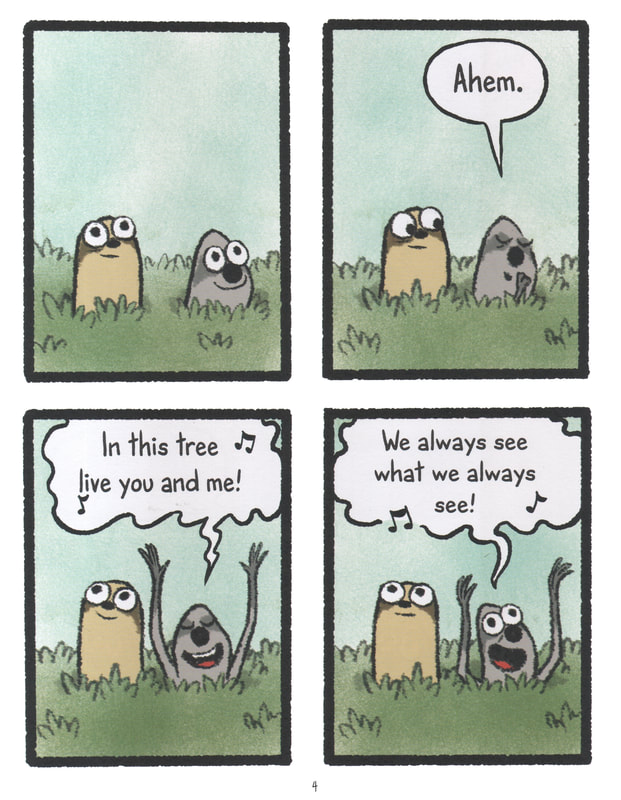

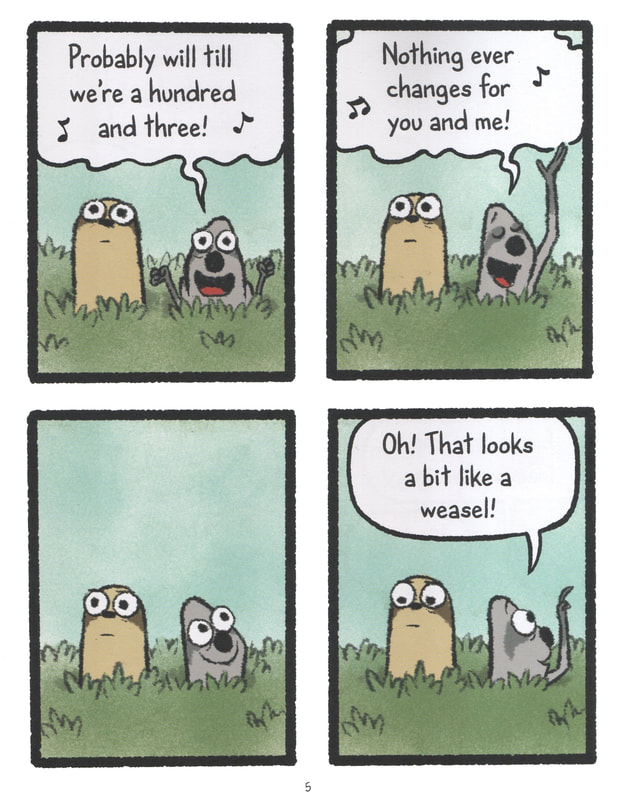

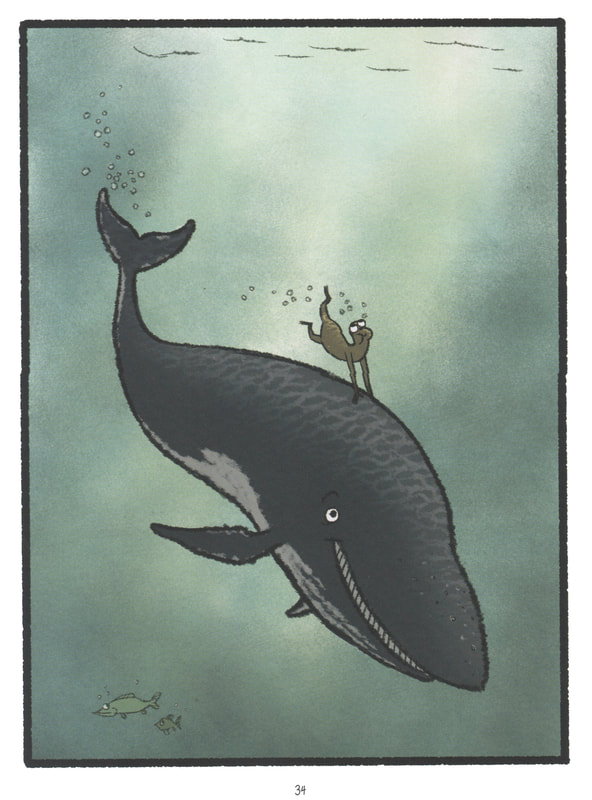

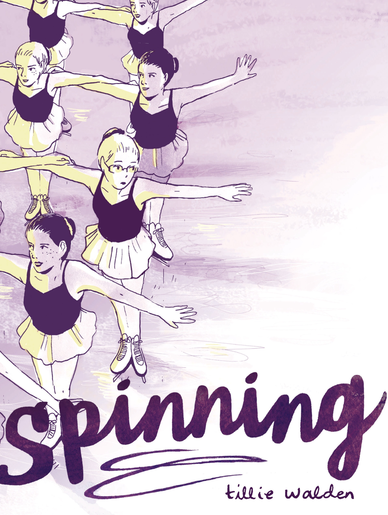

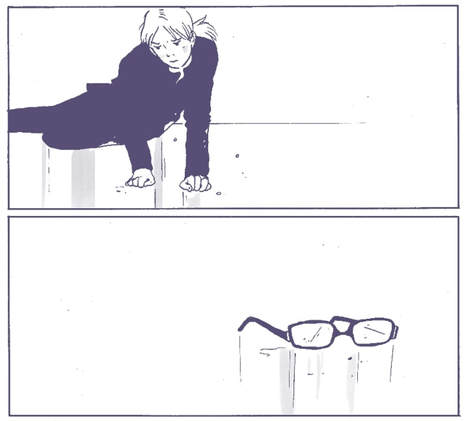

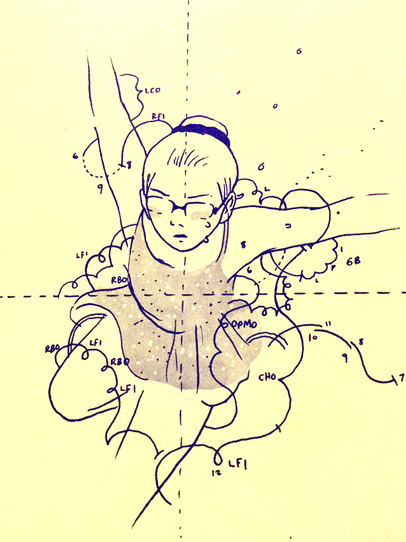

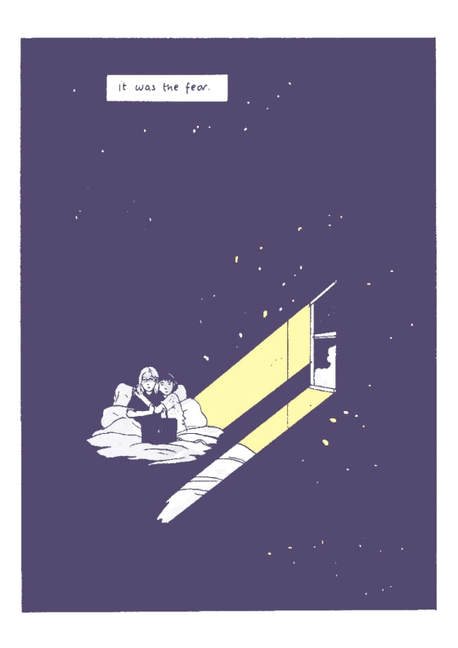

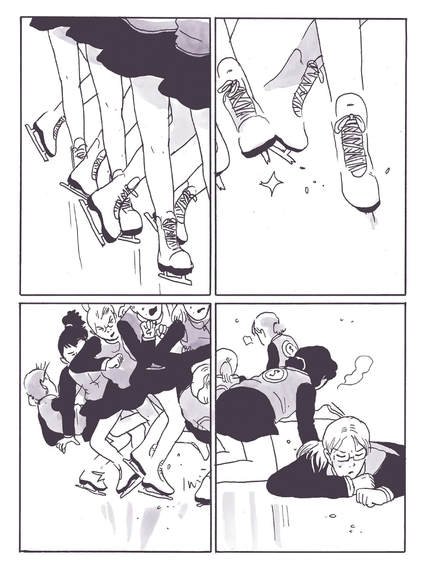

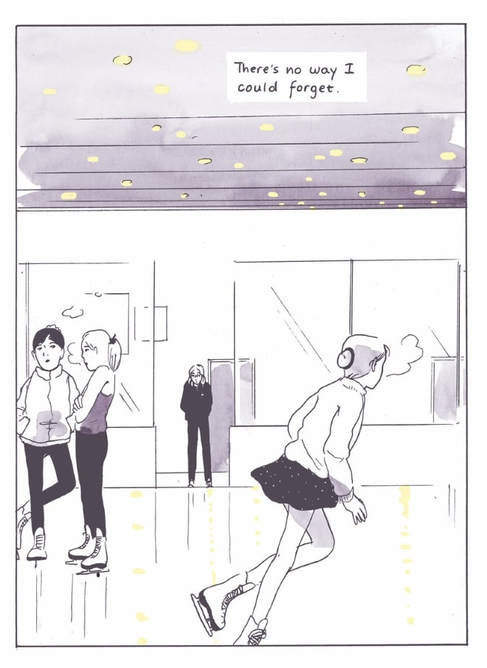

Peter & Ernesto: A Tale of Two Sloths. By Graham Annable. First Second, 2018. ISBN 978-1626725614. $17.99, 128 pages. Book design by Danielle Ceccolini. Cartoonist, animator, and director Graham Annable (The Book of Grickle, Puzzle Agent, The Grickle Channel on YouTube, etc.) is a wickedly smart humorist working his own distinctive vein of anxious, twitchy, sometimes disturbing comics, films, and games. At times his work is very dark: some readers may remember his tale "Burden" (Papercutter #3, Fall 2006), reprinted in The Best American Comics 2008 (edited by Lynda Barry). Sometimes his work is more eager to please, but still uneasy; I'd place the Laika film The Boxtrolls, which he co-directed, in that category. The various Grickle projects are pure Annable, a window onto his sensibility: nervous humor, odd beats, and bug-eyed characters who look a lot like Annable's own thumbnail image from Twitter: Peter & Ernesto is Annable's first children's book. It's terrific and strange: a buddy story in which the two buddies are mostly separated. One, Ernesto, seeks adventure and new experience. The other, Peter, craves security and sameness. They happen to be sloths. Their story begins in a treetop, as together the two of them indulge in the happy pastime of reading the shapes of clouds: a friendly idyll. Right away, though, the two diverge. As Peter joyfully basks in the unchanging familiarity of their lives, Ernesto begins to look—well, restless. And almost worried. As if the smallness of their shared world is closing in on him. The scene is tender, anxious, and funny, like the book as a whole: From there, Ernesto takes off to see the world, going where Peter dare not follow. But Peter’s concern for Ernesto overtakes his fear, and he sets out after his friend as if to protect him from the wide world—even though Peter can hardly bear to face that world himself. For much of the book, then, Peter follows belatedly behind Ernesto, so that the reader re-experiences places they have already visited, pages earlier—but it’s much different the second time around. As Ernesto revels in the unexpected thrills of his frankly improvised journey, Peter encounters the same scenes, and hurdles, with fear and trembling. There’s a lot of loopy business en route, much of it involving other comic animals, before a neat, affirming close. Annable’s comic timing his great, he mines Peter’s anxious qualms for tender, empathetic humor, and the world comes out seeming like a grand place. Implicitly, Peter & Ernesto is an odd-couple narrative for both brave, venturesome kids and diffident, anxious ones. There are a lot of children’s stories like this: depictions of sometimes contrasting and yet loyal friends. I hear an echo of Arnold Lobel’s Frog and Toad books here (Frog and Toad Are Friends and its four sequels, 1970-1979), and Annable has said that they were indeed an influence. Sesame Street's Ernie and Bert come to mind too. What I particularly like about Peter & Ernesto is its deft cartooning and comic timing—and the way Annable, a poet of nervousness, gets me to sympathize with both the world-conquering Ernesto and especially the timorous, uncertain Peter. Drawn in Photoshop with customized brushes, Peter & Ernesto boasts a ragged, trembling line and organic look. It is beautifully and subtly colored: Peter and Ernesto live in a great green and blue world. Yet it’s Annable’s shivery lines and coarse textures that set the book apart—those, and his animator’s knack for distinctive and expressive character design. Peter and Ernesto are very easy to tell apart. As for the other players—monkeys, dromedary, tapir, whale, and so on—they are great cartoon characters, all. Annable keeps things schematic and clear, with page layouts that vary discreetly among full-page panels and two, three, and four-panel grids (oh, but there's one glorious exception that you'll have to see for yourself). Every panel is a rectangle bounded by the same thick, ragged black line, but this sameness grounds the book and brings it to life, rhythmically. All parts work together. In short, Peter & Ernesto is a little triumph of spare, funny cartooning, and comes highly recommended. A sequel is coming. That's good news. First Second provided a review copy of this book. Spinning. By Tillie Walden. First Second, 2017. ISBN 978-1626729407. $17.99, 400 pages. Nominated for a 2018 Excellence in Graphic Literature Award. The feeling of waiting curbside for a ride in the predawn cold, watching headlights sweep through the darkness. Of peering out windows on sleepy car rides. Of early-morning arrival at the ice rink. Of locker rooms, benches, and earbuds, of lacing up your ice skates, everyone in their own little orbit, quietly, tensely readying themselves. Of being the new girl, of being sized up to see if you are “a threat.” Of skating across the ice, jumping and falling, your eyeglasses flinging off and away. The feeling of a teacher’s hands on your shoulders, helping you on with your jacket, and the inward recognition that you are gay. Of sidelong glances in a classroom, “dizzy” with longing. Of walking in a crowd of girls, talking about Twilight (Edward or Jacob?), while hiding who you are. Of playing “never have I ever” with the girls while hiding who you are. Of passing. Of trying to recreate, as a skater, with your body, the “tiny graphs and charts,” the “intricate patterns and minute details,” of an instruction book. Of desperately holding hands during a synchro skating routine. Even as the speed is “ripping them apart.” Holding on for dear life. Of friendship as a lifeline. As rivalry and sympathy intermingled. The feeling of being judged, as your teammate speeds up to walk a few paces ahead of you. Of winning and losing, of exulting in first place and weeping when you lose. Of knowing that you cannot always be the one that wins. The tears of your competitors, and your own. The dread of the school bully, rendered faceless in memory but still so powerfully there. Your hands nervously playing in your lap, or gripping your knees. Your teacher questioning you. The feeling of falling asleep next to your brother by the light of a laptop screen. Of crying from the makeup in your eyes. Of pulling a blanket up over your head. The sight of the girl you like stretching, and quietly smiling at you. The feeling of being alone with her. Of love, bounded by fear. Of kissing: I didn’t know it would feel like that. Of capering in a hotel room, alone, free from anyone’s judgment. Gazing into your reflection in the surface of a vending machine. The felt “eternity” of a three-minute skating routine. Feet in the air, in mid-jump. Stares and glances. Stares and glances. Girlhood as competitive arena. The feeling of being tested, and failing. Of being alone in a closed room with a tutor who treats you as a thing. The memory of his hand. The feeling of coming out, in a broad, silent room crossed by a slanting beam of sunlight, your mother huddled, tense. Of coming out to your music teacher, in a loving embrace. The sensation of drawing. Of time collapsed into drawing. Of a skate remembered as a nervous, tight grid of panels. Of moves and thoughts flickering. Of falling. Oh my god / my coach is looking at me / the audience shit / the judges The sight of oncoming headlights like round staring eyes. The memory of his hand. Of quitting skating. Walking away.

Driving away, crying. Of returning to the rink, once more, just to prove that you can leave. (There’s no way I could forget.) For all these experiences, and many more--so finely observed, so precisely caught, in a style at once tense and graceful, minimal yet conveying every telling detail, rigorous and yet so light and free—for all this, Tillie Walden’s memoir Spinning is an unforgettable comic, the kind that gets inside your mind and heart. I cannot recommend it highly enough. |

Archives

April 2022

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed