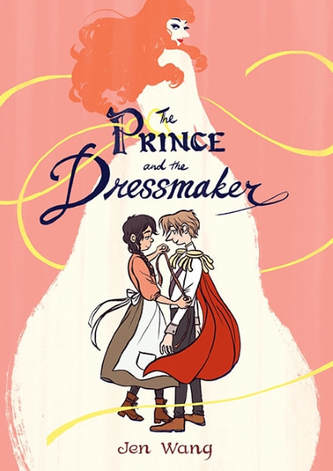

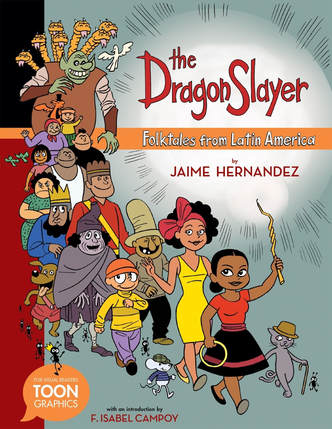

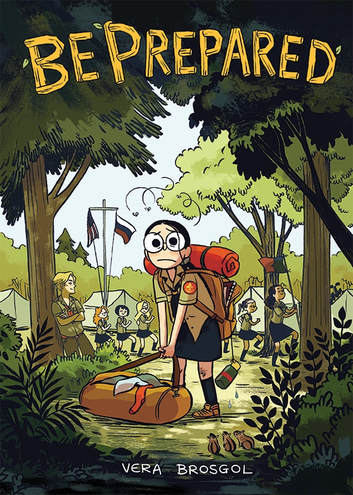

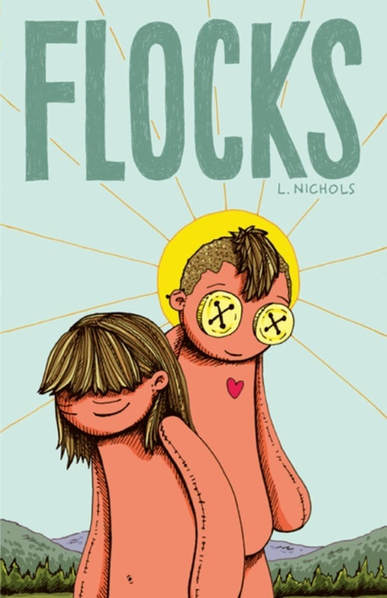

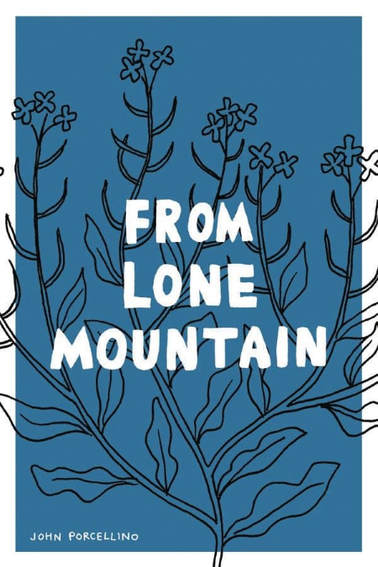

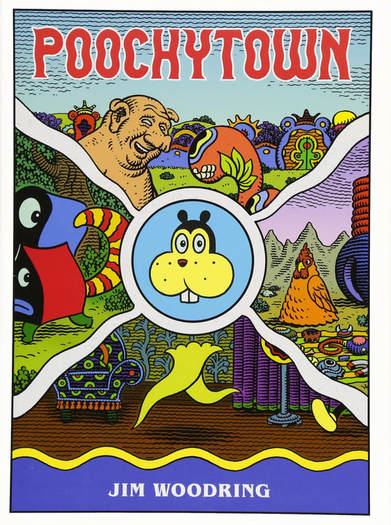

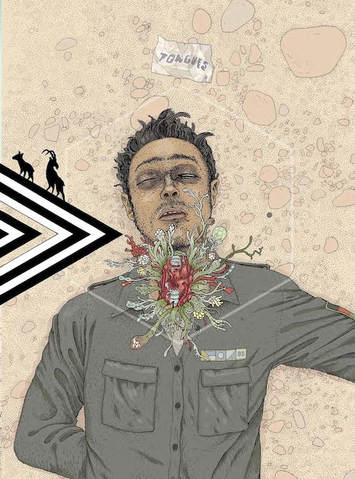

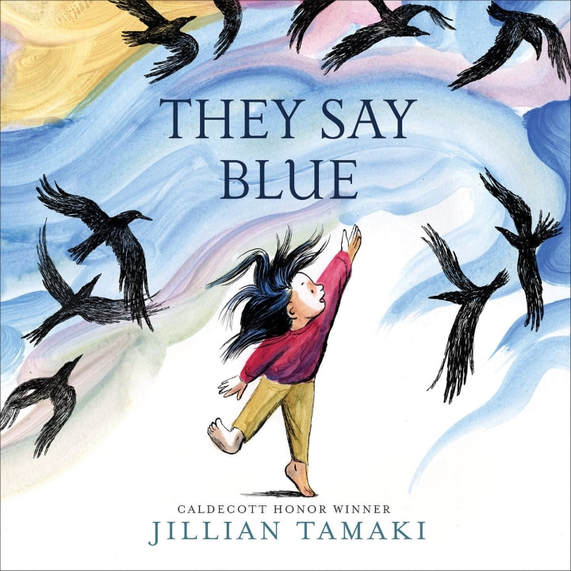

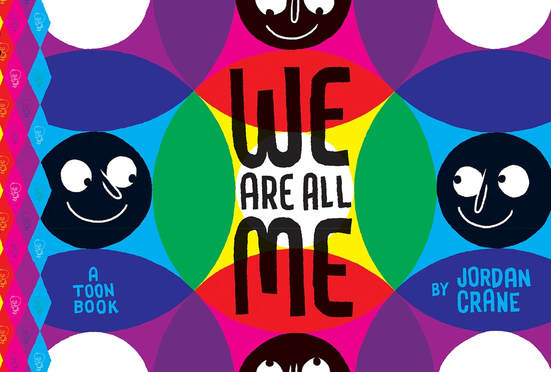

Tempus Fugit Dept.:What follows is a rundown of English-language comics newly published in North America in 2018 that have left strong impressions on me — but it is NOT intended as a "best of 2018" list. Frankly, it's too quirky, too patchy and selective, to qualify as a professional survey of the field's best. It testifies to a comics-reading life hemmed in by other obligations, and by the amount of time I've spent rereading, teaching, and writing about titles from before 2018. For example, this list is manga-less, testifying to the fact that I tend to binge-read manga seasonally, guided by nudges from my daughter Nami Kitsune Hatfield (and those binges usually consist of older titles; my time lag on manga is considerable). Likewise, this list is Eurocomics-free. These are sad omissions, but a fair take on how my year has gone. Also missing are webcomics, as I don't yet have a steady webcomics-reading habit or a firm sense of that huge, and vital, field. That said, I stand by the following list, which contains, IMO, some of the best print comics published in North America this past year. They are not all young readers' comics, i.e., not all books I'd review for this blog — but those I have reviewed on KinderComics are mostly up top. (Doing KinderComics has certainly shifted the balance of my comics-reading toward kids' titles.) Two picture books round out the list, at the bottom. The Prince and the Dressmaker, by Jen Wang (First Second Books). A gorgeously drawn, progressive, Belle Époque fairy tale about couture, gender, desire, hiding out, and coming out. Its nuanced artwork, tender and expressive, is charged with complex, unspoken feeling. I dig both the aesthetic loveliness and generous spirit of this graphic novel, which is positively swoonworthy. KinderComics reviewed this on March 14. The Dragon Slayer: Folktales from Latin America, by Jaime Hernandez (TOON). The first children's book by the great Xaime (see Love & Rockets, below) is a treasure: a set of three stories that have the off-kilter, arbitrary, but oh-so-perfect logic of traditional tales. These are droll and lovely comics, delivered with the author's trademark classicism, clarity, and verve. Just a plain delight. In a better world, folk and fairy tale comics like these would be reaching millions of young readers every month, in affordable comic book form (I dream of a more culturally diverse Fairy Tale Parade for the 21st century). May there be more of this kind of work from Xaime! KinderComics reviewed this on April 5. Be Prepared, by Vera Brosgol (First Second). The author of Anya's Ghost switches gears, from children's Gothic to a Raina-style memoir of summer camp. An ambivalent, though affirming, tale of cultural heritage, tween awkwardness, and hard lessons. Sharp, funny, and refreshingly unsentimental, with killer cartooning and comic timing. I like the fact that Brosgol sometimes lets her kid protagonists be jerks and that she indulges in bodily and occasionally raw humor. KinderComics reviewed this on May 21. The Cardboard Kingdom, by Chad Sell et al. (Knopf/Random House). A paean to creativity and community: a diverse bunch of kids get together, make stuff, and transform their suburban neighborhood into one nonstop live action role-playing campaign: a shared game of let's-pretend, populated with stalwart “heroes” and gleeful “villains.” Remarkably, this novel follows almost twenty distinct characters (each chapter focuses on a different character or group, and each is co-written by Sell and another creator) and yet it all hangs together, building to a big, punchy climax. Along the way, many of the characters defy societal norms — especially around gender and sexuality — and Sell and co. build a utopian vision of community that happily incorporates and celebrates difference. I’ve admired this book from the first, but when I reviewed it back on May 28, I did complain a bit, saying that the story seemed a bit too perfect, too quickly and neatly resolved, and that the book telegraphed its punches too obviously. However, having reread and taught The Cardboard Kingdom this past week, I’ve come to see it as a remarkable achievement, and I expect that it’s going to be a watershed for middle-grade graphic novels. Sell’s cartooning, lively and eminently readable, is the unifying factor, and should not be underrated (he hides his painstaking work in plain sight: everything seems effortless). I don’t think I’ve ever seen a better treatment of what superheroes can mean for young children. (What is the “Gargoyle” chapter, if not the story of a young Batman fan?) On a Sunbeam, by Tillie Walden (First Second). Walden has great artistic courage, and a genius for comics. Like Jillian Tamaki and Eleanor Davis, she shows such skill and daring that she leaves me gobsmacked. Collecting and revising her epic webcomic, this graphic novel could serve as Exhibit A of her dumbfounding excellence. It’s a tale of love and community, exile and rescue. In a boarding school. In space. A first-class genre-masher, it works as both a heartfelt queer romance and a caroming space opera. Walden's graceful, economical art conjures up a fantastical world and a found family of diverse, shaded characters. The work is generous, yet dares you to take it on its own terms. I read this in one breathless, late-night sitting, wow, and reviewed it on October 26. Book of the Year? Sabrina, by Nick Drnaso (Drawn and Quarterly). Not a children’s book. Chill and frightening, but oh so terribly human and believable. Here's what I had to say about this timely and upsetting graphic novel on its initial release: "A tense, quietly devastating clockwork of a book—drenched in unease and punctuated by moments of muted terror. A study of misinformation, fake news, post-9/11 paranoia, and epistemological doubt—and, more importantly, how it feels to live with these things, on an everyday human level. Sterile, clip-art like drawings, deadpan, seemingly emotionless, and inscrutable, become, as you read in deeper, perfect conveyors of dread." I stand by that: reading this book was an unsettling experience that stayed in my head, haunting me, nagging me, for days. Why Art?, by Eleanor Davis (Fantagraphics). A satirical allegory of sorts, smart and stinging as a whip, but humane and thrilling too. It starts by poking fun at the fatuous self-regard of artists, but then upshifts into a poignant, confounding fable about how much (too much?) we demand of art in catastrophic times. Davis is one of the best comics artists today, an impeccable cartoonist and designer, also a great writer. Again and again, she turns mockery into sympathy, unsettles settled opinions, and overturns smug knowingness in favor of a more complex, and earned, humanity. Small book, big yield. I reviewed this at Extra Inks (the Inks and Comics Studies Society blog) on March 24. Girl Town, by Carolyn Nowak (Top Shelf). I discovered Nowak through her erotic minicomic, No Better Words (which is great — see my mini-review here). Soon after, Top Shelf released this, her first big collection, which includes the celebrated story "Diana's Electric Tongue" and other tales. Aptly named, Girl Town is a queer-positive anthology of young woman-centered tales that evoke uncertain, often unspoken feelings (it could be considered Young Adult fiction, though I don’t think it’s YA by design). The stories are perhaps uneven, some more finished-seeming than others, but every one of them hits home. The best of them are great. Nowak does tenderness and feeling so well; you can feel the desire welling up in her characters. Her cartooning and timing: flawless. I bet we’ll be raving about Carolyn Novak years from now. Flocks, by L. Nichols (Secret Acres). This memoir about growing up queer in a fundamentalist community depicts its protagonist as a rag doll, surrounded by characters rendered in more conventional fashion. At the same time, the pages are full of scientific notation, as if guilt, fear, and alienation could be drawn out as a physics problem — aesthetically, I’ve never seen another comic like it. Flocks does that thing that I long for comics to do: communicate feeling through a complex visual language of its own. Remarkably, this story about how to find your identity within and between your “flocks” (your communities, or social worlds) avoids rancor in favor of a comprehensive love and understanding, even as it criticizes and ultimately rejects fundamentalism and its protagonist literally transitions into a new life. A beautiful, affirming book, deeply personal, and a compelling addition to the growing comics literature on trans experience. I wrote about this briefly on KinderComics, on October 9. From Lone Mountain, by John Porcellino (Drawn and Quarterly). John P is a national treasure. From Lone Mountain is an exquisite collection of four to five years’ (seven issues’) worth of comics and stories from his indispensable zine King-Cat. Tender, heartbreaking remembrances of everyday life and of life-changing loss and struggle, all distilled down into John P’s crystalline, oh-so-spare, Zen-minimalist style. A record of a hard passage in the life of one of America’s greatest cartoonists — and that rare thing, a truly moving comic that brings tears to my eyes. I reviewed this wonderful book for The Comics Journal, back in March. Poochytown, by Jim Woodring (Fantagraphics). Woodring returns to the Surreal, dreamlike world of Frank (bucktoothed zoomorph of uncertain species) to rewrite, or unwrite, an earlier episode. It's as if the jury has been instructed to disregard earlier testimony (but who can ever forget such testimony?). The result feels like having a recurrent dream with variations, or like winding back to the start of something that seems oddly familiar but then fails to stick to what you expected. No matter: the wordless misadventures (joys, sufferings, weird trips) of Frank and company are among the most hypnotic comics I know, and also the most alarming, as the characters' surface cuteness often gives way to amoral selfishness, self-defeating foolishness, and even downright cruelty (these are adult books). Behind the mask of cuteness lies a loving terror at the mysteries of life. This graphic novel is an especially loaded example. In short, Poochytown (rendered as ever in the mesmerizing Woodring Wavy Line) is strange and delightful. Whenever I finish a Woodring book, I feel as if I've come back from a journey to a distinct and unnerving place — one I always want to revisit. In addition to the above self-contained graphic books, I have, of course, continued following a number of comic book (i.e. pamphlet or floppy) serials this year. Most, but not all, have been direct-market series in the traditional sense. Here are the four that have impressed me most. None began this year, and so none is quite new, but of all the floppies I've tracked, these have been the most meaningful for me: Tongues #2, by Anders Nilsen (No Miracles Press). It might not be quite right to call this a "floppy" serial, but it is literally that, i.e. a saddle-stitched comic book periodical (or sporadical). Really, it's as lavish as any of the books listed above: a real art object. It's also narratively dense and, frankly, mind-boggling. At once a fable, myth fantasy, puzzle, and brutal take on our brutal world, Tongues consists of multiple intertwining stories that promise some kind of awful shared meaning. Nilsen uses the fantastic to probe and trouble, never to back away from what's hard. I have no idea where this is going, but each new issue startles and then haunts me. And its beautiful, oversized format is narratively meaningful: not just sumptuous, not just lavishly drawn and printed, but insinuating, teasingly coded, designed down to the last significant detail. These are masterful comics, eerie and destabilizing in the best way. (I reviewed the first issue of Tongues for Extra Inks on August 1.) Frontier #17, by Lauren Weinstein (Youth in Decline). Like Tongues, Frontier might be considered a kind of "art floppy," one that few comic book stores will carry. That's too bad, because this quarterly anthology is outstanding. It devotes each issue to a single artist, and there have been some wonderful ones: Jillian Tamaki, Eleanor Davis, Rebecca Sugar, Emily Carroll, Michael DeForge, and more. Honestly, every issue is strong. This issue, by Lauren Weinstein, consists of "Mother's Walk," a memoir of childbearing and parenting, in fact the story of her second child’s birth. Gutsy, explicit, tender, alarming, and funny, it’s a wonderfully frank comic about a dimension of life too often soft-pedaled, sentimentalized, and mystified. Weinstein paints and cartoons in a way that's deliriously free and unconventional. As soon as I read this book, I decided to add it to the reading list in my comics class next semester. Weinstein says she has more stories to tell in this vein — a whole book, even — and, wow, I would queue up for that. She is great. I wrote about this briefly on KinderComics, on October 9. Love & Rockets #4, 5, and 6, by Gilbert Hernandez and Jaime Hernandez (Fantagraphics). I love no comic book series more than this one. Launched in 1981, L&R has lasted long enough to come to terms with its own history, and recent stories by Gilbert and Jaime have done that, with lived-in characterizations, loving revisitations, reflections on growth and change, and, most importantly, fresh, disconcerting, surprises. Just when I think I’ve got them pegged — just when I’m getting all nostalgic about their work — they throw another curve ball, and I get a little shock, a mild sense of disorientation. And I love it. Funny, poignant, masterfully drawn comics, always a pleasure. This year’s issues have been particularly great, confirming yet again that Los Bros are two of the best cartoonists alive. Sex Criminals, by Matt Fraction and Chip Zdarsky (Image Comics). This risk-taking genre mashup, a ribald, at-times explicit tale of desire, shame, romance, and crime, no longer quite works as a traditional comic book serial: long wait times have attenuated its suspense, and these days each new issue requires me to reread the previous ones just to stay more or less unconfused. (I’ve had that same experience with L&R.) Sex Criminals is an odd duck, pushing at the seams of several genres at once, and sometimes it falters. Further, its queasy comedy may sometimes seem glib. But I think it's terrific; from my POV, Fraction has far outgrown glibness. Further, I delight at Fraction and Zdarksy’s self-questioning way of complicating, perhaps even sabotaging, their initial premises. Gutsy, weird stuff. So, I look forward to reading this series to its end. And, on the more obviously commercial, work-for-hire side of serial comics, there's the final arc of Mister Miracle, by Tom King and Mitch Gerads (DC Comics). By rights I should hate this, but I don't. A dark, depressive update on Jack Kirby's beloved Fourth World character — the super escape artist, emblem of freedom and possibility — this story begins with the hero trying to kill himself, and goes downhill from there. But then uphill, maybe? The final movement, and last couple of issues, are enigmatic but guardedly affirming. Overall, though, this series is harsh, troubling. King, the direct market's laureate of depression and trauma, works in an Alan Moore-ish vein, with a similar clinical formalism that offsets the bruising emotional content. At times ultraviolent, at other times perversely comic, this is one revisionist superhero comic that actually seems to be trying to say something. I can't say I love it, but it has a mind, and some genuine ache, behind it. Increasingly, I find myself rejecting nostalgically literal takes on Kirby, and this came as a sort of tonic relief from that mode — something oddly personal. So, yeah. Finally, I also want to mention two picture books from 2018 that do not seem to be "comics" in the usual sense but happen to be by established comics artists and are wonderful visual poems: They Say Blue, by Jillian Tamaki (Abrams). A young girl looks at the world around her in light of what people conventionally “say” about it — and her thoughts deliver up the world anew, richer and more beautiful than convention will allow. The landscape, the weather, the water, the sky, and small observations about everything: They Say Blue builds out from these, in lyric rather than narrative form. The book steers into Romantic conceptions of the Child as naively wise and gifted with unblinkered sight — yet at the same time Tamaki thankfully includes notes of mundane business and everyday frustration, touches that ground the book’s sense of wonder. Very much an observational picture book in the modernist here-and-now tradition — Tamaki does not regard it as a comic — They Say Blue is visual poetry of a high order, and a drop-dead gorgeous book. Is there anything this supremely gifted artist cannot do? KinderComics reviewed this on April 26. We Are All Me, by Jordan Crane (First Second). Lately I've been teaching this picture book in English 392, and Crane recently came to my campus to talk with my class and other visiting students. This too is a lyrical picture book rather than a storybook, and in fact it is even less "narrative" than They Say Blue. Built around the concept of interdependence, We Are All Me is a brief but very rich poetic evocation of the web of life. It balances figural and abstract forms and creates its own system of colors and color-transitions, taking us from the individual human figure to the cycle of life and then into the atomic, even the quantum, level. As it moves toward the infinitesimal, it embraces the infinite. Finally, it brings us back to the human form, the individual "me," yet also the affirming collective "we." This is not a very original conceit -- indeed, the book builds upon a familiar, almost proverbial, wisdom -- but Crane realizes it with beautiful, glowing pages and a suite of braided and nested forms and inspired visual rhymes. The total effect is transporting. I have never seen a mass-market book with such fluorescent, eye-boggling color. Quite lovely: a book to get drunk on.  The above are the graphic books that have meant the most to me in 2018. They have stood out in mind and stayed with me, and in many cases moved me. I’ve read and re-read them, stared at and savored and wondered over them. In my opinion, it's been a great year for comics in the US, and there's lots more to love beyond these few titles. Man, do I have a lot of catching up to do as a reader! For example, there are new titles or new US translations by Emily Carroll, Junji Ito, Nagata Kabi, Hartley Lin, Héctor Oesterheld & Alberto Breccia, Katie O'Neill, Keiler Roberts, and others that I want to experience. Plus, there's a number of ongoing floppy-to-trade serials I am seriously behind on, such as Monstress, Saga, and Paper Girls, and there are promising new floppy series to track (The Seeds and Bitter Root, among others). In fact, there's a ton of promising new work out there! (And what about the comics I don't yet know anything about, the genuine surprises? Maybe this week's CALA festival will once again introduce me to a few. So much to learn!) And, no, I haven't yet finished Jason Lutes's collected Berlin. I'm saving it. :) PS. I have to say, First Second Books is my Publisher of the Year. They have put out such strong books in 2018 (including ones by Sarah Varon, Graham Annable, and Aaron Renier that very nearly made the above list). Theirs is one amazing catalog. Twelve years and counting, they've been bringing great comics into the world, but 2018 in particular has been a superb year for them.

3 Comments

Katharine Capshaw

12/7/2018 12:37:17 pm

Thank you, Charles. This list is insightful and rich.

Reply

Charles Hatfield

12/10/2018 08:22:51 am

Thank YOU, Kate. Glad that this list is useful to you!

Reply

Charles Hatfield

12/13/2018 12:34:41 pm

UPDATE: At CALA 2018, I was at last able to meet cartoonist Hartley Lin, and purchased his graphic novel Young Frances (collecting a serial from his splendid Pope Hats comic book). Rereading this story in one go, I’m, once again, floored by it. Young Frances is a work of designing subtlety, peppered with great, unnerving moments, and boasting a winning couple of characters in Frances and her friend and roommate Vickie. These people feel real to me while I’m reading about them. The book has plenty of darkness and desperation in it, but seems to arrive at a kind of ambiguous happiness, though one that promises no escape from the darkness. I love the unsettledness, but also the generosity, of the ending, which manages to be affirming and complicated at once. The voices of the people Lin has conjured, the worlds in which they live, the rhythms of the storytelling, the spareness and economy, and the just flat-out terrific writing, make Young Frances that rare thing, a graphic novel that coheres as one and leaves me thinking about the characters in it long after closing the covers.

Reply

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

Archives

June 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed