|

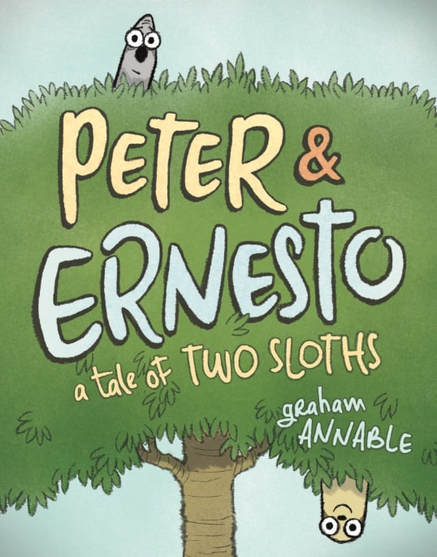

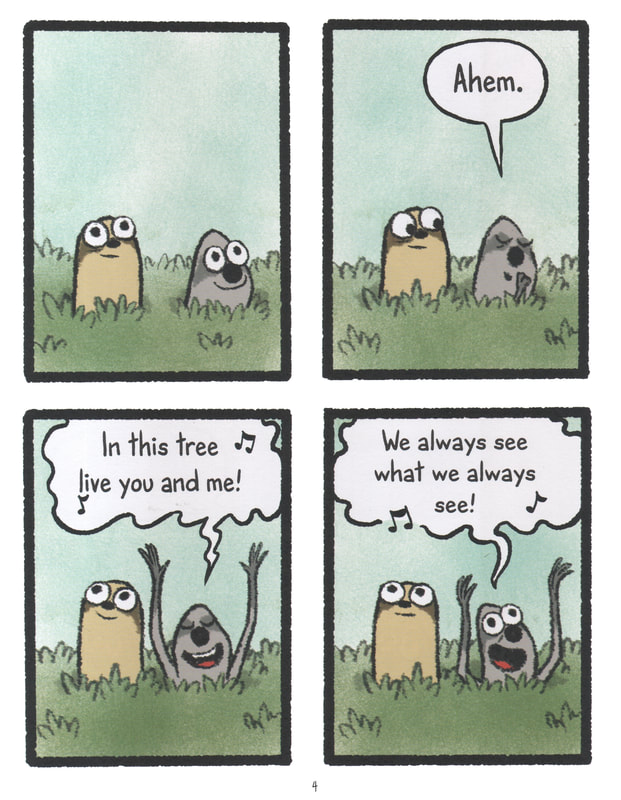

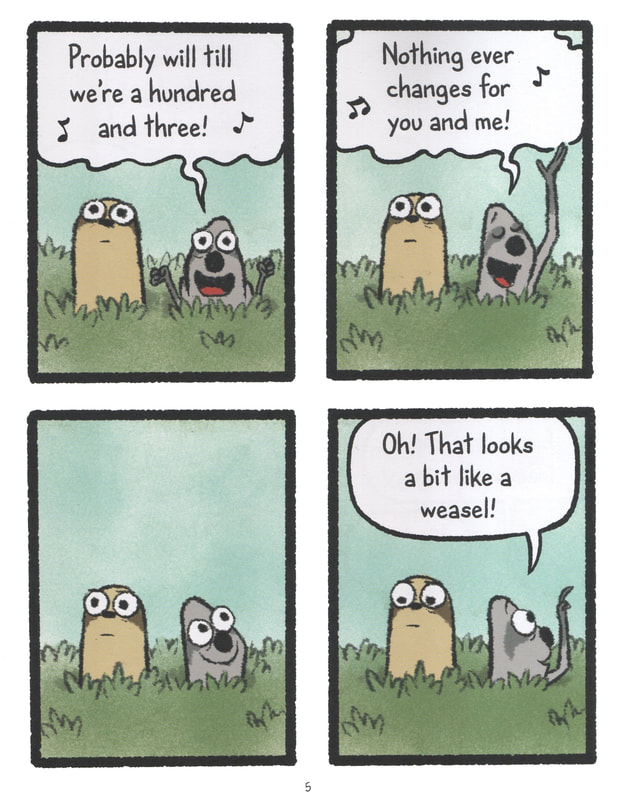

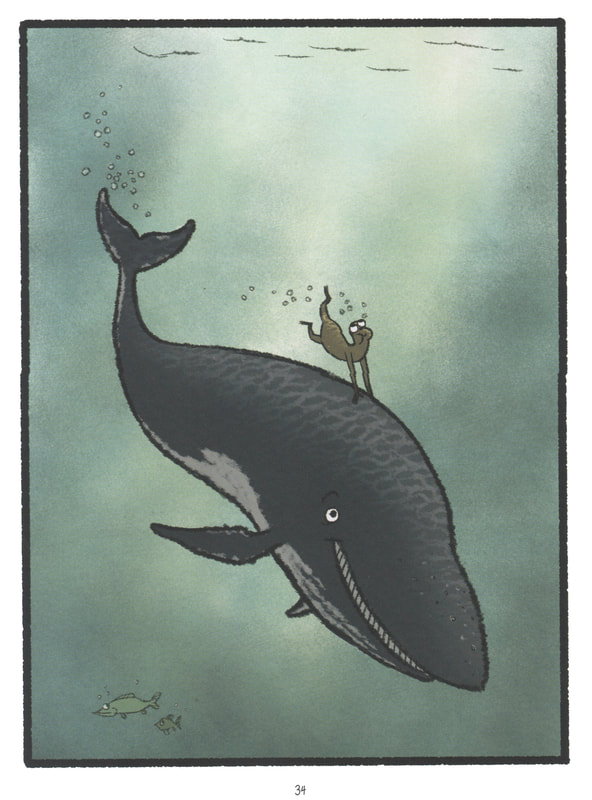

Peter & Ernesto: A Tale of Two Sloths. By Graham Annable. First Second, 2018. ISBN 978-1626725614. $17.99, 128 pages. Book design by Danielle Ceccolini. Cartoonist, animator, and director Graham Annable (The Book of Grickle, Puzzle Agent, The Grickle Channel on YouTube, etc.) is a wickedly smart humorist working his own distinctive vein of anxious, twitchy, sometimes disturbing comics, films, and games. At times his work is very dark: some readers may remember his tale "Burden" (Papercutter #3, Fall 2006), reprinted in The Best American Comics 2008 (edited by Lynda Barry). Sometimes his work is more eager to please, but still uneasy; I'd place the Laika film The Boxtrolls, which he co-directed, in that category. The various Grickle projects are pure Annable, a window onto his sensibility: nervous humor, odd beats, and bug-eyed characters who look a lot like Annable's own thumbnail image from Twitter: Peter & Ernesto is Annable's first children's book. It's terrific and strange: a buddy story in which the two buddies are mostly separated. One, Ernesto, seeks adventure and new experience. The other, Peter, craves security and sameness. They happen to be sloths. Their story begins in a treetop, as together the two of them indulge in the happy pastime of reading the shapes of clouds: a friendly idyll. Right away, though, the two diverge. As Peter joyfully basks in the unchanging familiarity of their lives, Ernesto begins to look—well, restless. And almost worried. As if the smallness of their shared world is closing in on him. The scene is tender, anxious, and funny, like the book as a whole: From there, Ernesto takes off to see the world, going where Peter dare not follow. But Peter’s concern for Ernesto overtakes his fear, and he sets out after his friend as if to protect him from the wide world—even though Peter can hardly bear to face that world himself. For much of the book, then, Peter follows belatedly behind Ernesto, so that the reader re-experiences places they have already visited, pages earlier—but it’s much different the second time around. As Ernesto revels in the unexpected thrills of his frankly improvised journey, Peter encounters the same scenes, and hurdles, with fear and trembling. There’s a lot of loopy business en route, much of it involving other comic animals, before a neat, affirming close. Annable’s comic timing his great, he mines Peter’s anxious qualms for tender, empathetic humor, and the world comes out seeming like a grand place. Implicitly, Peter & Ernesto is an odd-couple narrative for both brave, venturesome kids and diffident, anxious ones. There are a lot of children’s stories like this: depictions of sometimes contrasting and yet loyal friends. I hear an echo of Arnold Lobel’s Frog and Toad books here (Frog and Toad Are Friends and its four sequels, 1970-1979), and Annable has said that they were indeed an influence. Sesame Street's Ernie and Bert come to mind too. What I particularly like about Peter & Ernesto is its deft cartooning and comic timing—and the way Annable, a poet of nervousness, gets me to sympathize with both the world-conquering Ernesto and especially the timorous, uncertain Peter. Drawn in Photoshop with customized brushes, Peter & Ernesto boasts a ragged, trembling line and organic look. It is beautifully and subtly colored: Peter and Ernesto live in a great green and blue world. Yet it’s Annable’s shivery lines and coarse textures that set the book apart—those, and his animator’s knack for distinctive and expressive character design. Peter and Ernesto are very easy to tell apart. As for the other players—monkeys, dromedary, tapir, whale, and so on—they are great cartoon characters, all. Annable keeps things schematic and clear, with page layouts that vary discreetly among full-page panels and two, three, and four-panel grids (oh, but there's one glorious exception that you'll have to see for yourself). Every panel is a rectangle bounded by the same thick, ragged black line, but this sameness grounds the book and brings it to life, rhythmically. All parts work together. In short, Peter & Ernesto is a little triumph of spare, funny cartooning, and comes highly recommended. A sequel is coming. That's good news. First Second provided a review copy of this book.

0 Comments

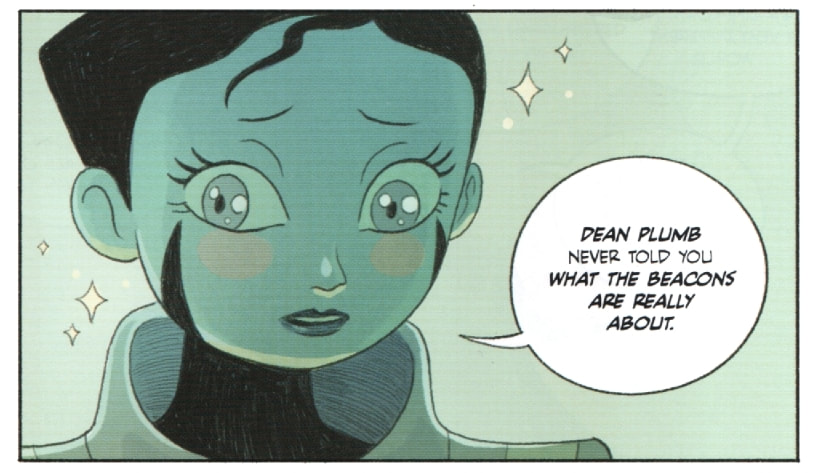

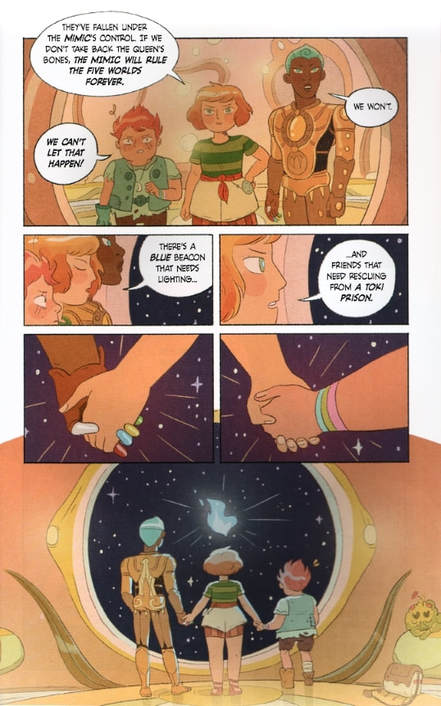

5 Worlds: The Cobalt Prince. By Mark Siegel, Alexis Siegel, Xanthe Bouma, Matt Rockefeller, and Boya Sun. Random House, May 2018. Paperback: ISBN 978-1101935910, $12.99. Hardcover: ISBN 978-1101935897, $20.99. 256 pages. Epic fantasy is a balancing act. On the one hand, its make-believe settings tend to be rule-governed and to strive after internal consistency, as if some kind of voluntary constraint were needed to hem in and discipline the pure exercise of fancy. We have to know that the characters, however magical, won't be able to do just anything they please, and that the worlds won't simply change in mid-story to suit the storyteller's whims (anyone who has ever played Dungeons & Dragons with a very whimsical DM knows how annoying that can be). Tolkien's Middle Earth has set a standard: that high fantasy worlds are to be approached with something like the self-discipline of historical fiction, even if that kind of discipline belies the very term fantasy. On the other hand, epic fantasy series, as they sprawl, often reveal new things about their worlds that shift the terms of our understanding. They elaborate, giving us more and more backstory that impinges on, or changes the stakes of, the story we're reading. Multi-volume fantasies, as they ravel out, tend to disclose (or discover) more about origins or antecedent conditions, uncovering deep foundations that may generate new problems. Even Tolkien, who crafted a history of Middle Earth before he publicly shared that world, famously said that The Lord of the Rings "grew in the telling," which I take it means that the book (ultimately trilogy) ended up drawing in more and more of the mythic backstory as he had privately envisioned it. Of course, there are also epic fantasy series written without the same strict dedication to consistency: say, Zelazny's Amber, with its odd, shifting rules. Such shifting or feinting may betray Tolkien's disciplined mode of high fantasy, but I confess I enjoy twisting, ramifying plots that reveal more of a world to me, even when the twists undermine what I thought I knew about the world at first. Consider the way Rowling's Harry Potter turns out to be a multigenerational saga set in a world more layered, and corrupt, than the first book shows, or the way Le Guin’s Earthsea, in its later books, dismantles its own patriarchal foundations, or the way Jeff Smith's Bone, in the seventh-inning stretch, gets more tangled and complex. In a satisfying fantasy epic, we will come to believe that all the complications were foreordained and fit perfectly. Besides self-consistency, then, I do enjoy the continual deepening of fantasy worlds. I bet a lot of readers do. As we travel the worlds, we learn, even as the heroes do, how complex the worlds truly are. That, I think, is the effect that 5 Worlds is going for. 5 Worlds, a collaborative graphic novel series that launched last year, does not quite persuade me that everything has been worked out, or that everything fits. Its cluster of worlds is complicated, even baroque, yet its plot is a breathless, rocket-propelled blur. I reviewed the first volume, The Sand Warrior, here recently, and complained that the tale suffered from tangled plotlines, a frantic pace, and too much downloading of mythic backstory. The second volume, The Cobalt Prince, is due out this week, and guess what? It has all those same qualities. The Cobalt Prince does not "solve" the "problems" of The Sand Warrior, and there are moments where its storytelling gets muddled. However, the book is splendidly imaginative, enough so to make its problems into virtues—which is to say that I'm glad to be revisiting 5 Worlds and exploring its universe. There's a lot going on here, plot-wise, and the book is a delirious exercise in graphic world-building. Thankfully, it remembers to round out and humanize its characters as it goes, and so attains a poignancy that the first volume lacked. If The Sand Warrior seemed promising, The Cobalt Prince is grand. By way of recap (here I'll crib from my first review), 5 Worlds is a science fantasy co-scripted and designed by cartoonist Mark Siegel and his brother Alexis Siegel and then further designed and drawn by three other cartoonists, Xanthe Bouma, Matt Rockefeller, and Boya Sun. Its plot revolves around an ecological catastrophe that threatens five rival yet interconnected planets. These are Mon Domani, the so-called Mother World, and her four satellites, each with a distinctly different culture. All five worlds are drying out and dying of heat death. Per an ancient prophecy, this disaster can be averted by relighting the long-dormant "Beacons” on each world, but not everyone believes the prophecy. Rivalry among the worlds gets in the way of cooperative problem-solving, and a shadowy adversary known as the Mimic (a sort of Dark Lord) exploits this rivalry in order to sow invasion and war. Our heroine Oona, an unfledged “sand dancer” of Mon Domani, seeks to relight the Beacons and stop the Mimic, with the help of a resourceful urchin named An Tzu and a sleek android called Jax. The first book centered on Mon Domani, but The Cobalt Prince moves on to other worlds: Toki, home of the despised, racially Othered "blue-skins," and Salassandra, home to diverse religious orders. Though Toki is the main theater of action, the plot caroms from place to place. When first I saw The Cobalt Prince, I noted Jax's absence from the cover—and sure enough Jax gets sidelined along the way, as if his story were one too many for this book. A plethora of new characters more than fills his space, and The Cobalt Prince becomes a roll call of unfamiliar names assigned to familiar archetypal roles: Master Elon, a mentor and outlaw; Ram Sam Sam, a cute ectoplasmic critter; O'Zirg, a shopkeeper; Anselka, a healer; and Magda, another mentor, this one a Master Yupa or Obi-Wan type who possesses essential knowledge. These figures become helpers or donors to our heroes (in folklorist Vladimir Propp's sense). They also bring new info, as, in good fantasy fashion, The Cobalt Prince dives into fresh elaborations and disclosures. So, even as this second book explains and solidifies things that happened in the first, it also changes the terms of the first, complicating what was already tricky. Along the way, it changes how we think of Oona (and how she thinks of herself) and makes Oona's sister Jessa, a morally ambiguous figure in the first book, into the linchpin of the plot. The sisterhood of Jessa and Oona turns out to be this book's core. Narratively, The Cobalt Prince, like The Sand Warrior before it, is a mixed bag. On the plus side, the book's elaborations are emotional as well as clever, giving it more gravity than its predecessor. Also, I like the way its plot presses on the issue of racism as both personal animus and systemic oppression. In this story, distrust and division are keyed to skin color and culture, and at times racist hatred or fear threatens to misdirect our heroes. The challenges of transcultural understanding lend the frenetic, pinballing story greater depth. However, some of that subtlety gets fumbled along the way to a grand finale: a gathering of forces that, in its rigging, reminds me of The Hobbit's Battle of Five Armies, though sadly it comes across less clearly. The book, finally, stacks up too many plot points at once. A frenzied fight between giant, godlike avatars is particularly confusing, as those beings are possessed first by one side, then by the other, blurring the action's meaning. I had to reread some pages two or three times to understand what was happening, to whom, and why. When I finally did "get" it, it was rather glorious, but on first reading I was a bit lost. An anticlimactic but necessary "epilogue" does the work of sorting things out and springboarding readers onward to the next volume. I know I'll be there, waiting to see what complications the plot delivers next. Like its predecessor, The Cobalt Prince is beautifully designed, drawn, and colored, a rapturous outpouring of images. The five-person 5 Worlds team continues to be a collaborative miracle. The book wears its visual influences on its sleeve: a temple scene on Salassandra recalls Moebius; a chase scene involving starships and an "escape pod" cannot help but evoke Star Wars. Miyazaki looms large: treks through a post-apocalyptic "wasteland" echo the opening of Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind, while the final battle invokes Princess Mononoke's giant Forest Spirit but also its sense of ecological renewal, as the dead wasteland blooms green again. 5 Worlds, then, is frankly an exercise in allusion and synthesis. The reason I not only tolerate but savor these familiar elements is that, against all odds, the 5 Worlds team makes everything seem of a piece visually. 5 Worlds continues to be a grand experiment that seems ever in danger of flying off the rails. I hope the books to come will slow down, find their feet narratively, and deliver their action more clearly. I look forward to seeing how the team's world-building and piling-up of ideas comes together as an epic whole. Will everything fit perfectly? Of course I can't say yet, but the journey is head-spinning. Random House provided a review copy of this book.

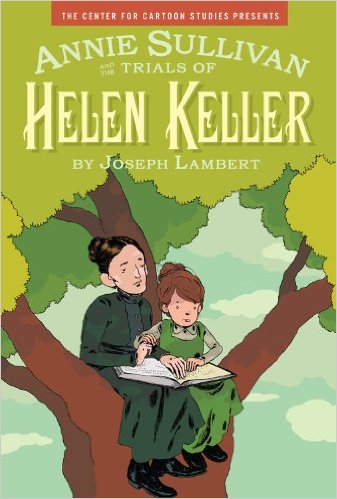

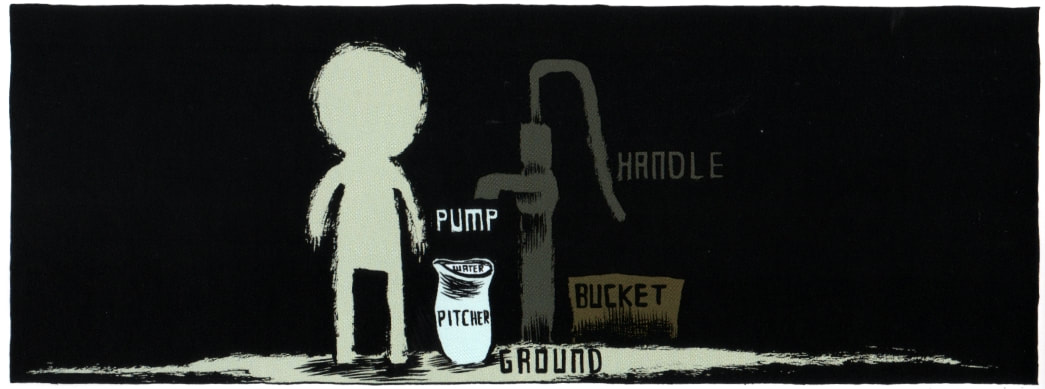

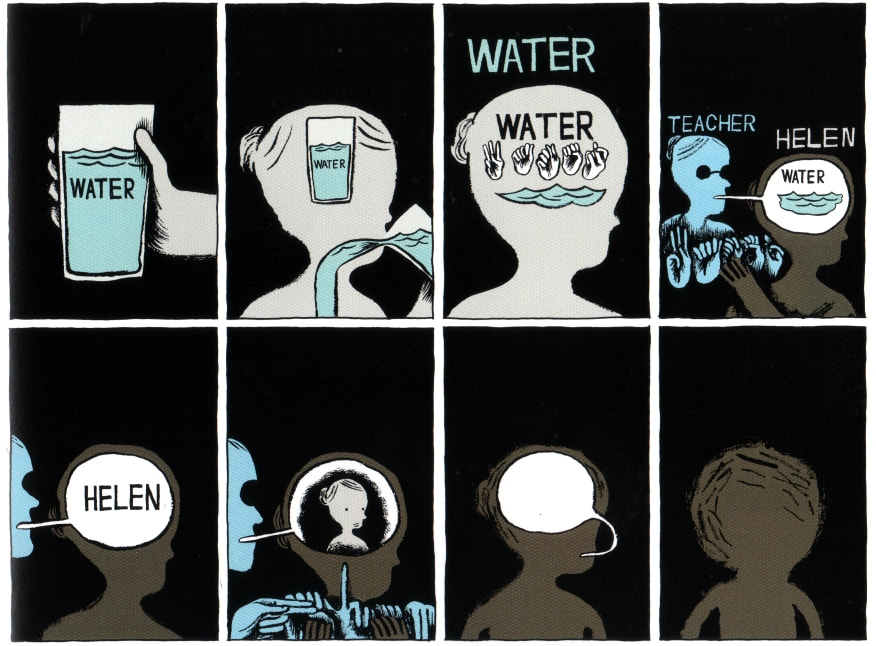

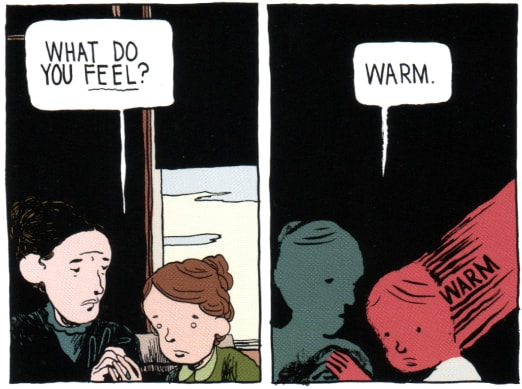

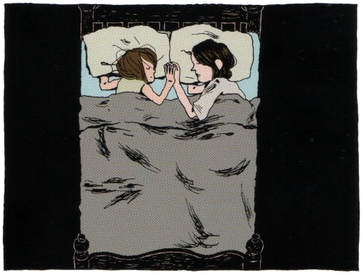

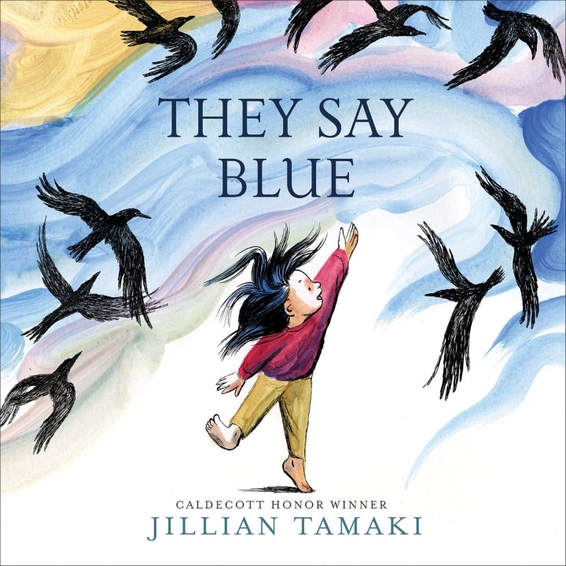

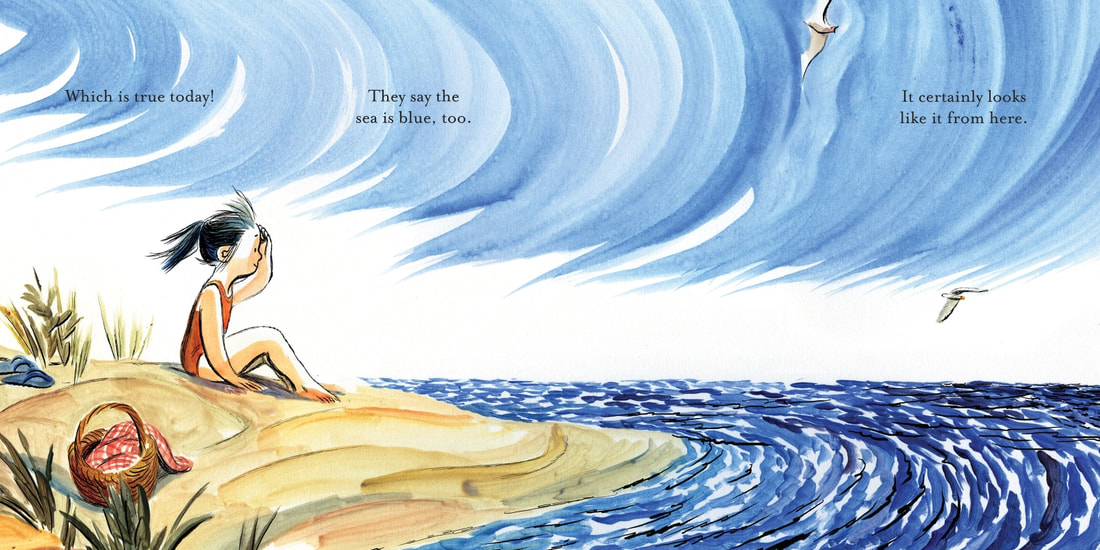

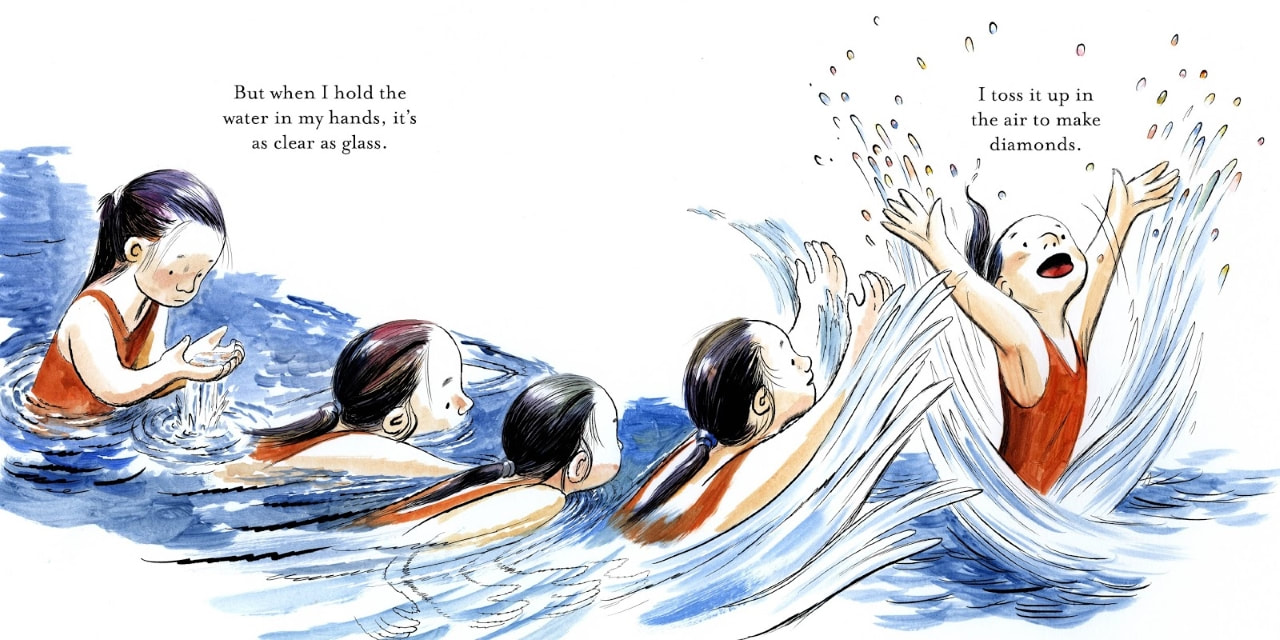

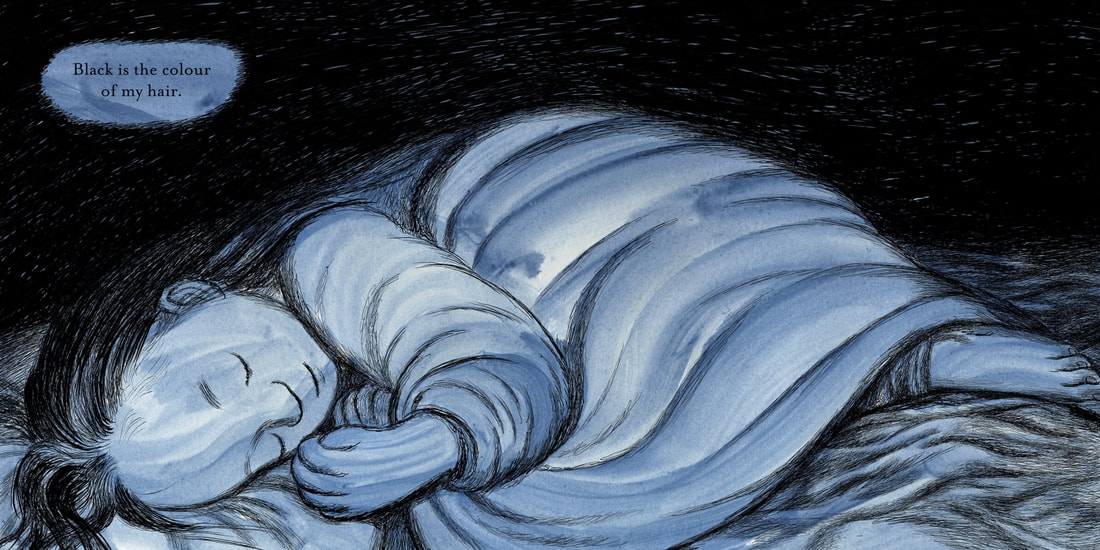

Annie Sullivan and the Trials of Helen Keller. By Joseph Lambert. Edited by Jason Lutes. Disney/ Hyperion, 2012. ISBN 978-1423113362. $17.99, 96 pages. Winner of the Will Eisner Award for Best Reality-Based Work, 2013. I have a dozen copies of Joseph Lambert's Annie Sullivan and the Trials of Helen Keller in my office. It's that good. I bought most of those copies through Alibris just over a year ago while preparing to teach my grad seminar "Disability in Comics." I had always intended Annie Sullivan to be a required book in that class, along with such other comics as Binky Brown Meets the Holy Virgin Mary, The Spiral Cage, Epileptic, El Deafo, and Hawkeye: Rio Bravo. In fact Annie, along with José Alaniz's Death, Disability, and the Superhero, was one of the books that inspired me to teach the class in the first place. When I discovered that Annie was out of print, I lost my mind a bit, but then decided to scrounge up multiple used copies on my own dime and turn my office into a lending library. So, I ended up with a lot of Annie, and loaned out copies for several weeks. It's criminal that this modern classic is out of print – and I hope someone does something to change that soon. Annie Sullivan is part of a series of comics biographies packaged by the Center for Cartoon Studies for publisher Disney/Hyperion (2007-2012). These include books on Harry Houdini, Satchel Paige, Amelia Earhart, and Henry David Thoreau. All the books are hardcovers that run about 100 pages, and all are good; John Porcellino's Thoreau at Walden is wonderful. But Lambert's book, I believe, is one for the ages. Why do I admire this book so much? Lambert, whose work I came to know through The Best American Comics 2008 (edited by Lynda Barry) and then his story collection I Will Bite You! (2011), is simply a great cartoonist. His work displays a patience for careful breakdowns and repetition which approaches that of Harvey Kurtzman or of a top-notch humor strip artist. His drawing is simplified in appearance but also nuanced and emotionally precise, capable of capturing crucial subtleties of gesture and expression. Further, he has an appetite for expressing feeling and sensation through variations in traditional form; he can make a regular, unvarying grid seem musical and powerful. Feeling and sensation are the life's blood of Annie Sullivan, a book that works cannily, in an austere, rhythmically controlled way, to convey how its title characters experience the world in spite of (or through the filter of) isolating sensory impairments. Lambert does this with a poet's command of meter and a true biographer's interpretive sensitivity. One of the things Annie Sullivan does so well is inevitably, perhaps cruelly, ironic: it finds ways to visually convey non-visual experience, particularly haptic experience: the experience of handling things, of placing your hand in someone else's, of spelling things out with your fingers, and so on. Annie Sullivan taught Helen Keller, who lost her sight and hearing before she turned two, to recognize things in the world with her hands, and to communicate through finger spelling. Keller wrote in her autobiography, The Story of My Life (1903), that her tutor Sullivan revealed to her "the mystery of language," a gift that, she said, "awakened my soul, gave it light, hope, joy, set it free!" Lambert does a stunningly smart job of communicating both how Sullivan taught Keller and how hard it was. His pages convey Helen's haptic world and her opening-out into written language, using a range of techniques: tight, inescapable grids; nearly all-black panels and stark contrasts of light and darkness; isolated and stylized figures; systematic color-coding of figures and objects; inventive rendering and placement of single words; and stylized iconic hands to represent finger spelling. Formally ingenious, these techniques are also moving, for they show the extent of Helen's isolation, the intense, mutually dependent relationship between Helen and Annie, and the cascading emotional consequences of Helen's growing literacy. In a profound sense, Lambert's book is about obstacles to communication, and how, in the singular Hellen/Annie relationship, these were overleapt. Again, to render haptic experience visually is unavoidably ironic. In my class we discussed not only the formalistic means but also the ethics of this approach, in comparison and contrast to other comics' visual depictions of non-visual experience (particularly Marvel's Daredevil). Annie Sullivan and the Trials of Helen Keller cannot perfectly convey Helen's phenomenal world. It cannot help but be an ocularcentric evocation of sightless experience. That's a problem. Yet the book is a highwater mark in the synesthetic use of comics' visual form to suggest life beyond the visual; in this, it strikes me as both ingenious and sensitive. Another thing that makes Annie Sullivan so strong is its dual focus on teacher and student. Sullivan comes off, not as some beneficent "miracle worker," but as a conflicted, heroically stubborn, frank, fierce, and deeply sorrowful person, shaped by her own visual impairment, her wretched years spent living in an almshouse, the tragic loss of her brother, and her just resentment of gender convention and the straitened roles available to women in 19th century America. Sullivan appears to have been a difficult and marvelous person, sometimes bitterly acerbic, and moved by abiding grief and anger. At times Lambert depicts her teaching of Helen as autocratic, harsh, even borderline abusive. Yet he also shows how and why it worked. Lambert, that is, portrays Annie with great empathy but also unsentimental candor. The book is tough-minded, sketching in the horrors of Annie's early life discreetly but powerfully and showing her resistance to the men and women who sought to control her. What's more, in its depiction of teacher and student together, Annie Sullivan avoids the triumphal cliches of children's biography. While Lambert rightly depicts Sullivan's breakthrough with her pupil as remarkable (the famous scene at the water pump, recounted in Keller's biography and in the many versions of The Miracle Worker), that is not the end of the story, and the book's second half delves into other "trials." Chief among these is an accusation of plagiarism that hurt Keller deeply, bedeviled her early efforts as a writer, and estranged Keller and Sullivan from their benefactors in the field of education for the visually impaired. In the end, what emerges is not a simple story of Helen's triumph over adversity but a complex sense of Helen and Annie's profound dependence on one another. In fact, the conclusion of the book is oddly melancholy, offering none of the facile reassurances that ableist stories of overcoming disability tend to offer. In sum, Annie Sullivan is a brilliant feat of writing as well as cartooning and design. It really is a shame that Annie Sullivan and the Trials of Helen Keller is out of print. I can't say that enough.  UPDATE: It's back in print! As of October 2018. Yes! They Say Blue. By Jillian Tamaki. Abrams Books for Young Readers, March 2018. ISBN 978-1419728518. $17.99, 40 pages. Jillian Tamaki (Skim, This One Summer, SuperMutant Magic Academy, Boundless, much more) has just done her first children's picture book, They Say Blue. It's a dream: a lyrical, drifting book about seeing and not seeing, about a world of colors, about raw perception but also how we reflect upon and try to make sense of our perceptions. Painted in flowing acrylics on watercolor paper, with overlays of inked drawing via Photoshop, They Say Blue consists almost entirely of full-bleed double-spreads dotted with short, vigorous bursts of text. Lavishly illustrated yet sparsely written (roughly twoscore sentences run through its twoscore pages), it is less a storybook than a visual poem, liquid, freely expressive, and unpredictable. It focuses on the aesthetic sense and restless intelligence of a young girl with an artist's eye, for whom ordinary things can be extraordinary. The young narrator treats common sights and happenings as festivals of color, light (or darkness), and warmth, even as she sees the world around her in a here-and-now, everyday sort of way. She comes across not as some idealized Wordsworthian poet-child (though the book does partake of that spirit, a bit) but as a believably curious and engaged girl. Wonder and watch are key words, and wonder well describes my own response to the book. In other words, They Say Blue is a credible and lovely evocation of a child's creative eye and voice. It recalls, for me, the pithy matter-of-factness of Krauss and Sendak's A Hole Is to Dig, or the free-associative riffing of Crockett Johnson's Harold. It's more visually extravagant than either of those, though, recalling how the modernist here-and-now picture books of the early 20th century, the kind championed by Lucy Sprague Mitchell and Margaret Wise Brown, captured children's daily lives and intimate concerns with simplified, streamlined prose-poetry yet also, often, with rapturous, brilliant images. Tamaki is working that same ground, in (as she has said) a quite traditional way. It's a tradition less about story than about a child's looking and thinking, that is, about being in the world. I think of Brown's books with Leonard Weisgard (such as The Noisy Book, The Little Island, and The Important Book) or of course her work with Clement Hurd (most famously Goodnight Moon) -- books about ordinary sensations or the reassuring rhythms of life. They Say Blue, you can tell by its very title, is about the young girl stacking up what "they" say against what her own experience tells her. It begins with a nonfigurative spread of pure blue -- a field of overlapping brushstrokes -- and the simple observation, They say blue is the color of the sky. But, as we turn the page, then the narrator measures what "they say" against her own vision, in this glorious spread: Turning again to the next spread, we see the girl swimming through, gazing at, and splashing in seawater: five drawings of her combined into a single image. In picture book critics' parlance, this is a clear case of simultaneous succession or continuous narrative -- but to me the important thing is that it shows the girl's immersion in experience, and her way of questioning what she is told, but then also reveling in what the world gives: But just as important as these rhapsodic passages are subtle ones that chip away at the idealization of childhood. My favorite is a series of two openings that together raise up but then undercut an idyllic fantasy. The first shows our narrator sailing in an imaginary boat over a field of grass "like a golden ocean" (more simultaneous succession: delightful movement). The next, though, shows a fairly bleak, rain-sogged landscape and the girl trudging homeward through foul weather, dragging her backpack behind her against a sky of grim clouds and dull grass. She concedes, It's just plain old yellow grass anyway. I can almost hear the weariness in her voice. Thankfully, it doesn't last, but I love the way Tamaki works these bum notes into the book. Make no mistake: They Say Blue is gentle. It is affirming. But I like the way it registers moments of doubt, bewilderment, and everyday muddling. Its poetry is an everyday sort of poetry, as in, Black is the color of my hair. / My mother parts it every morning, like opening a window. Opening a window on new ways of seeing familiar things is exactly what the book does. Many comics artists struggle when moving into picture books, but They Say Blue engages picture book form and tradition knowingly. Tamaki's recent interview with Roger Sutton at The Horn Book shows how well she knows the form, and artistically she takes to the picture book as if it were an answer to a question she has been asking. In a conversation with Eleanor Davis at The Comics Journal last summer, Tamaki admitted that "I can feel increasingly confined by the image part of comics," and reflected that, at least "for more commercial works, the images [in comics] need to be a lot more literal." She described herself as trying to "stretch that word-image relationship." More recently, in an interview with Matia Burnett at Publishers Weekly, Tamaki contrasted the experience of making comics with the experience of making picture books: They’re pretty different. The poetry and distillation of kids’ books, in word and image, is a completely different challenge. A lot of comics [work] is just grinding out pages, if the images communicate what’s happening, that’s usually good enough in a pinch. A picture book’s images have to evoke, which is much more ephemeral. My sense is that They Say Blue exercises a different part of Tamaki's artistry, while still being very clearly a Jillian Tamaki book. I'm glad. The book is beautiful, a work of deft visual poetry. It confirms that, as Eleanor Davis put it, "there is no one who is better."

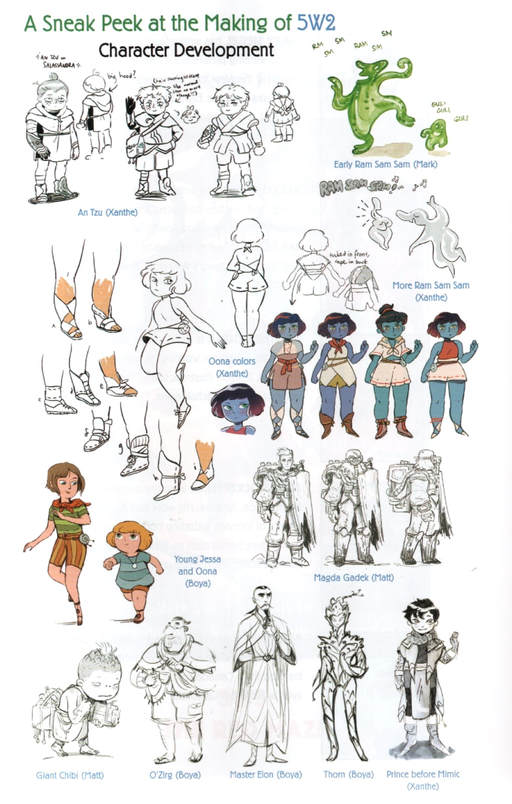

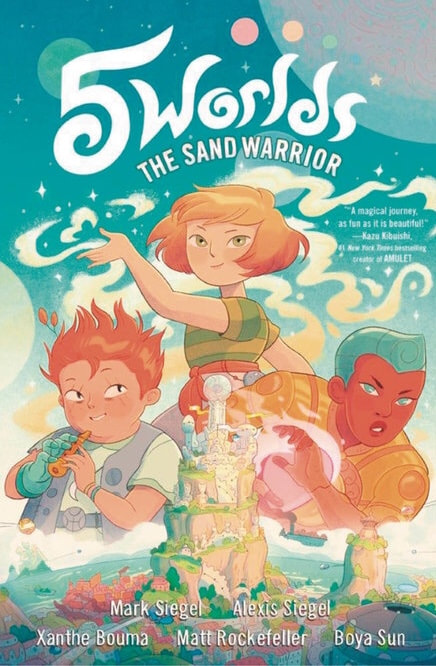

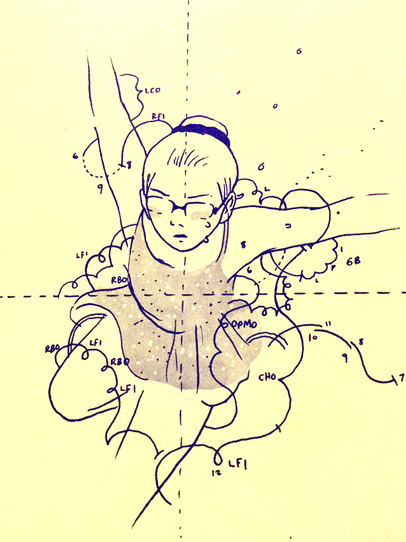

5 Worlds: The Sand Warrior. By Mark Siegel, Alexis Siegel, Xanthe Bouma, Matt Rockefeller, and Boya Sun. Random House, 2017. ISBN 978-1101935880. 256 pages, $16.99. A Junior Library Guild Selection. The Sand Warrior, a busy, fast-paced science fantasy adventure set in a wholly invented universe, teems with lovely ideas and designs. It is the first of a promised five-book series in the 5 Worlds (one book per world), and sets up a patchwork of different cultures, ecologies, technologies, and species. Indeed the book does some terrific world-building, the result of a complex collaborative process involving co-scriptwriters Mark Siegel and Alexis Siegel (brothers) and designer-illustrators Xanthe Bouma, Matt Rockefeller, and Boya Sun, working from an initial premise and designs by Mark Siegel. (Interestingly, Mark Siegel is founder and editorial director of First Second Books, but this is not a First Second title.) Reportedly, Mark Siegel conceived 5 Worlds as a project he would draw on his own (fans of Sailor Twain, To Dance, and his other books know that he could pull it off). However, as he and brother Alexis brainstormed the story, its plot and worlds grew so grand that he decided to turn it into a collaborative venture. Recruiting three recent graduates of the Maryland Institute College of Art — Bouma, Rockefeller, and Sun, who all met in a Character Design class at MICA — Siegel set in motion a complex, geographically dispersed teamwork, reportedly enabled by Google Drive, Skype or Zoom calls, texting, and secret Pinterest boards (see below for video links that shed light on this teamwork). The resulting book is remarkably consistent and aesthetically whole for such an elaborate process. It appears that Bouma, Rockefeller, and Sun became much more than hired illustrators on the project. They helped design and flesh out the worlds, and divided the page layouts and drawing (based on Mark Siegel’s thumbnails) in a selfless and seamless way. At the CALA festival last December, I bought a making-of zine (5W1 behind-the-scenes) from Bouma and Rockefeller, full of sketches and studies — a bit of archaeology for process geeks like me — and it intrigues me almost as much as the finished book. Visually, what has come out of that collaborative process is lovely. Story-wise, though, The Sand Warrior suffers from the greater ambitions of 5 Worlds. Its hectic, ricocheting plot zips forward too quickly for me to get a grip, even as it lurches into backstory with sudden, unexpected moments of info-dumping. Insertions here and there try to help the reader make sense of the 5 Worlds mythos (and do pay attention to the maps and legends on the endpapers). World-design and baiting-the-hook for future volumes get in the way of character development, even though the lead characters are soulful and troubled in promising ways. To be fair, there are moments of gravitas and emotional force amid the headlong action sequences, and there are consequential, irrevocable outcomes too. These impressed me. Yet I’d have liked to see longer spells of quietness, reflection, and clarity between the frenzied set pieces. The book actually does quietness rather well, but not enough; it has too much ground to cover. As a result, the plot comes off like a raw schematic of familiar things: prophecy, Chosen One, destiny, self-discovery, and reveals and reversals that I saw coming a long way off. When archetypal fantasy is stripped to its bones, too often the bones appear borrowed, and shopworn. It takes new textures to freshen those familiar elements. When the plot is streamlined to the point of frictionlessness (as in, for example, the breathless film adaptations of The Golden Compass and A Wrinkle in Time), we can all see that the game is rigged. My advice would be to slow down! Briefly, the plot of The Sand Warrior concerns the rival societies of five worlds: one great planet and her four satellites, each hosting a distinctly different culture. All five worlds are in crisis, dying of heat death and dehydration (a timely ecological allegory, ouch). According to an ancient prophecy, this catastrophe can be averted only by relighting the “Beacons” on each world, long since extinguished but still sources of wonder and controversy. Not everyone believes in this prophecy, and one world has plans of its own—prompted by the machinations of a dark, obscure adversary known only as the Mimic. Invasion and violence ensue. Our heroes, led by Oona, a mystically gifted yet diffident and halting “sand dancer,” seek to reignite the Beacon of their world and then defeat the Mimic. It’s all very complicated, with environmental and political workings and some of the plot machinery you'd expect to find in a fantasy epic with a prophesied hero. Bravely, The Sand Warrior tries to fill in all that detail on the fly; it foregoes the usual expository business of front-loading its mythos with a prologue, instead picking up backstory on the go. I appreciate that. However, this strategy poses challenges in terms of pacing and structure. Reading the book, I often felt as if I was being introduced to places and cultures just as they were being wrecked. The effect is like starting Harry Potter with the Battle of Hogwarts: too much too quickly, and with one or two familiar moves too many. By novel's end, even more interwoven secrets, and even more evidence of Oona's special nature, are hinted at—a touch too much—and the last pages almost desperately try to springboard into the coming second volume (out May 8). We close with obvious gestures toward self-realization and resolution but also toward open-endedness and further complication. Whew. Frankly, there’s too much to take in, and The Sand Warrior struggles to find a pace that is exciting but not skittish. Still, I look forward to further chapters in 5 Worlds. This five-headed collaborative beast, as frantic as its first outing may be, somehow has a single heart and speaks with a single voice. Sure, The Sand Warrior is overstuffed with known elements; the back matter acknowledges, among others, LeGuin, Bujold, and Moebius as inspirations, and many readers will also detect traces of Avatar: The Last Airbender and of Miyazaki (perhaps the beating heart of graphic fantasy nowadays). The story travels well-trod paths. But I like those paths; I like high fantasy. I also like the cultural complexity and diversity suggested by the book’s elaborate world-building. Further, the art attains a gorgeous fluency, with stunning color (reportedly Bouma did the key colors) and a lightness of touch, or delicacy of line, that recalls children’s bandes dessinées at their most ravishing. What’s more, the environments are transporting feats of design: giddy exercises in make-believe architecture and technology with a charming toy- or game-like density of detail. Naturally I want to stick around. I expect that The Sand Warrior will improve with rereading once more of 5 Worlds is revealed, and I look forward to seeing the characters through their troubles and gazing at whatever fresh landscapes they traverse along the way. In scope, and certainly in complexity of mythos, 5 Worlds compares well with Jeff Smith’s Bone — what it needs is patience, and pacing. Sources on the 5 Worlds Collaboration:

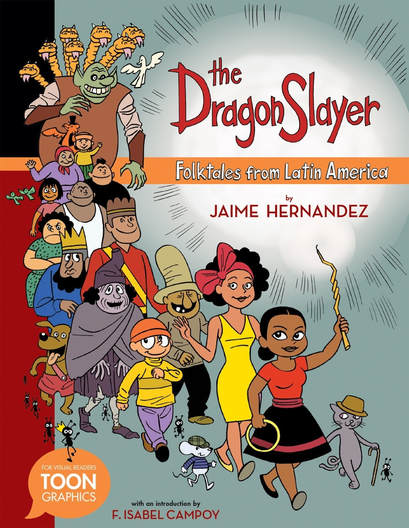

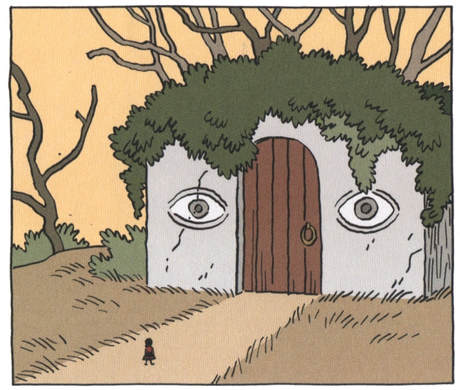

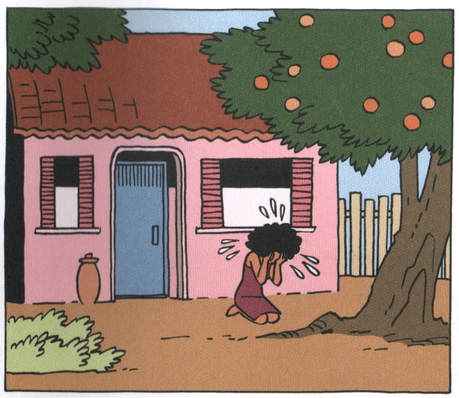

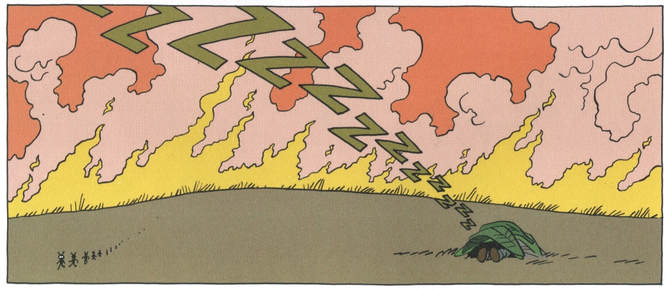

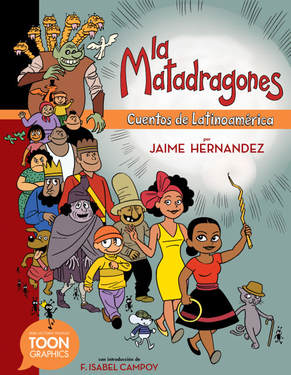

The Dragon Slayer. By Jaime Hernandez. TOON, 2018. Hardcover: ISBN 978-1943145287, $16.95. Softcover: ISBN 978-1943145294, $9.99. 40 pages. A Junior Library Guild Selection.Jaime Hernandez, one of the world's great cartoonists, is as lively and influential a comic book artist as you could hope to find. He has changed many readers' and artists' lives. His work on the Love and Rockets series (1981-now), in tandem with his brothers Mario and especially Gilbert Hernandez, proved that there was life and juice and relevance in the serial comics magazine, beyond even what many fans of the medium had dared hope. The punk, Latinx, and queer-positive aesthetic of L&R, along with its serious, in-depth storytelling and formal risk-taking, made for a revolution in comics, and Jaime Hernandez has deservedly been called one of the masters of the medium. The Dragon Slayer is not his first comic for children, as he's done a few short pieces for children's anthologies. Nor is it his first comic based on folklore: seek out for example "La Blanca," his version of a ghost story he heard from his mother, which he did for Gilbert's all-ages anthology Measles No. 2 back in 1999 (Gilbert too has made folk and family lore into comics: dig his "La Llorona," from New Love No. 5, back in 1997). Moreover, children and childhood memories are essential to Jaime's work in Love and Rockets. But The Dragon Slayer is Jaime's first real children's book. I have kid [characters] in my adult comics, but they play by my rules. Now that I’m writing for children, I’m playing by their rules. I was a little nervous because now I’m speaking directly to kids and to the parents who will let them read [the book]. So Dragon Slayer is something new for him. In fact it's a quiet collaboration: the book's back matter tells us that Hernandez read through many folktales to find the three that he wanted to adapt, and in this he was commissioned and helped by TOON's editorial director and the book's designer, Françoise Mouly. Mouly's team also deserves mention: in this case, designer Genevieve Bormes, who supplied Aztec and Maya design motifs that enliven the book's endpapers and peritexts, and editor, research assistant, and colorist Ala Lee. Like most books in the TOON Graphics line, Dragon Slayer includes some discreet educational apparatus, in the form of notes and bibliography -- more teamwork. Further, the book comes introduced by prolific scholar and children's author F. Isabel Campoy, whose collaborative book with children's author and teacher educator Alma Flor Ada, Tales Our Abuelitas Told: A Hispanic Folktale Collection (2006), is credited as one of Hernandez's sources. Campoy and Ada are key contributors here. (Another key source, albeit not as clearly announced, is John Bierhorst's 2002 collection Latin American Folktales.) All this is by way of packaging three 10-page comics by Hernandez, which are a delight, and are over too soon. I could read book after book like this from Hernandez -- the premise fits him beautifully. Hernandez has said that he liked the "wackiness" of these stories, and they do have that absurd-but-perfect, unquestionable quality of many folk tales: a sense of symbolic rightness and fated, almost-inevitable form in spite of the seeming craziness of their plots. Things happen that are preposterous and unexplained but just seem to fit, to click, because of the tales' use of repetition, parallels, rhythmic phrasing, and ritual challenges: stock ingredients, in anything but stock form. These folkloric patterns make the tales complete and rounded no matter how nonsensical they might appear at first. In crisp pages that rarely depart from a standard six-panel grid, Hernandez delivers the stories straight up, without any rationalizing or ironic distance, in clean, classic cartooning that communicates without breaking a sweat. Jaime is a master of seemingly guileless and transparent, but in fact subtle and artful, narrative drawing, and The Dragon Slayer does not disappoint. This has been billed as a "graphic novel," but it's no more a novel than other splendid TOON books like Birdsong, Flop to the Top, The Shark King, or Lost in NYC. What it is is a charming comic book that whets the appetite for more. Hernandez's cartooning benefits from the book's folkloric and scholarly teamwork, but the main thing is that the comics are marvelous. The title story, a feminist fairy tale with a light touch, focuses on an unfairly disowned youngest daughter who slays monsters and solves problems: a real pip. "Martina Martínez and Pérez the Mouse" (adapted from Ada's text) is an absurd story of marriage between a woman and a mouse, until it becomes a wise fable about panic and grief. "Tup and the Ants" is a lazy-son story in which the (again) youngest child proves his mettle with the help of a hill's worth of hard-working ants. All three comics surprised me and made me laugh out loud. I could call the book an anthology of lovely moments. It suffers no shortage of arresting moments -- panels that leap out: But what really makes these panels lovely is that there is no grandstanding in the art, only a terrific economy in visual storytelling: a streamlined delivery that carries us far, fast. Context is everything, and the book is not so much excerptable as endlessly readable. In short, The Dragon Slayer is a great book for Jaime Hernandez and for TOON, and one of the best folktale and fairy tale-based comics I've seen. I confess myself puzzled by its labeling as a TOON Graphic, which in the TOON system implies an older, more experienced comics reader, as opposed to TOON's Level 1, 2, and 3 books for beginning or emerging readers (I don't see this as a more complex comics-reading experience than, say, some of the Level 3 titles). But I do appreciate the oversized (7¾ x 10 inch) TOON Graphics format, which gives Hernandez a larger space to work in, more like that of a comics magazine. That suits his drawing and pacing. In any case, The Dragon Slayer is a sweet, short burst of smart, loving comics, and comes highly recommended. PS. A Spanish-language edition, La Matadragones: Cuentos de Latinoamérica, is also available in both hardcover (ISBN 978-1943145300) and softcover (ISBN 978-1943145317), priced as above. TOON provided a review copy of this book, in its English-language version.

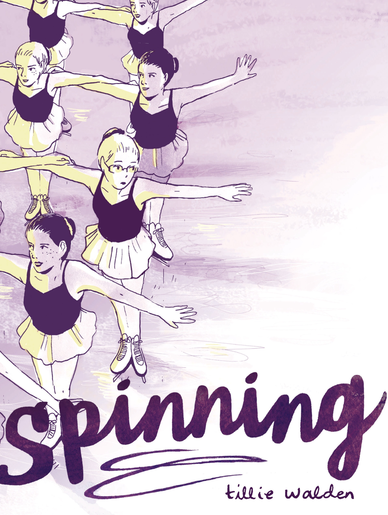

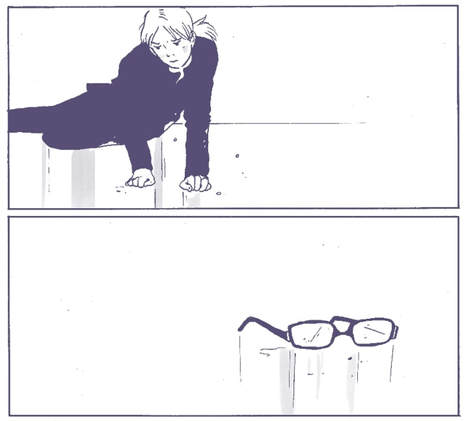

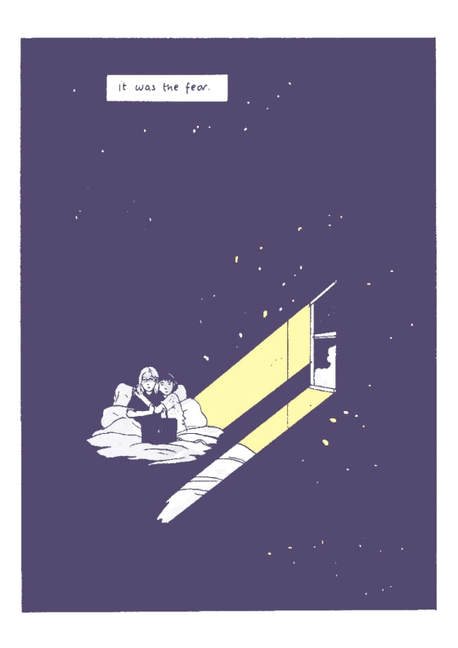

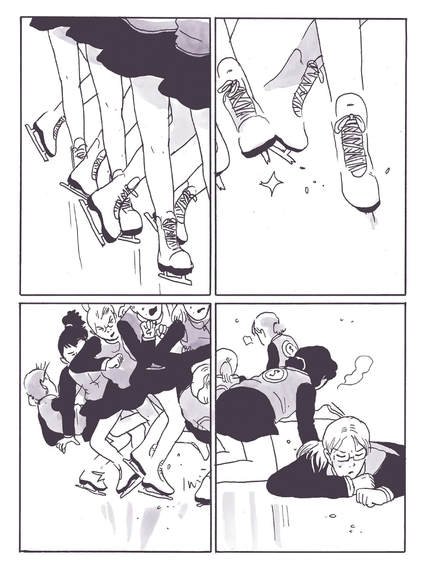

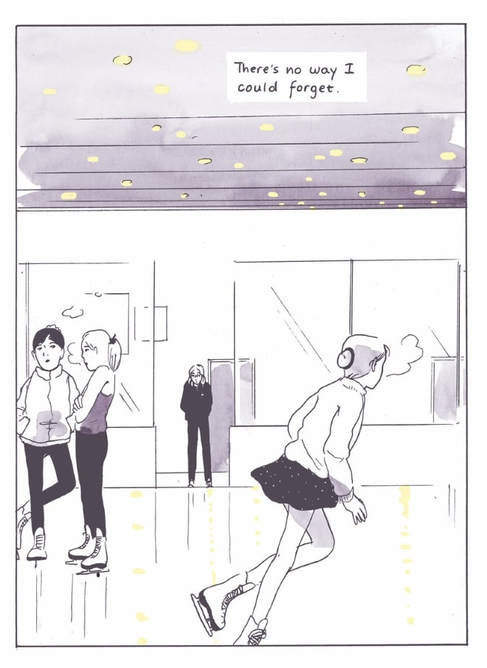

Spinning. By Tillie Walden. First Second, 2017. ISBN 978-1626729407. $17.99, 400 pages. Nominated for a 2018 Excellence in Graphic Literature Award. The feeling of waiting curbside for a ride in the predawn cold, watching headlights sweep through the darkness. Of peering out windows on sleepy car rides. Of early-morning arrival at the ice rink. Of locker rooms, benches, and earbuds, of lacing up your ice skates, everyone in their own little orbit, quietly, tensely readying themselves. Of being the new girl, of being sized up to see if you are “a threat.” Of skating across the ice, jumping and falling, your eyeglasses flinging off and away. The feeling of a teacher’s hands on your shoulders, helping you on with your jacket, and the inward recognition that you are gay. Of sidelong glances in a classroom, “dizzy” with longing. Of walking in a crowd of girls, talking about Twilight (Edward or Jacob?), while hiding who you are. Of playing “never have I ever” with the girls while hiding who you are. Of passing. Of trying to recreate, as a skater, with your body, the “tiny graphs and charts,” the “intricate patterns and minute details,” of an instruction book. Of desperately holding hands during a synchro skating routine. Even as the speed is “ripping them apart.” Holding on for dear life. Of friendship as a lifeline. As rivalry and sympathy intermingled. The feeling of being judged, as your teammate speeds up to walk a few paces ahead of you. Of winning and losing, of exulting in first place and weeping when you lose. Of knowing that you cannot always be the one that wins. The tears of your competitors, and your own. The dread of the school bully, rendered faceless in memory but still so powerfully there. Your hands nervously playing in your lap, or gripping your knees. Your teacher questioning you. The feeling of falling asleep next to your brother by the light of a laptop screen. Of crying from the makeup in your eyes. Of pulling a blanket up over your head. The sight of the girl you like stretching, and quietly smiling at you. The feeling of being alone with her. Of love, bounded by fear. Of kissing: I didn’t know it would feel like that. Of capering in a hotel room, alone, free from anyone’s judgment. Gazing into your reflection in the surface of a vending machine. The felt “eternity” of a three-minute skating routine. Feet in the air, in mid-jump. Stares and glances. Stares and glances. Girlhood as competitive arena. The feeling of being tested, and failing. Of being alone in a closed room with a tutor who treats you as a thing. The memory of his hand. The feeling of coming out, in a broad, silent room crossed by a slanting beam of sunlight, your mother huddled, tense. Of coming out to your music teacher, in a loving embrace. The sensation of drawing. Of time collapsed into drawing. Of a skate remembered as a nervous, tight grid of panels. Of moves and thoughts flickering. Of falling. Oh my god / my coach is looking at me / the audience shit / the judges The sight of oncoming headlights like round staring eyes. The memory of his hand. Of quitting skating. Walking away.

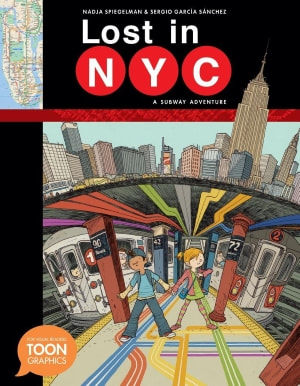

Driving away, crying. Of returning to the rink, once more, just to prove that you can leave. (There’s no way I could forget.) For all these experiences, and many more--so finely observed, so precisely caught, in a style at once tense and graceful, minimal yet conveying every telling detail, rigorous and yet so light and free—for all this, Tillie Walden’s memoir Spinning is an unforgettable comic, the kind that gets inside your mind and heart. I cannot recommend it highly enough. Lost in NYC: A Subway Adventure. Written by Nadja Spiegelman, illustrated by Sergio García Sánchez, and colored by Lola Moral. TOON Books, 2015. ISBN 978-1935179818. $16.95, 52 pages. A Junior Library Guild Selection. From time to time, Faves will offer brief capsule reviews of what I think of as key titles in my library: Lost in NYC is my favorite of the TOON Graphics to date (among the new books, that is—the translations of Fred's Philemon are also a delight). A short comic in picture book format, but as dense with detail as a graphic novel, Lost in NYC works in busy, hide-and-seek, Where’s Waldo? mode. It rewards attention, in fact perfectly demonstrates the idea that comics are a rereading medium. A valentine to New York and its subway system (the book is licensed by NYC's Metropolitan Transportation Authority), Lost in NYC depicts a school field trip to the Empire State Building, and gives a wealth of info about how to navigate the Big Apple (including a detailed subway map). Along the way, it tells the story of an awkward “new kid” in school who has just moved, feels out of place, and doesn’t trust anyone—until he and his field trip partner get lost and have to figure out how to rejoin their school group. The story depicts the new kid’s loneliness and bluff attempts to deny it with a rough honesty, but (unsurprisingly) reaches an uplifting conclusion: the field trip becomes a rite of passage, in a manner familiar from many picture books about first experiences. The pages, though, are the thing; they dazzle in their intricacy and attention to geography and culture. Sánchez’s cartooning is lively yet sly. The packed spreads, so much fun to wind through, turn up small surprises with each reading. Often the spreads use continuous visual narrative (i.e. repeated images of characters moving across a single page or opening) to show the kids negotiating the crowded city. Along the way, Lost in NYC has a lot to say about city life, mobility, access, and diversity (the art implies myriad mingled cultures). Thus the book invites comparison to other recent children's titles that envision cities as vast and pluralistic communities (for example, Matt de la Peña and Christian Robinson’s much-admired 2015 picture book, Last Stop on Market Street). It also tackles the challenges of moving and building new friendships. The plot is simple, and the outcome never in doubt, but the book puts the teeming cityscape to great use, not just as a backdrop, but as the main attraction. By way of bonus, Lost in NYC incorporates photos and historical facts (the field trip conceit allows a teacher character to lecture and explain); further, the book's back matter, as is typical of TOON Graphics, offers a wealth of contextual lore, social, technological, and architectural. Really, this is an overstuffed delight.

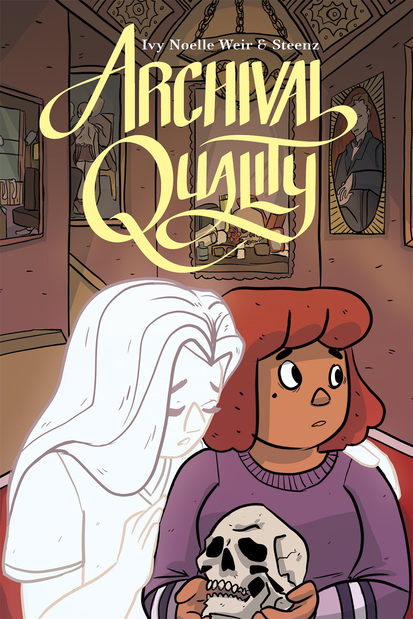

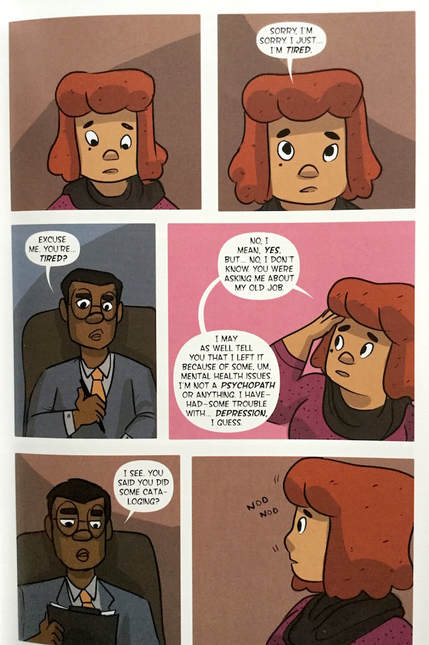

Archival Quality. Written by Ivy Noelle Weir, illustrated and colored by Steenz. Oni Press, March 2018. ISBN 978-1620104705. $19.99, 280 pages. A Junior Library Guild Selection. Archival Quality, an original graphic novel out this week, tells the story of a haunted museum: a ghost story. It also tells about living with mental illness. The protagonist Cel, a librarian struggling with anxiety and depression, takes a job as archivist of a spooky medical museum that once served as an asylum (my friend, medical archivist and comics historian Mike Rhode, should check this out). The catch: she has to live in an apartment on the premises and do her work only in the dead of night. Soon she begins to witness... happenings that she cannot explain. Her boss, the museum's curator, and her coworker, a librarian, tiptoe around her, knowing more than they will say. Cel, who lost her previous job due to a breakdown, is understandably perplexed and triggered by their evasions, and by the fact that no one seems to believe her reports of odd doings. She begins to have frightful dreams: flashbacks that evoke the shadowy history of women's mental health treatment. The plot, which like many ghost stories gestures toward the fantastic (as Todorov defined it), finally veers toward the outright marvelous as Cel investigates the case of a young woman from long ago whose presence still lingers about the place. Cel, as she works to solve that case, is by turns fragile and angry, defensive and determined—a complex character, as is the curator, at first her foil, later her ally. The story takes quite a few turns. To be honest, Archival Quality's title and look did not prepare me for its uneasy exploration of mental health treatment—or rather, the social and psychiatric construction of mental illness. As I read through the novel's first half, Steenz's drawing style struck me as too light, undetailed, and schematically cute for the story's atmosphere of updated Gothic. Cel, with her snub nose, button eyes, and moplike hair, reminded me strongly of Raggedy Ann, and in general Steen's characters have a neotenic, doll-like quality. The settings seemed too plain to conjure up mystery and dread; the staging seemed too shallow, with talking heads posed before blank fields of color or swaths of shadow, lacking particulars. Steenz favors air frames (white borders around the panels, rather than drawn borderlines) and an uncluttered look. This did not jibe with my expectations of the ghost story as a genre. But as the plot deepens, and Cel's dreams and visions overtake her, Weir and Steenz together generate suspense. The pages deal out a number of small, quiet shocks: Further, Steenz's sensitive handling of body language brings the characters, doll-like as they are, to life. The book becomes tense, involving, and, as we say, unputdownable. Weir and Steenz's back pages tell us that the two enjoyed a close working relationship, and you can tell this from the story's anxious unwinding. This is unusually strong storytelling, and a complicated, coiled plot, for a first-time graphic novel team. Clearly, Weir and Steenz are simpatico artistically—and ideologically too, I think, sharing a progressive and feminist outlook that shapes cast, character design, characterization, and plot. I will admit that not everything about Archival Quality works for me. The plot, on the level of mechanics, seems juryrigged and farfetched, that is, determined to pull characters and elements together for the sake of symbolic fitness, without the sort of realistic rigging that the novel seems to be striving for. In other words, certain things happen simply because they have to happen. Further, some elements of the story, rather big elements I think, are palmed off in the end because Weir and Steenz don't seem to be interested in working out the details. At the closing, I had the feeling that a Point was being made, rather than a novel being rounded off (to be fair, I often react this way to YA fiction, even though I know that didacticism is crucial to the genre). Still, Archival Quality, behind its coy title, offers a gutsy exploration of mental health treatment, an eerie ghost story, and characters who renegotiate their relationships with credible human frailty and charm. A most promising print debut, and a keeper.

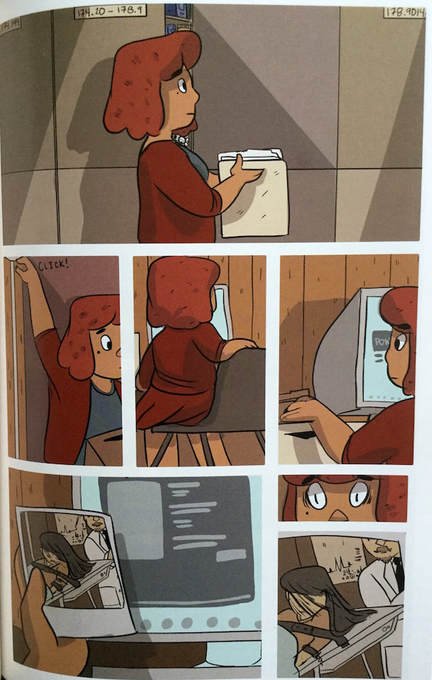

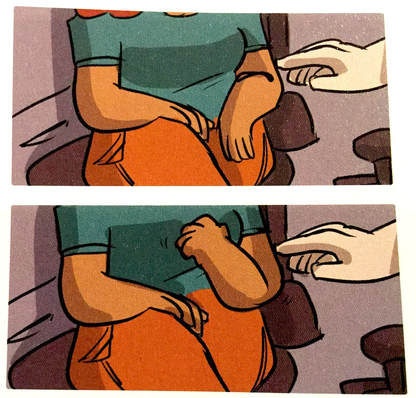

Mis(h)adra. By Iasmin Omar Ata. Gallery 13/Simon & Schuster, Oct. 2017. ISBN 978-1501162107. $25.00, 288 pages. Mis(h)adra, a sumptuous hardcover graphic novel, marks a startling print debut for cartoonist and game designer Iasmin Omar Ata, and has just been nominated for an Excellence in Graphic Literature Award (as, hmm, an Adult Book). Begun as a webcomic serial (2013-2015), its book form comes courtesy of a fairly new imprint, Gallery 13. Ata, who is Middle Eastern, Muslim, and epileptic, has described Mis(h)adra as "99.999% autobiographical" and "monthly therapy," but it's officially fiction: the story of Isaac Hammoudeh, a college student struggling to live with epilepsy, who seesaws back and forth from hope to hopelessness. The book's Arabic title, says Ata, brings together mish adra, meaning I cannot, and misadra, meaning seizure (perhaps it also echoes the word حضور, meaning presence?). Isaac desperately needs, yet cannot bring himself to accept, the help of family and friends, most particularly his new confidante Jo Esperanza (aha), who, to stay spoiler-free, I'll say faces profound challenges of her own. Mis(h)adra follows Isaac from despair and withdrawal to renewed hope, with Jo as his loving, sometimes scolding companion. The work is at once emotionally raw and aesthetically elaborate, bursting with style. While anchored in a familiar, manga-influenced look, one of simplified faces and flickering details, Mis(h)adra overflows with gusty aesthetic choices. Ata conveys the physical as well as psychological effects of epilepsy via fluorescent colors, exploded layouts, and the braiding of visual symbols: eyes, both literal and figurative, which are everywhere; strings of beads or of lights that ensnare Isaac; and floating daggers, which represent the threatening auras that warn him of oncoming seizures. The art is transporting, the seizures brutal and disorienting, yet beautiful. Tight grids give way to floating layouts. Bleeds are common, with lines sweeping off-page. Faux-benday dots, lending texture, are constant. Colors are bold and form a distinctive, non-mimetic system: pages come in pale yellow, sandstone brown, bright or dusky pink, and pure black; green and blue are used sparingly, often violently. The linework is not black but a dark purple, except on the pure-black pages, where lines of bright candy red assault the eye. Mis(h)adra renders epilepsy as a bodily and menacing experience. The story is not quite so surefooted. Only Isaac and Jo, and truthfully only Isaac, emerge as full people; almost everyone else is less a character than an indictment of normate society's insensitivity and cluelessness. The depiction of academic life is hard to credit. An explosive climax, shivering with energy and violence, gives way to an anticlimactic, fizzling resolution. Really, it seems that the book could go on and on with Isaac's struggle, but Ata simply ends because, well, a book has to stop. I felt as if the story were ending and then restarting over and over, uncertain of how to find its way. Mis(h)adra, then, is not a practiced piece of long-form writing. But it is testimony to the power of comics to create a distinct visual world, and to make a state of mind, or soul, visible on the page.

|

Archives

June 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed